The AHRC-funded project ‘The Legacy of Stephen Dwoskin’s Personal Cinema’ discovered novel uses of digital forensics, data exploration and visual analysis to advance archival and creative practice, and humanities research, as well as research data management.

The project centred on Dwoskin’s archive, held at the University of Reading. As well as personal papers, documents, magazines, photographs, his graphic design and letters, it included 22 hard drives which held a vast amount of unedited and edited audiovisual material (video files), as well as images from Dwoskin’s work as a graphic designer, emails and other files. The survey of this archive presented huge technical, archival and ethical challenges.

Researchers from the University of Reading’s Department of Art worked alongside specialists in digital forensics and data visualisation to extract the files, see what a data-driven overview could tell us about the creative process, and use the archive as a whole as a litmus test for ethical procedures with artists’ personal material. The team’s work in digital archiving was recognised when they were finalists in the Digital Preservation Coalition Awards 2022.

Read more to discover the project’s pioneering approaches in:

- data exploration to reveal clues about an artist’s personal/professional history, stages of creative processes, and technical environment

- visualisation of the file directory structure and timeline, as a supplementary tool for archival processes in description and management

- visualisation of Dwoskin’s email inbox to address the conflict between privacy and access, as well as privacy conscious data management and its impact for humanities research

- novel methods of analysis of Dwoskin’s use of sound and video shots, including visualisations, movie barcodes and audio spectrograms

- Dwoskin: the man and the material

- Dwoskin’s cinematic historiography

- Opening up the box: digital forensics and data exploration

- Collaboration as innovation

- Project team

- Bibliography

Please note: This article contains discussion of physical disability, of objectification of disability, and of material with strong sexual and pornographic themes.

Dwoskin: the man and the material

Stephen Dwoskin (1939-2012) was an experimental filmmaker who contributed significantly to the underground film community in his native New York and later in London, where he settled for most of his life. Dwoskin contracted polio as a child, leaving him without the use of his legs, which as an adult necessitated him being an early adopter of digital technology for capturing and editing film. A contemporary of Andy Warhol and Derek Jarman, his proudly intransigent adherence to an idiosyncratic style of filmmaking combined with ‘wrong place, wrong time’ meant that Dwoskin was forever on the periphery of the fame that they enjoyed. He supported himself through a successful career as a graphic designer, through teaching at the London College of Communication and later Professor of film at the Royal College of Art, and through commissions for television channels in the 1970s.

When Dwoskin died he left a four-storey house filled with decades of material from his life as an artist, including traditional paper diaries and correspondence, as well as 22 hard drives containing extensive email exchanges, collages, and film files in various stages of editing. This material came into the archives of the University of Reading through the efforts of Rachel Garfield – a personal friend of Dwoskin, one of his executors, and then Professor of Fine Art at the University – and soon became the subject of a 3-year AHRC-funded project, ‘The Legacies of Stephen Dwoskin’s Personal Cinema’ (2018-2021), with Rachel as PI.

The team’s aim was to reassert Dwoskin’s place in his various historical contexts, and to use his archive as a case study for the potential of digital analysis on such a complex archive, informed by more art-historical and theoretical approaches. The new analyses produced by pioneering approaches in digital forensics and data visualisation would be given meaning in the context of Dwoskin’s life through traditional close readings. In the process, the physical form in which Dwoskin’s archive was preserved loomed large, providing a huge opportunity for upskilling archivists here at the University Museums, Archives & Special Collections Services (UMASCS).

The complexity of the material and the combination of four types of stakeholder – researchers in film and art, creative practitioners, archivists, international distributors and preservers of the films such as the BFI and the LUX, and data managers – made this project a unique opportunity for new thinking on curation and preservation.

Dwoskin’s cinematic historiography

An overriding theme in Dwoskin’s work is the relationship between the filmmaker and the subject. Most of his films are studies of women and desire, with the protagonists usually played by Dwoskin’s own friends or mutual friends, who were often important artists in their own right such as Carolee Schneemann and Cosey Fanny Tutti. In a typical example of one of his early New York underground films, a woman would smoke a cigarette on Dwoskin’s own bed for ten minutes. Having been taught to dance as a child, Dwoskin remained fascinated by artful movement, and preferred to work with dancers even when they would not be required to move beyond one location, in which they engaged in silent exchanges with the lens.

