by Sophie Whittle, Digital Humanities Institute, University of Sheffield

Introduction

In June, I had the pleasure of attending the inaugural DH and AI conference at Reading. Since then, I have been reflecting on AI’s implications for higher education, as well as wider communities.

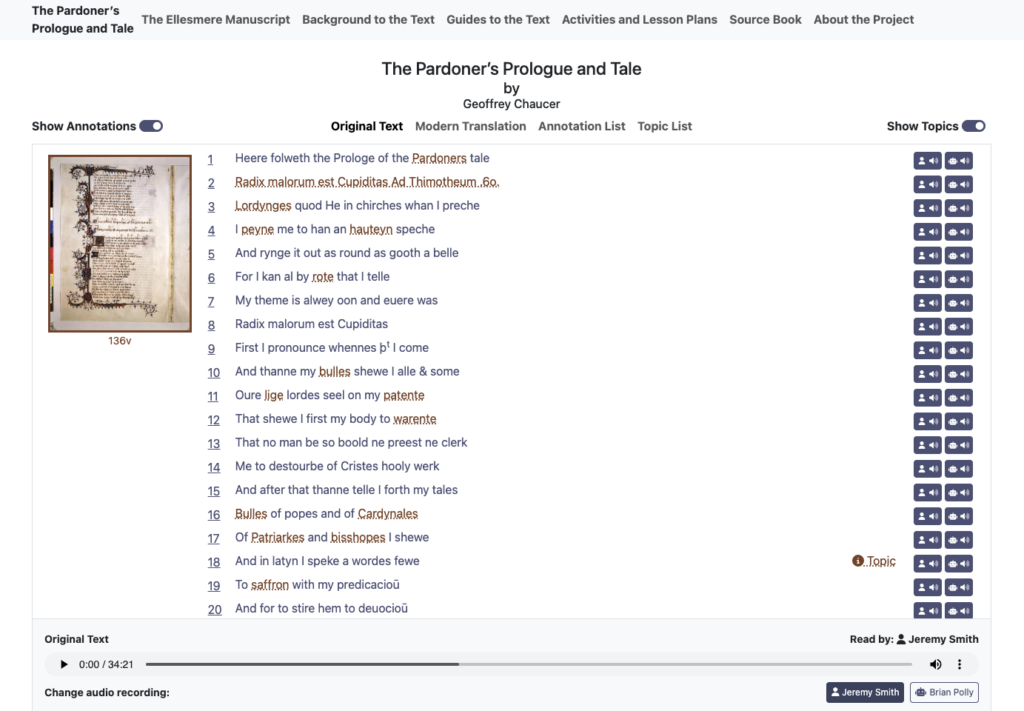

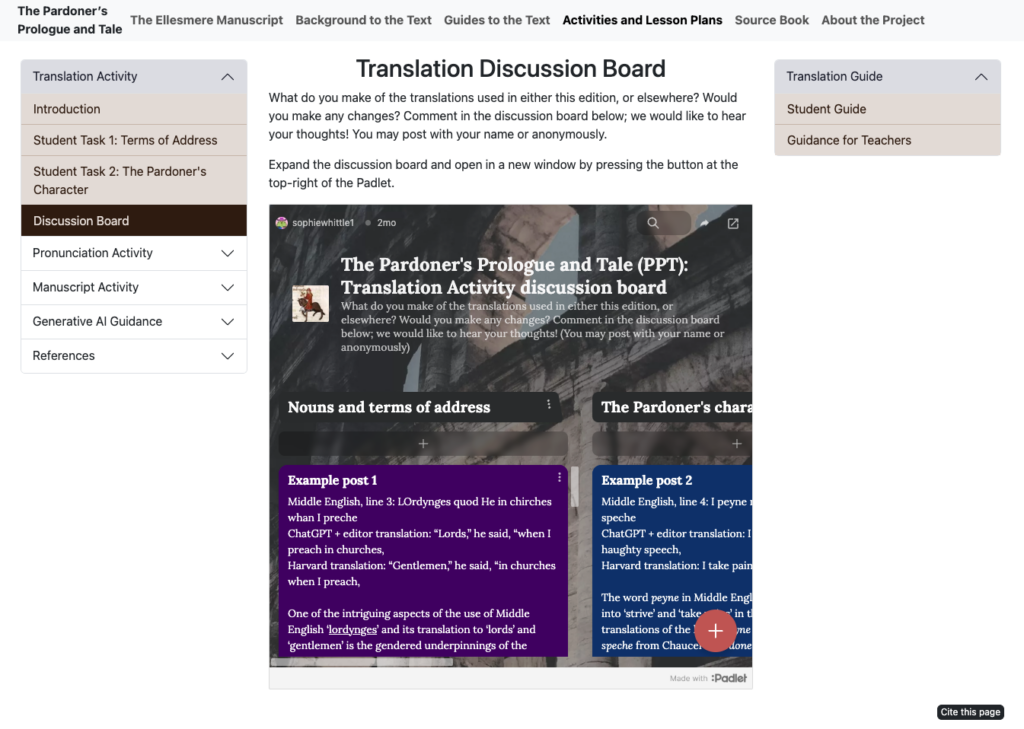

I began investigating Large Language Models (LLMs) as part of the C21 Editions team, including AI’s ability to produce a prototype digital teaching edition of Chaucer.[1] The initial aim of the project sought to explore the capabilities of machine-assisted technology more broadly, merging the curatorial and statistical aspects of historical editing.[2]

