by Mark McKerracher, Abhishek Dutta, Megan Gooch, Helena Hamerow, Horace Lee, Michael Lewis and Andrew Zisserman

The British Museum holds millions of objects spanning millennia of human history. But it also curates a unique and precious resource that is purely digital and freely accessible online: the database of the Portable Antiquities Scheme, which contains records of more than 1.5 million artefacts – primarily those discovered by metal detecting enthusiasts.

Metal detecting – as lovingly mocked in the BBC sitcom Detectorists – is a hugely popular pastime in the UK. There are some 20,000 metal-detectorists regularly discovering things like coins and dress accessories, from various periods of British history and prehistory, in ploughed fields across the country.

From its inception in 1997, the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) has been encouraging detectorists in England and Wales to report their finds for recording in a central database (maintained by the British Museum in partnership with Amgueddfa Cymru) so that the unique informative potential of these artefacts can be fully realised – both in professional and academic research and by amateur enthusiasts. Photographs and metadata are collected and entered into the database by both expert professionals – a national network of 40 locally-based Finds Liaison Officers, supported by National Advisers – and also trained volunteers and interns.

This data entry is no mean feat, considering the vast array of object types – from any and all periods of British history and prehistory – that fall within the purview of the PAS. From golden Bronze Age cups to Victorian pennies, from Roman rings to early medieval strap ends, it is unrealistic and unfair to expect any individual to acquire the detailed expertise needed to accurately identify all conceivable finds, let alone to describe them in consistent specialist language, and to apply ever-more-detailed classifications and sub-classifications. This difficulty will only grow as the monumental PAS dataset grows every year; and the increasing potential for inaccuracies or inconsistencies could make it harder for the archaeological community to use the PAS as a research resource.

An assistive AI tool which can ‘look at’ a photograph of a new artefact and find visually similar items for comparison (and perhaps even suggest pre-populated metadata) could therefore be a boon for the PAS network and its users – both metal-detecting enthusiasts and professional archaeologists – by improving the efficiency, efficacy and accuracy of data entry, and by enhancing the research utility of the database.

The AntiquAI project, a collaboration between the University of Oxford and the Portable Antiquities Scheme, aims to create such a tool: harnessing the latest developments in image-recognition technology and applying them to the PAS dataset.

AntiquAI is currently in a pilot, proof-of-concept phase, exploring the potential of PAS image recognition. The Visual Geometry Group (VGG) in Oxford’s Department of Engineering Science – research leaders in the field of computer vision – are developing the project’s software. Among the software currently under development by the VGG is WISE: an open-source image search engine, drawing upon recent advances in vision-language models to enable flexible searching of image content using natural language, and/or visual search terms (i.e. new images).

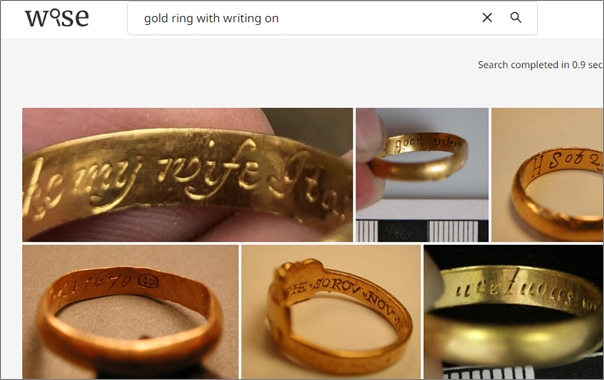

The VGG have created an instance of WISE indexed on a very large, representative subset of PAS images and metadata, representing over 700,000 objects (thanks to Stephen Moon at the British Museum for sharing this invaluable resource). This prototype now allows us to successfully search PAS records – with or without reference to object metadata – using natural language terms, such as ‘gold ring with writing on’.

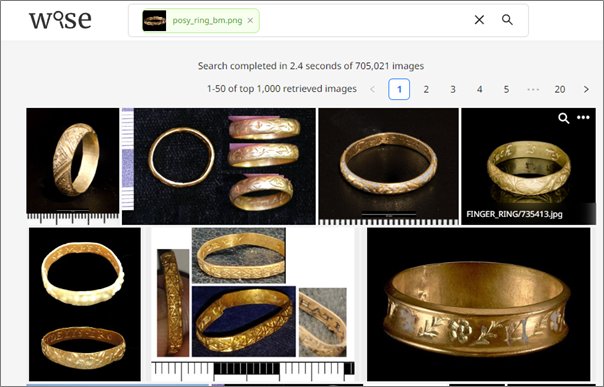

AntiquAI’s instance of WISE can also take an image as a search term. Here, for instance, we have used a photograph of a medieval posy ring (downloaded from the British Museum website, and previously unseen by WISE) as a search term, and WISE has found visually similar objects.

So far, WISE’s understanding of natural language terms is largely generic, trained on non-specialist image-word pairings gleaned from the web. As a result, it cannot necessarily ‘speak archaeology’. It understands what a gold ring is, for example, but struggles with an anthropomorphic medieval strap end. The VGG is now working on training WISE to understand specialist archaeological terms. If successful, we shall be a significant step closer to achieving AntiquAI’s ultimate goal: the AI-assisted classification of metal-detector finds.

With thanks to the Finds Liaison Officers, volunteers and all staff and contributors to the PAS, without whom the AntiquAI project would be impossible.