Laura Mulvey, film theorist whose article ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ helped bring the term ‘male gaze’ (coined by John Berger to describe European art) into the vernacular of film studies, was a friend of Dwoskin. His films were hugely influential on her thinking: an early draft of her article in fact included a discussion of his work. Interviews with the women in Dwoskin’s films suggest that the atmosphere was comfortable for them and they were active participants in the creative process; Dwoskin’s autobiographical film Trying to Kiss the Moon features footage of one long-standing collaborator, Beatrice ‘Trixie’ Cordua, watching an earlier film of herself when she was younger. Nonetheless, as these films are dominated by an esoteric voyeurism, they are bemusing or even uncomfortable for outsiders to watch. This was partly the point – Dwoskin wanted the viewers to feel the discomfort of the camera’s gaze on women.

Those films among Dwoskin’s oeuvre which do have a clearer narrative (though are no less introspective for it) often feature Dwoskin himself, as an object of interest for the female protagonist, and focus on his relationship to her both as characters and as actor and filmmaker. One of these, 1974’s Behindert (‘Hindered’), was critically acclaimed in Europe. It saw Dwoskin as a disabled man in a relationship with an able-bodied woman, showing how the power imbalance between man/woman intersected with that between able-bodied/disabled.

Because both the dramatized romantic relationships and the cinematography were affected by Dwoskin’s disability, he was seen ‘as’ a disabled filmmaker. Dwoskin felt pigeon-holed by the critics, resenting the way his disability divorced him from the context of his wider filmmaking project. Several collaborators, Trixie among them, had been fascinated by Dwoskin’s physical form – the impotence of his legs contrasted with the strong shoulders which he used to hold himself up on crutches.

Dwoskin himself seemed to oscillate between willingness to make use of this in his films (which he acknowledged attracted increased attention) and withdrawal into his usual fare of ‘art for art’s sake’ to evade the concomitant objectification. His 1981 film Outside In, which he produced to mark the International Year of Disabled Persons and described as ‘the visual impression left during the process of integration into the so-called able-bodied society over twenty odd years of adulthood, transformed into visual metaphors’, was acclaimed in France, and shown on Channel 4, but it could never quite reach mainstream status.

In other respects, Dwoskin’s disability is inseparable from his contribution to the history of experimental and auteur film. One is his bold exploration of sexuality from the perspective of a man in a disabled body, and his insistence on doing so on his own terms. Another is his choice of subjects from other marginalised groups in society: his 1986 film Ballet Black aimed to bring the Ballets Nègres, one of Europe’s first Black dance companies, out of obscurity and featured archival readings and interviews with dancers from the original troupe, including Astley Harvey and John Lagey.

Later in life, Dwoskin’s mobility issues worsened and he took up the use of digital cameras, which were lighter and easier for him to carry, earlier than many of his contemporaries. He also largely edited his films on software such as early iterations of FinalCut Pro (one of the challenges that presented itself to the project team when trying to get a sense of his editing process). It remains the case today that disabled practitioners are often ahead of the curve when it comes to new creative technologies, but rarely receive the credit for innovation that able-bodied peers receive when they adopt them later on.

You can read more about Dwoskin’s films on the project blog.

Opening up the box: digital forensics and data exploration

Dwoskin’s archive presented many questions which are at the heart of discussions about developments in the digital humanities, and which were simultaneously opportunities and challenges. As well as an extensive paper archive, Dwoskin left 22 computer hard drives of material, which he used concurrently. The purpose of the digital work package was to extract the files from these hard drives for digital archiving using methods that kept the hard drive intact, make the contents accessible, and look for patterns in the data. Another aspect was the preservation of his films by digitising them using the latest technology as well as hand manipulation of the image.

This is much easier said than done. Recuperating the data involved system emulation, format migration, sourcing old components and data exploration. To give just one example: to edit his films, Dwoskin used a now-obsolete version of FinalCut Pro that is too old to be run on most computers. Even with the right operating system/software combination, without specialist tools, it is impossible to open a file without changing its nature. Is preserving it exactly as it was more important than accessing the content in order to gain insight into Dwoskin’s editorial process?

This is just one of the ethical questions posed by the archive that could not be addressed by any individual member of the team alone. As ‘born-digital’ material (i.e. that which has not been scanned or otherwise transformed from any analogue original) becomes more and more common, this is a problem that most scholars researching any public figures will have to confront.

Deciding what should be extracted for analysis is a task also complicated by the conflict between accessibility and privacy. Dwoskin’s hard drives totalled a vast 12TB of data, made up of 4 million files. In order to determine what privacy considerations governed the material – legal and subjective – the team had to know what it was, but to know what it was they had to analyse it.

A sample of the physical objects which held Dwoskin’s archive. As you can see, many are in formats largely obsolete today. (Photos: Rachel Garfield)

The team describe a broader sense of ethics as one of the project’s biggest challenges. Many of the hard drives, as well as a collection of pre-VHS video tapes, contained recorded conversations that someone would have to listen to, in order to ascertain if doing so breached the privacy of someone still alive.

