Today, 7 April, is World Health Day, and this year focuses on the theme of ‘our planet, our health’. And not a moment too soon: we face an escalating crisis from climate change, food insecurity, and air and water pollution causing severe health problems worldwide.

Our national healthcare systems may be excellent in responding to health emergencies, yet they often have insufficient resources for preventative healthcare. We are continually in ‘fire-fighting’ mode, which is problematic when the fires are getting bigger and more frequent (sometimes literally). Imagine, if the NHS had a partner organisation that focused on heading off health problems at the pass, before they get more severe and costly to deal with. It could identify early warning indicators of systemic health risks and develop timely interventions to address them. Such interventions need to be transformative. For example, our intensive global food system currently produces calorie-rich but nutritionally poor food, harms biodiversity, increases the risk of zoonotic diseases emerging and produces large amounts of greenhouse gases, all of which feed back to impact our health.

This food system is influenced by the way we structure our economies, regulatory and legal systems, and even our education systems. So ‘leverage points’ for improving health involve changes to the policies and operating protocols of these systems and institutions. Equally, there is a set of ‘deeper’ interventions needed. Institutions reflect and are comprised of our collective worldviews, and so changing mindsets is necessary: what people choose to buy, how they travel, and spend their work and leisure time all either exacerbate or ameliorate (planetary) health risks. A ‘radical’ solution (from the Latin meaning getting to the ‘root’ of a problem), would be to change how we see ourselves in relation to others and the natural world. From our self-identity come values, attitudes and behavioural choices that affect our health, through long causal chains that often stretch across the entire planet.

Studies show individualistic values and practices have increased in the majority of countries over the last 50 years. Yet, when individualism is taken to excess it leads to selfish behaviour that damages the planet and, ultimately, our collective health. In contrast, when our self-identity is integrated with nature and other people, we develop more caring behaviours. Metrics assessing our sense of connection to each other and to the world around us are associated with more pro-environmental behaviours, which underpin planetary health. Incidentally, feeling connected also makes us less likely to be anxious and depressed, and so simultaneously tackling the growing mental health crisis.

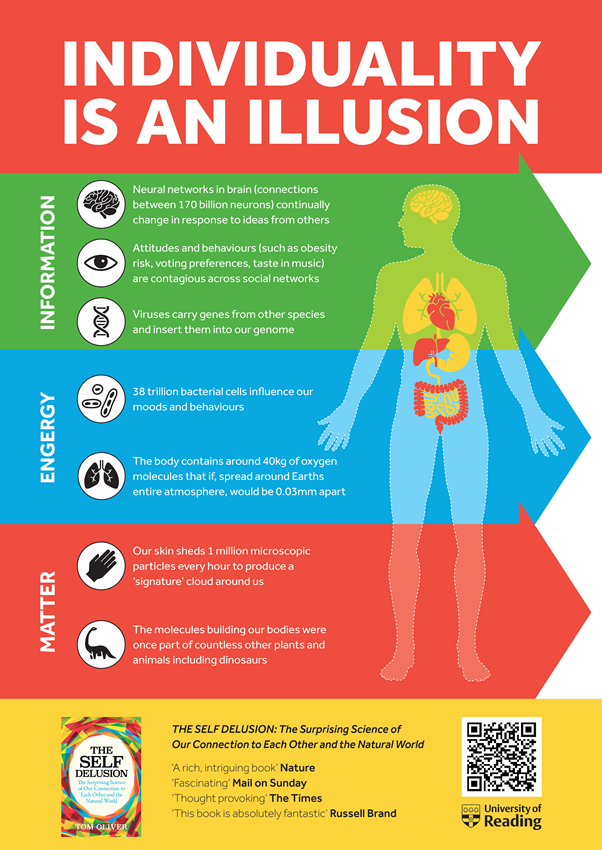

There are many ways to enhance our sense of connectedness with nature. For example, engaging in outdoor learning, painting, birdwatching, or just sitting and enjoying nature. There is also a role for deeper conceptual understanding of our connectedness to nature, which can be a motivator for engaging in nature experiences. My book The Self Delusion presented the science of how our sense of isolated individualism is a (harmful) illusion. For example, our bodies overlap with countless others and, right now, your body contains over 38 trillion bacterial cells. Bacteria live in our blood, brains, and on our skin in huge numbers (with an estimated 440 species living in between your elbow joints and around 1,000 species in your mouth). What’s more, each of our human cells contains tiny ‘organelles’ that were once free-living bacteria. The body is an open system renewing itself daily with new materials and maintaining a permeable boundary to mediate flows of energy, matter, and information. All this is directed by DNA code that is borrowed from our ancestors, and which we will pass on to ancestors to come – DNA that is composed, in very large part, of genetic code that was once part of viruses. Even our minds, which we might think define our independent identity, are influenced by every word, every touch and even subconscious pheromones (smell chemicals) from those around us.

Fiction books have been shown to influence people’s capacity for reflection and perspective-taking, but what about presenting facts like those above? A survey associated with The Self Delusion assessed people’s sense of nature connectedness, as well as their social connectedness (the sense of self-overlap with other people) both before – and after – reading the book. It reveals a significant 8.5% increase in nature connectedness, to a level much higher than previously found for adults. There was also a non-significant 8.3% increase in social connectedness. This is one small example of how we can take an evidence-based approach to developing interventions for improving planetary and personal health.

So, on World Health Day, let us feel empowered. Because, although planetary health problems ‘out there’ may feel daunting, many of the solutions actually lie within us, right now.

Tom Oliver is Professor of Applied Ecology and author of The Self Delusion.