From 2023 onwards, we wanted to gauge whether LLMs could reliably interpret historical textual traditions and produce engaging digital teaching resources. The aim was to maintain traditional aspects of editing, including diplomatic transcriptions, detailed annotation of the text and essays on scholarly interpretations, while improving the efficiency of the editorial process and meeting students’ expectations of interactivity.

Why Chaucer and The Pardoner’s Prologue & Tale?

Geoffrey Chaucer, the author of the 14th Century text, The Canterbury Tales, was named ‘the father of English poetry’ by John Dryden in 1700. Yet, recent criticism of Chaucer suggests his texts promote hegemony via upholding white, patriarchal values (e.g. see recent evidence about Chaucer’s lawsuit, which initially prompted discussion about possible sexual assault).

Sarah Baechle and Carissa Harris make the interesting point that the ethical questions raised by Chaucer’s inclusion on the university curriculum lead to a deeper critique of historical attitudes to consent, race, and societal binaries and categories.[3] Ruth Evans also draws attention to expanding and shifting conversation within Chaucer studies, through modern criticism, adaptation, and reparation.[4] For instance, Chaucer’s Wife of Bath has been adapted for the stage through Zadie Smith’s Jamaican-born and British Wife of Willesden.

The fluidity of the Pardoner’s desires has sparked interest in his representation of medieval queerness, despite strict Catholic opinion against ‘sodomy’.[5] Students and teachers in our focus groups frequently stated that learning about Chaucer and his texts led to further research on global medieval literature, racism in the Middle Ages, and gender and sexuality as a spectrum. How, then, does AI fare when prompting its interpretation of medieval texts, in ways that address the history of Chaucer’s reception?

Benefits and Limitations of AI for Interpreting Chaucer’s Texts

LLMs such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT could only provide surface level summarisation and description, as might be expected given the age of medieval literature. Without significant editorial intervention, and additional guidance from open access data such as Wikipedia, outputs were sparse and the overall process of prompting sufficient responses slow. Below is a recent example output from the prompt, ‘Summarise the theme of gender and sexuality, as well as gender fluidity, queerness, and masculinity, in Chaucer’s Pardoner’s Prologue and Tale, to a university level standard with references.’

2. Gender Fluidity and Queerness

The Pardoner’s self-presentation and ambiguous identity play with ideas of gender fluidity and queerness. Throughout his prologue, the Pardoner appears to relish his liminal status, and his description, behavior, and performance can be seen as a critique of the rigid gender roles of his time. As an individual who occupies a space between established categories of male and female, the Pardoner embodies a form of gender fluidity that resists traditional binaries.

Moreover, the Pardoner’s association with relics and his role as a religious figure allow him to blur the lines between the sacred and the profane. His very profession involves deception and manipulation, which parallels his fluidity of identity. This sense of indeterminacy is further emphasized by his admission of deceit in selling indulgences: he is a performer who knows how to manipulate appearances to his advantage, much like how he manipulates his own identity.

The Pardoner’s queerness can also be seen in his relationships with other pilgrims. His close association with the Summoner, another morally ambiguous figure in the Tales, has led some critics to suggest a homoerotic subtext. The Pardoner’s own words at the end of his prologue – inviting the pilgrims to kiss his relics or the “bones” – carry a sense of homoerotic double entendre (Rigby, The Pardoner’s Tale and Gendered Power).

3. Masculinity

The Pardoner’s character also interrogates medieval constructions of masculinity. In his ambiguous gender presentation and his rejection of traditional masculine roles, he becomes a figure who challenges the conventional ideal of the male Christian pilgrim. The Pardoner’s narrative voice in his prologue is marked by a conscious subversion of these ideals: he mocks the idea of piety and openly confesses to exploiting the gullibility of his audience for personal gain.

Furthermore, his tale, which is a moral narrative about three rioters who meet their end due to their greed, can be read as a commentary on masculine excess. The rioters represent unchecked masculine aggression, gluttony, and a pursuit of power – vices that lead to their destruction. In this sense, the Pardoner’s tale becomes a critique of the very ideals of masculinity that he himself eschews.

References:

-

- Chaucer, Geoffrey. The Canterbury Tales. Edited by Jill Mann, Penguin Books, 2005.

- Dinshaw, Carolyn. Getting Medieval: Sexualities and Communities, Pre- and Postmodern. Duke University Press, 1999.

