BBC Culture emailed me in early March 2023 to ask me to participate in a poll they were holding among experts on children’s literature worldwide in order to compose a list of the top one-hundred children’s books.

Their request was to nominate our own ‘top ten’ according to particular guidelines, including the books having to be for children of 12 and under, of any genre, from anywhere in the world and chosen according to any of several possible criteria, including personal taste, enjoyment or aesthetic criteria.

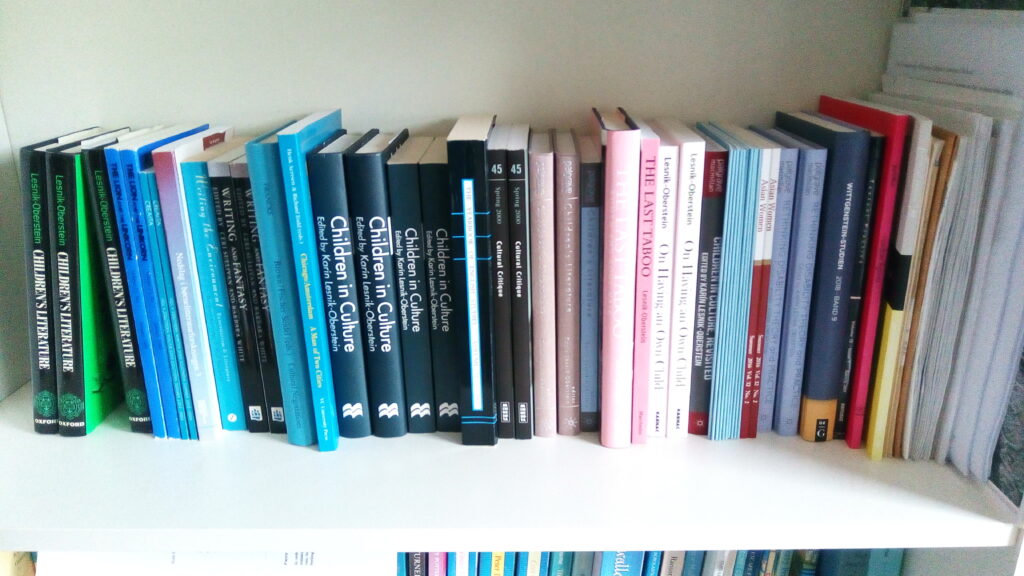

As the Director of the University of Reading’s Graduate Centre for International Research in Childhood: Literature, Culture, Media (CIRCL) and the M(Res) in Children’s Literature, choosing my top ten books raised the kind of complex and fascinating questions and issues we think about with students.

Our courses are not about what most people (both inside and outside of academia) expect: the M(Res) was founded as the MA in Children’s Literature in 1984 by the late Mr Tony Watkins and was the first master’s degree in children’s literature in the UK (and probably the world) to be accredited as a degree in English Literature instead of as a degree in Education or Library Studies, as had always been the case previously.

The CIRCL courses study children’s literature within the context of cultural studies and literary and critical theory, thinking about childhood and children’s reading as being constructed differently in different historical periods and according to different cultural, ethnic, religious, political or personal perspectives.

I chose my own ‘top ten’ based on a mix of criteria: books that are personal favourites but which are at the same time widely regarded as having cultural or historical significance, even in terms of controversy.

My top choice, Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House in the Big Woods, is regarded as one of the most famous accounts of the colonial history of the United States, but has also been viewed as racist in its portrayal and lack of portrayal of Indigenous Aboriginal peoples. But that is precisely why I wanted to include it as, in my view, its importance also lies in its being involved in such difficult but crucial discussions.

My second choice, Anne of Green Gables, has been read worldwide and has played a key role in disseminating ideas of Canadian colonial identity, gender and landscape. Mark Twain, the American author of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn famously wrote of Anne that she was ‘the dearest most moving and delightful child since the immortal Alice’.

Much less known from an Anglophone perspective is my fifth choice, Annie M.G. Schmidt’s Jip en Janneke (1953), which in The Netherlands is not only the best known children’s book (and series) but a true national cultural icon. The illustrations for the book by Fiep Westendorp remain widely used on merchandise to the present day.

Jip en Janneke can be said to be as significant on the national level as my fourth choice, Astrid Lindgren’s Pippi Longstocking, is internationally, where Pippi is widely admired as an example to free and independent women and girls everywhere.

My seventh choice, Shirley Hughes’s Dogger, is included as a tribute to the genre of the picture book, while my eighth choice, Rosemary Sutcliffe’s Eagle of the Ninth is a classic example of a historical novel for children.

My tenth choice, Mildred D. Taylor’s Roll of Thunder, Hear my Cry, is included as only one of many possible examples of classic writing about African-American culture and history.

Professor Karín Lesnik-Oberstein is Director of the Graduate Centre for International Research in Childhood: Literature, Culture, Media and the M(Res) in Children’s Literature in the Department of English Literature at the University of Reading.