While most of us were tucking into our Christmas dinners, Dr Sakthi Vaiyapuri was travelling around southern India teaching people how to avoid being bitten by venomous snakes. He talked Sarah Harrop through pictures from his trip, what he achieved – and the snakebite diagnostic test he’s developing here in his Reading lab which he hopes will save many more lives.

Each year, snakebites kill around 150,000 people, mostly those living in rural communities. University of Reading pharmacologist Dr Sakthi Vaiyapuri – who was born in Tamil Nadu and has seen the effects of snakebite first-hand – is on a one-man mission to change that.

Quick diagnosis saves lives

Sakthi’s research concerns platelets, the part of our blood responsible for clotting, and one aspect of his work is studying the effects of snake venom on this process.

Alongside working on potential new treatments for snakebite in the lab, Sakthi is supervising the development of a diagnostic kit by his PhD student, Harry Williams. It’s a simple antibody test strip similar to a pregnancy test, which can quickly determine the type of snake that has bitten a person from a drop of their blood or urine. In practice, this would allow a bitten person to receive the correct treatment as quickly as possible.

“Snakebite is currently treated based on the symptoms – there is no diagnostic kit available. People working in primary healthcare centres who see snakebite victims often don’t have the confidence to treat them, so they send them to the big hospitals and the patient will often die on the way there,” explains Sakthi.

The test the team are developing first reveals whether or not there was venom in the snakebite. Secondly it shows which type of snake bit the person and therefore how to treat it. A bite from a cobra, for example, needs radically different treatment that from a viper. Sakthi hopes that the cheap-to-produce kits could ultimately be kept in local pharmacies.

“We want to save anti-snake venom (ASV) treatment only for treating venomous snakebites so that we don’t waste precious ASV unnecessarily. There’s currently a huge shortage,” Sakthi explains.

Spreading the word

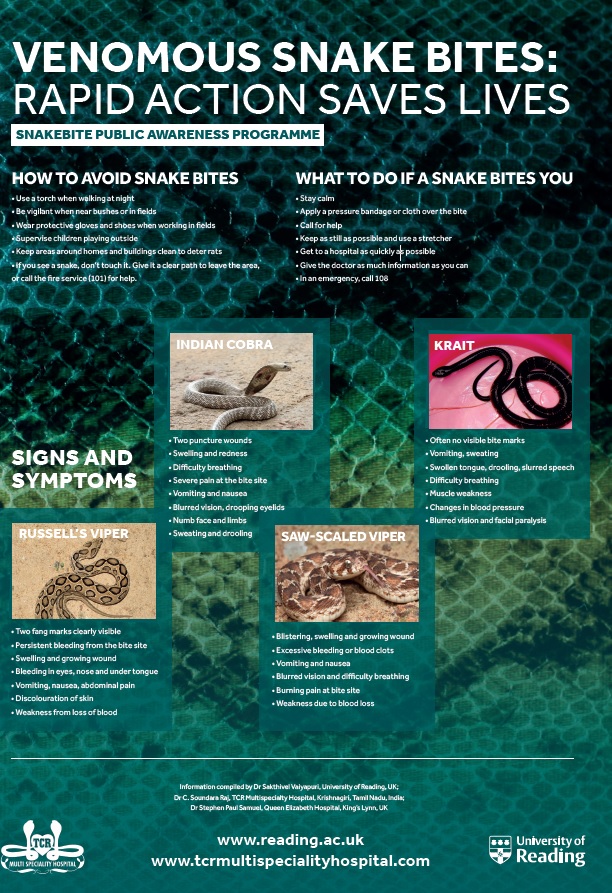

As if the research is not keeping him busy enough, in the short term Sakthi has developed a public awareness leaflet and film about how to avoid snakebite, which species are venomous and which are not, and what to do if bitten.

With Dr Stephen Paul Samuel from the Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Kings Lynn and snakebite specialist Dr C Soundara Raj from Tamil Nadu’s main hospital, he’s been taking his public awareness campaign around schools, colleges and rural villages. Armed with boxes of leaflets, a laptop and a folding cinema screen, the team toured police stations, markets, schools, libraries, farms, railway and bus stations and temples, spreading the word to anyone who would listen.

“We’re trying to break down three common misconceptions or barriers,” says Sakthi. “Firstly, the mistaken belief that using a tourniquet is the best way to treat snakebite, secondly that traditional healers can treat all types of snakebite (they can’t), and thirdly we are addressing the lack of knowledge about which species of snake are venomous by telling people which ones to look out for.”

Tourniquets can be harmful because if incorrectly used they can completely cut off blood circulation. It can often take three hours or more before a victim in a remote location reaches the hospital, by which point the limb has been so long deprived of oxygen that it has to be amputated. “We tell people not to do that unless they know how to apply a tourniquet. You need to limit blood flow away from the bite site by around 50%, not completely stop it,” he explains.

Encouraging people to go to hospital rather than visiting traditional healers is another simple way to save lives. “We educate people that they should go to hospital and that going to healers is a complete waste of time. There are a lot of false beliefs around snakes – for example that lime stones will cure snakebite symptoms or that a rat snake will bite through its own tail, which is something I believed myself as a child.”

Prevention is better than cure

Perhaps most importantly, Sakthi and colleagues have been teaching people how to recognise the ‘big four’ venomous snakes – the Russell’s viper, Indian Cobra, Saw-Scaled Viper and Krait – to avoid being bitten in the first place. People often have little, if any, knowledge of which species to avoid and how to spot them. And some venomous species can look similar to harmless ones. For example, one snakebite victim the team spoke to had caught a deadly Russell’s Viper with his bare hands, mistakenly thinking it was a python.

The team’s 18-day road trip took in 19 schools and colleges, 26 villages and towns, and 4,000 km. They reached an estimated 40,000 people with the campaign. The presentations were attended by all students at each institution – or as many as could be packed into a hall. At the end of each visit there was a Q&A session, with Sakthi and local snakebite specialist Dr C Soundara Raj on hand to answer all types of question – from the mythical to the medical.

Locals reading the leaflets.

Locals reading the leaflets.

Monitoring success

So what does Sakthi plan to do next? Leaflets will continue to be delivered until the end of March 2019 until 100,000 have been distributed. A pilot trial is being run from the TCR Multispecialty Hospital – the main hospital serving the villages that the team have targeted. It is gathering data on how many snakebite victims who come to the hospital have done so as a result of seeing the public awareness video or leaflet.

Ultimately, Sakthi has big ambitions for the work: he’d like to see the public awareness campaign rolled out nationally, and free treatment for snakebite to be available throughout India. In parallel, he is seeking funding to develop his diagnostic test kit.

Back at the lab bench here at Reading, he’s continuing to work on small-molecule drug candidates to treat the effects of snakebite. Unlike anti-snake venom, such drugs could be made available in tablet form and would not have to be stored in the fridge, which opens up the possibility of making treatments available to everyone, even in the most remote places.

Dr Sakthi Vaiyapuri is an Associate Professor within the University of Reading’s School of Pharmacy

Learn more about the impact of Sakthi’s work in our research highlight about the project

Find out more about Sakthi’s research career at Reading in this 2012 interview