- Rigby, Stephen H. “The Pardoner’s Tale and Gendered Power.” Chaucer and Gender, ed. Elaine Tuttle Hansen, Oxford University Press, 1992.

Extracts of the output from the publicly available ChatGPT-4o, on the gender and sexuality of the Pardoner (28 August 2024).

Interestingly, the response draws on recent notions within queer theory, explaining that the Pardoner’s desires challenge ‘rigid gender norms’ of medieval society, with his perceived ‘sinful’ actions at odds with church beliefs. However, there are several issues with the output, as it 1) refers to an irrelevant relationship with the Summoner pilgrim (it does not feature in The Pardoner’s Tale); 2) does not acknowledge the Pardoner’s tension with the Host, crucially reflecting hypermasculinity; and 3) the few references were published not later than 2005. There is also little accuracy in the referencing of these sources – for instance, Hansen’s book is actually named Chaucer and the Fictions of Gender (within which Rigby’s work does not feature), and an entire edition of The Canterbury Tales is used as secondary research, without clearly stated page numbers. Lastly, the output sentence, ‘His very profession involves deception and manipulation, which parallels his fluidity of identity’ does not provide the required amount of nuance about medieval sin and society, which appears in recent academic scholarship. There must be more analysis of the perception of ‘sin’ and ‘deviance’ in medieval society as deception and manipulation, which, to a modern reader, might be more concretely associated with his selling of false relics. From the output, a user might assume that the LLM is associating queerness and fluidity with ‘sin’ as a contemporary perspective, rather than specifying that this is a historical perception. There is a lot of recent scholarship celebrating the Pardoner’s queer identity, his ability to outsmart the other pilgrims and his audiences, and the reclamation of power when he challenges the Host, which is not evident from the output. These contemporary themes attract students’ attention today, and these linguistic nuances have real implications for their learning of the medieval period.

What are the Implications for Teaching and Beyond?

As institutions are beginning to communicate, GenAI outputs must be unravelled further by students. In particular, AI use must be paired with knowledge from well-informed teachers, alongside authoritative secondary research. These outputs may be suitable for overviews of medieval tales, but they must be investigated for their suitability and trustworthiness. Baechle and Harris also suggest that, to avoid ‘deifying’ popular medieval writers such as Chaucer, students must be equipped to interrogate historical attitudes.[6] The same goes for examining Chaucer’s literature through AI tools.

The screenshots above present our current prototype. Alongside interactive aspects, we have included activities and discussion boards for further interrogation of, and collaboration on, Chaucer’s works and the AI technology used in the edition. These activities are crucial for embedding critical perspectives of AI into learning, which must occur alongside guidance of its implications on society more widely.[7]

I end this post with some of these societal implications. As Bender et al. note, these models often encode hegemonic views, resulting in outputs that have the potential for misuse by society.[8] The anthropomorphism of AI – the images of humanoid AI robots completing everyday tasks, like the image of ‘AI Chaucer’ above – leads to the belief that LLMs have the capacity for human ‘intelligence’. The creation of departmental resources to improve critical AI literacy, such as Rutgers’ AI Council living document, equips teachers with the practical and ethical implications so they can make informed decisions about its risks. It is these approaches that must be embedded into university learning of all disciplines, particularly for engaging and sparking interest in Chaucer studies.

[1] The C21 Editions project was generously funded by UKRI-AHRC and the Irish Research Council under the UK- Ireland Collaboration in the Digital Humanities Research Grants (grant numbers AH/ W001489/1 and IRC/W001489/1). The collaboration is between the Digital Humanities Institute (University of Sheffield), the University of Glasgow, and the Department of Digital Humanities at University College Cork.

[2] Katherine Bode’s discussion on bridging the curatorial and statistical aspects of DH studies can be found at: https://critinq.wordpress.com/2019/04/02/computational-literary-studies-participant-forum-responses-day-2-3/

[3] See: Baechle, Sarah, and Carissa M. Harris. ‘The Ethical Challenge of Chaucerian Scholarship in the Twenty-First Century’. The Chaucer Review 56, no. 4 (2021): 311–21.

[4] See: Evans, Ruth. ‘On Not Being Chaucer’. Studies in the Age of Chaucer 44, no. 1 (2022): 2–26.

[5] See: Dhouib, Mohamed Karim. ‘De/Stabilizing Heterosexuality in the Pardoner’s Tale’. International Journal of Language and Literary Studies 3, no. 4 (5 December 2021): 154–66.

[6] Baechle, Sarah, and Carissa M. Harris. ‘The Ethical Challenge of Chaucerian Scholarship in the Twenty-First Century’. The Chaucer Review 56, no. 4 (2021), p. 318.

[7] A more in-depth analysis of AI in pedagogical contexts can be found on ‘The AI Hype Wall of Shame’, by Katie Conrad and Lauren M. E. Goodlad.

[8] Bender, Emily M. et al. ‘On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big? 🦜’. In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, p. 616.