Dr Amy Richardson

On this blog in December, Mara Oliva raised the significant problem of “digital disparity”. In this blog, I want to revisit this issue, which is significant in Iraq where 59% of young people lack the digital skills required for employment. This gap is even more significant for women, only 51% of whom have access to internet, compared with 98% of men in Iraq. Over the past decade, we have been working with our colleagues in Iraq to address the gap in digital provision, through capacity building and amplifying voices in digital heritage.

Since the invasion of 2003, we have seen regular stories in the news about the looting of the Iraq Museum and the increased black-market in antiquities. The damage to Iraq’s heritage was compounded by the actions of ISIS in 2014, whose deliberate destruction of cultural heritage sites was an attack on the cultural rights of communities. In response to these acts, the international heritage community rallied to find digital approaches that could mitigate some of the damage through digital reconstructions and 3D printing of lost monuments. Reflecting on the state of heritage in Iraq in the post-conflict period, priorities have now shifted towards investment in infrastructure and skills-training to support and strengthen Iraq’s heritage sector, particularly through Iraqi-led projects and support for cultural heritage protection measures.

In the long term, conflict is only one of the risks threatening the future of Iraq’s more than 17,000 heritage sites. Climate change, development and neglect all have a detrimental impact on cultural and natural heritage. At present, three of Iraq’s six UNESCO World Heritage sites have been included on the List of World Heritage in Danger. Together with Roger Matthews and Wendy Matthews in Archaeology at the University of Reading, I have been working with project partners in Iraq to develop resources for Heritage and Eco-tourism for Sustainable Development in Iraqi Kurdistan. In a recent survey on heritage in Iraqi Kurdistan, stakeholders noted current barriers in access to information about local heritage. To tackle this disparity, we are co-creating heritage guides in English, Arabic and Kurdish, available as both physical and digital resources, to ensure free and fair access to knowledge in the region. In partnership with the Slemani Museum, the Directorate for Antiquities and Heritage Sulaimaniyah, and Dr Rozhen Kamal Mohammed-Amin from the Cultural Heritage Organization, we have been developing augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) experiences to encourage sustainable engagement with the rich cultural and natural heritage of the region. Rozhen and her team have been at the forefront of AR and VR development in Iraq, working with minority rights groups to develop apps and VR experiences to develop empathy and understanding of the experiences of the persecuted Yazidi ethnic minority who were subjected to war crimes.

Knowledge exchange in digital heritage forms a core part of our projects. In recent years, there have been increasing calls on archaeological teams to prioritise building in training for Iraqi counterparts in the heritage sector. We have been working with colleagues in Iraq and Iran building capacity in digital skills, including training in digital recording techniques for the MENTICA project (such as databases, GIS, photogrammetry) and in new technologies for heritage protection, building gender balance into all our initiatives. We have committed to Open Access publishing our research, working with the Archaeology Data Service to ensure FAIR data principles are embedded in our practice, releasing both our results and the underlying data.

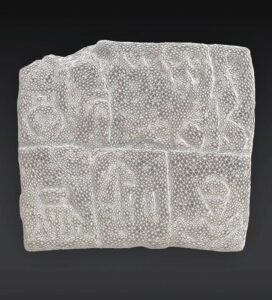

Open Research approaches are embedded in a new project, starting February 2023. Working with colleagues in the Vorderasiatisches Museum, Roger Matthews and I are examining the origins of bureaucracy. This project applies digital humanities and scientific approaches to clay objects involved in the administration of the first cities in Mesopotamia between 3,700 and 2,700 BC, including some of the earliest written documents in the world. Digital imaging of objects can reveal traces of the people who shaped the clay, such as the fingerprints of the men, women and children worked together to organise communities in the ancient world. Through network analysis, we are exploring the connections that people made and how they collaborated to shape society. The results of the project will form the basis of an online exhibition in 2026, as well as an Open Access database. This project aims to improve digital access to museum collections and unite fragmented collections, where the material from sites in Iraq has been distributed between different museums, and indeed different countries.

Through sustained collaboration at every level, digital disparity in Iraq is narrowing. International and governmental initiatives are developing strategies for the digital landscape of Iraq. NGOs and makerspaces are providing support for startups, delivering training in IT skills and business management. Organisations such as 51 Labs and the Cultural Heritage Organization are embedding social responsibility at the heart of their mission to foster grass roots opportunities. People in Iraq are building a new digital future for themselves and it is one deeply embedded in heritage, sustainability and new technology.

Amy Richardson is a Senior Research Fellow in Archaeology. Her work is supported by the European Research Council (MENTICA: grant no. 797264) and the Arts and Humanities Research Council (HESDIK: grant no. AH/W006790/1; States of Clay: grant no.AH/X001717/1). Amy is a University of Reading Open Research Champion.

In my role as

In my role as