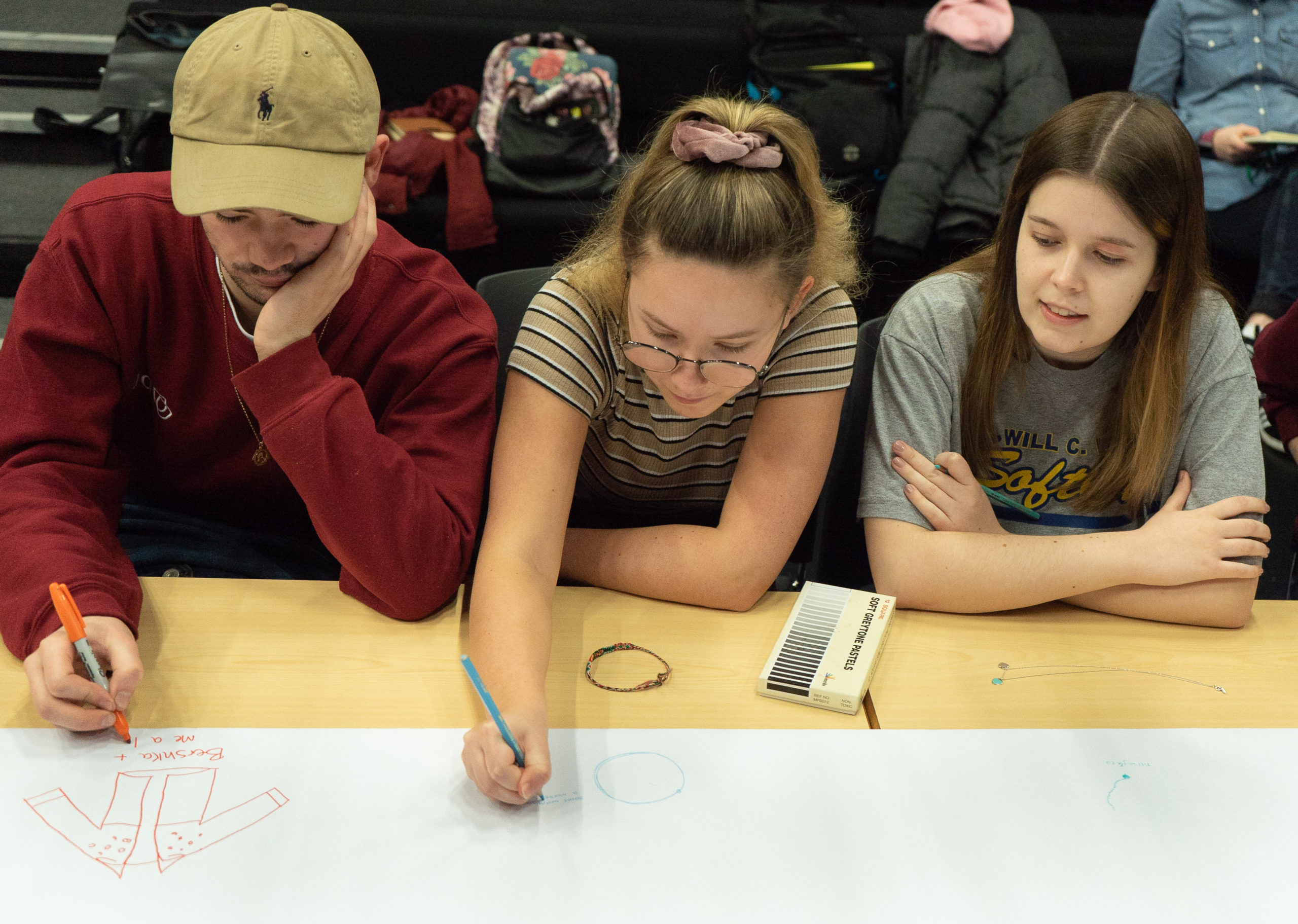

On 5th February 2020, students from the Department of Film and Theatre attended a workshop led by Sheila Ghelani and Sue Palmer, following a performance of Common Salt.

Here, Alice Underwood, who graduated from the BA in Film and Theatre and MA in Creative Enterprise at the Department for Film, Theatre and Television, writes about her experience of the workshop:

Punctuated with questions to probe our own relationship with ‘post’-colonialism

starting with their left hand on the maze, they turn left seven times, with each turn showing the deeper roots of the apparently vanishing hedgerow of India. Common Salt exposes the deliberate gaps placed in the modern knowledge, ‘the books with their missing knowledge’.

Being welcomed into a space has never felt as true a statement as we took our seats in a seminar room nestled in the Museum of English Rural Life, greeted and made comfortable by Sheila Ghelani and Sue Palmer. Waiting until their audience was ready, it almost felt like the two performers were following our lead before they took us on a journey across the world via the meticulously chosen props on their table. A museum, the most fitting of venues for this intimate and ostensibly gentle show and tell, delving into the brutality and hidden history of the East India Trading Company and wider aftershocks of British Colonialism. We were taken from Hedgerows to hedge funds as it was explained how the legacy of the East India Trading Company still weaves its way into our everyday lives. This harsh reality made inescapable as the drone from the Shruti box punctuated each section. A lament could not be more appropriate as the two women sing about what was lost for imperialism’s gain.

By beginning their research at Hampton Court, the famous hedgerow maze made for the perfect theatrical metaphor. Each turn made with your left hand always touching the wall, the ever present reminder of the irreparable damage the British Empire has inflicted beyond what our modern lives can comprehend. With each turn, an unexpected link to how the natural world shaped and exploited by colonialism. The objects of nature always present on the table and in the room, named and used to illustrate striking connections with the contemporary world and how it, like the hedge maze, has been pruned to be as superficially impressive as possible. One of the most striking images stays with me. A whole container of common table salt, the very one that sits in my kitchen worktop being poured onto the table over some delicately scales made from precious metal. The jarring aesthetics of the luxury to something as common as salt showing how the many people of India were starved as the East India Company paved our city streets with stolen gold.

I still consider, some months later, the final section of the piece. The performer earnestly ask questions about their journey and what they have learned and discussed. Yearning to hear what the other thinks, as an audience member I felt somewhat intrusive on this moment between the two of them as they ask

‘Is the sea haunted?’

‘yes’

‘Do you still swim in it?’

‘… yes’

To me, this question can have a multitude of meaning. But what really resonates is how engrained our colonialist past is in our lives, that even once exposed to the enduring horrors we still swim in the sea.

.