From Williamsburg in New York to Shoreditch in London, artists looking for cheap premises have long been pioneers in revitalising old neighbourhoods, breathing new life into neglected areas while injecting a sense of coolness, desirability and creative energy. Around them, little businesses spring up to service their needs from coffee shops to bars and convenience stores.

However, as soon as that happens, big money eyes an opportunity for development and things start to change. Once the area becomes trendy and sought after, gentrification begins to take hold.

Property values soar, rent prices increase, and higher-income residents settle in, often at the expense of existing communities and the very same artists who led the urban renewal. The unique cultural fabric that once defined the area is gradually replaced by a more homogenised, commercialised environment.

This has happened in several other areas of London such as Brixton and Hackney. But elsewhere there are examples in city communities that tell a different story.

The east-end area of Shoreditch saw a significant transformation beginning in the early 1990s, primarily influenced by the Young British Artists (YBAs) who colonised old buildings in and round Shoreditch High Street, Hoxton Square and Redchurch Street. Initially, these artists benefited from low rents and the ability to occupy large spaces, which allowed them to create expansive, experimental works.

Combined with their innovative and often provocative art, this creative hub began to draw the attention of the art world and the media, leading to Shoreditch becoming an attractive area for creatives, which subsequently drew to it a wealthier demographic. The development of street art, trendy galleries, design studios, bars and restaurants followed throughout the 2000s.

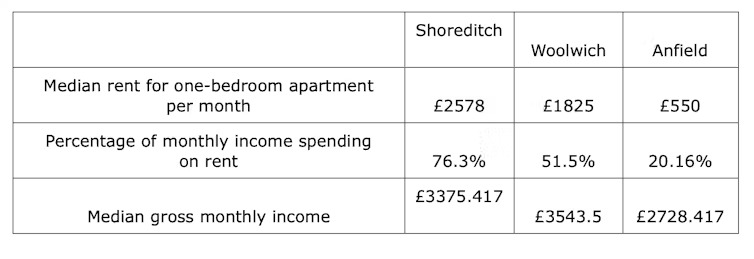

This gentrification process, while boosting the area’s economy, also meant that original artists and lower-income residents were priced out, unable to afford the rising costs associated with their own success in making the area desirable. According to data, Shoreditch residents are now renters paying more than three quarters of their income on their household (see table below) and struggling to maintain a comfortable standard of living.

Levels of affordability in Shoreditch, Woolwich and Anfield

The Index of Multiple Deprivation 2019 categorised the neighbourhood as deprived, suggesting that the area lacks community services, has low employment rates, poor health and lower educational achievements – even while parts of the economy, like real estate, are thriving.

Woolwich in south-east London has been involved since 2021 in a significant urban regeneration project instigated by cultural hub Woolwich Works. The development includes the opening of the Elizabeth Line Woolwich underground station as well as a variety of arts and performance spaces. Notable artistic companies like Punchdrunk, the Chineke! Orchestra and the National Youth Jazz Orchestra have all moved to this creative district, contributing to a new wave of cultural development.

If the data shows that Woolwich’s costs of living are still affordable in comparison to Shoreditch, some areas seem to be undergoing a similar gentrification process. For example, in the Royal Arsenal area, a portion of the redevelopment projects have pursued a high-end market, potentially putting long-standing communities at risk of being displaced.

As academics in the fields of organisational behaviour, management and real estate economics, we are undertaking a wider investigation into strategies that help preserve the integrity of cultural communities. Starting with the question, “how can arts and culture make cities that are accessible for everyone?” We are looking at how arts-led initiatives create spaces where all community members feel included and valued.

Preserving local communities

This alternative approach to arts-led urban renewal does exist, and Liverpool’s Homebaked is an encouraging example. Instigated by artist Jeanne van Heeswijk in Anfield, the project began as part of the 2010 Liverpool Biennial, where van Heeswijk, along with local residents and collaborators, initiated a transformation of a block of disused properties into a community-run bakery and housing cooperative.

The primary objective of Homebaked was to empower the local community to take control of their neighbourhood’s redevelopment. The project addressed the decline of the area which was earmarked for demolition but left in limbo.

Homebaked provided a platform for the residents to create a sustainable social enterprise and to engage in the planning of new housing and community facilities, turning a portion of the derelict site into a community hub.

While this aspect is not picked up by data – Anfield is still considered deprived – the effort put forward by the community has been noticed by the media, housing organisations and academia.

Now it is valued for what it appears to be: an urban redevelopment instigated by artists and led by locals that engages with communities and organisations to identify the aspirations and opportunities that make a difference to the people who live there.

In order to be successful, any urban regeneration has to tap into the local culture and heritage of a place. This means embracing what makes the area unique, whether it’s through traditional arts, music, local stories, or even something like baking bread.

Instead of a one-size-fits-all approach, it’s important to focus on solutions that fit a specific place, reflecting its unique identity, history and the hopes and aspirations of people who live there. Equity, inclusion and sustainability are key.

Anna De Amicis, Lecturer in Management and Media, University of Reading and Yi Wu, Lecturer in Real Estate Economics; UG Programme director, University of Reading

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.