For example, some of Dwoskin’s hard drives contained artworks created out of pornographic images and it was unclear whether these were artworks or just playful sketches. Some of the mini DV tapes digitised as part of the project included footage of S&M practices. Footage that went into films was covered by the consent given in the filming process, but the status of material that was not actually in the completed films was not as certain, and therefore raised ethical questions regarding who might have access to it.

The team started by asking questions that did not rely on the content, such as identifying which hard drive was likely to have been Dwoskin’s main computer, and which roles they played in his work cycle. Focusing on the social dimensions of data – volume, variety, velocity, and veracity – in conjunction with Reading’s Archive Services, the project managed to provide a level of access without disclosure of sensitive information.

For example, they visualised Dwoskin’s emails by type of email (business vs. personal), showing that, like most of us, his inbox was dominated by online grocery orders (in Dwoskin’s case, from Ocado). Given the volume of most inboxes, this is an approach that could work for content that has to be public (such as politicians’ inboxes) – it could aid the researcher in finding the material of interest.

For the archive team at Reading, the Dwoskin archive was a huge case study for archival descriptions, arrangement and access. Visualisation for content analysis versus visualisation for planning the archival process (i.e. to find which content is of interest) are two completely different processes; any kind of workflow to be recommended would change depending on whether it was the researcher or archive extracting the data, whether the archive was providing content or a service, and whether the researcher was a participant (as in the case of the project team) or a consumer. Ultimately the project aimed to make the process as participatory as possible for all concerned.

For the digital experts on the team, the opportunity presented by Dwoskin’s archive was to show correlations between Dwoskin’s technological activity and his personal life, an historical context that could only be given by the Art researchers. Dwoskin’s use of software, edits made to his films, and email correspondence could be measured against known information about his artistic development and interaction with others. These could then further be presented in innovative ways, giving researchers unique access to Dwoskin’s editing choices and creative process.

The digital forensics approaches were applied to reconstruct events; humanities research supplied the influences in Dwoskin’s life; the result was a composite of one man’s personal-professional history, his creative process, and his technical environment. Or in other words, digital humanities.

Two innovative ways in which these strands of the project came together are shown below. One is a sunburst visualisation, one of the team’s approaches to ‘opening up the box’ while preserving the original order as far as possible. The diagrams are interactive, allowing the user to zoom in to see how the files are arranged. Each section is a file folder, and the colour reflects how recently it was changed. This can be used in conjunction with other timestamps such as time of creation, and put in a context of version history – how many drafts were involved in the process of creation of an authorial item.

Sunburst showing file system of ‘Disk 1’, measuring 104.29GB with 9993 files/folders

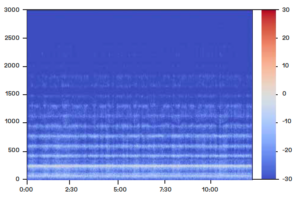

Another is the use of visualisations to illustrate the audiovisual qualities of Dwoskin’s films, such as the durations and types of shot (e.g. close-up vs. extreme distance). This example, Moment, is a study of a woman’s face before, during, and after orgasm. Aside from the opening and closing titles, it is a single shot. The only movement consists of the woman. The soundtrack, by Ron Geesin, consists of a tape loop.

……

……

Above: still from Moment and audiogram from Moment, with X axis showing time, Y axis showing volume, colour showing density of audio.

Below: visualisation of movement in Moment.

Collaboration as innovation

The Dwoskin Project was made possible by a collaboration between the project team that started a full 3 years before the AHRC bid was submitted. The keys to its success were the creation of an open-minded and friendly environment through ongoing conversations right from the start, to ensure that the project plan reflected shared aims and an equal stake for the entire team. The team regarded collaboration itself as a research methodology, with the logistics thrashed out in the plan. All the research questions were informed by more than one Work Package, as they felt that the more crossovers, the richer the research.

One of the things that made work of this scale possible was the job security of a large proportion of the team, and this project was poignantly placed to highlight the relationship of political infrastructure to creativity. Some of the limitations of the project, which might have seemed due to the digital nature of the material, the team in fact attribute to the project structure, with the research imperative necessitating a shift in technical practice. The cataloguing of the archive, which had to run alongside the research, would ideally have come first. Projects are necessarily selective, and even 10 years of this one would probably have just scratched the surface.

Meanwhile, many of the initial engagement events were scuppered in their planned form owing to Covid-19, but the pandemic expanded access as well as hindering it, as the team quickly moved online. The project’s relationship with the disability community was only strengthened by the events of the pandemic, and the ability of many disabled creatives to attend online events – an opportunity for more equal future engagement that very few artistic or educational institutions have taken up – solidified the links between disabled arts and Dwoskin’s archive.

At the culmination of the project, the team held three big events: an online symposium, ‘Alt+Shift+Archive’; a Focus season at the British Film Institute; and a book launch at the ICA. ‘Alt+Shift+Archive’ was hosted by the University of Reading and featuring presentations from the project team and a wide range of colleagues and collaborators in the field of digital archiving. Presentations were pre-recorded and made available on Discord to stimulate an asynchronous discussion, followed by three live Q&As. In keeping with the ethos of the project as a whole, the event’s flexibility generated a strong level of engagement and much food for thought for future collaborations. The Digital Humanities Hub intends to make Alt+Shift+Archive a fixture of our events programme, cementing the Dwoskin Project’s legacy at Reading.

What is abundantly clear is that not one part of this project could have existed without the others. All of the Work Packages and research questions were contingent on work that was to be undertaken by the others. Dwoskin could have informed a smaller research project – a study of an underrated artist in his historical context – that was relatively traditionalist in methods, however important the artist or the context; this project is testament to the scale and potential that this concept reached thanks to the ambitious collaborative spirit of its researchers. But it is also a testament to the necessity of putting the Humanities back into the digital. As emphatically acknowledged by the digital experts on the team, the data they extracted was given meaning thanks to their colleagues who were experts in Dwoskin himself.

Project team

Below follows short biographies of the team and contributors, to give an idea of the wide range of expertise that went into this project. Please feel free to contact them if you wish to know more about the Dwoskin Project, or to enquire about doing something similar.

Rachel Garfield (Principal Investigator) is an artist who works in video, and writes on contemporary and modern art. Her video work engages with themes of portraiture in film and video, the role of lived relations in the formation of subjectivity, and at times, Jewish identity. Although primarily shown in gallery contexts, her work has an ongoing relationship with the traditions and concerns of avant-garde documentary film. Recent exhibitions include ‘Force/Fields: Three Works on Conflict, Militarism and their Legacies’, screened at Star and Shadow in Newcastle in 2019. She is the author of Experimental Filmmaking and Punk: Feminist Audio Visual Culture in the 1970s and 1980s (Bloomsbury, 2021). As Professor of Fine Art at the University of Reading, where she was also Head of the Art Department from 2017-22, Rachel led the Dwoskin Project. She now works at the Royal College of Art.

Zoe Bartliff (Postdoctoral Research Associate, University of Glasgow) is a researcher working in digital humanities at the University of Glasgow, with a focus on the interaction between textual data and contextual culture. Zoe led the extraction and analysis of data for the Dwoskin Project, combining digital forensics tools with data exploration techniques and archival practice. Her background is in Classics and Celtic Studies and her PhD thesis addressed the efficacy of computer-based methodologies for the analysis of the Medieval Welsh law texts Cyfraith Hywel.

Guy Baxter (Associate Director of Archives Services, University of Reading) oversaw the acquisition and management of Dwoskin’s paper archive, as well as facilitating the digital humanities aspect of the bid development. Guy is currently PI of ‘Sustainable Infrastructure for the Digital Shift’, a project funded by AHRC under the Capability for Collections programme. This will develop digital research infrastructure at Reading, building on the expertise gained through the Archive Services’ participation in the Dwoskin Project and in other research projects such as Staging Beckett. Guy’s broad professional and research interests are in copyright and compliance, cross-domain and interdisciplinary working, photograph collections, performing arts and events data standards (and intangible cultural heritage more broadly), and preservation management.

Alison Butler (Co-Investigator, University of Reading) is a retired professor of film whose work focuses on two fields: women’s cinema and artists’ film and video. Her interests include the relationships between feminist theory and the practices and aesthetics of women filmmakers, the aesthetics of multi-screen installation, and the meanings and functions of projected public art and ways of thinking about cinematic time and space, especially in non-theatrical locations. She is the author of Displacements: Reading Space and Time in Moving Image Installations (Palgrave, 2019) and Women’s Cinema: the Contested Screen (Wallflower Press, 2002) and has published widely on artists’ film, moving image installation and women’s cinema. She has been an editor of the scholarly journal Screen and a Co-Investigator on the collaborative Anglo-Brazilian ‘IntermIdia’ project.

Jenny Chamarette (Co-Investigator, University of Reading) is a writer, mentor, and curator whose research focuses on the areas of complex embodiment in the moving image and on the intermedial relationships between moving images and cultural sites, as well as challenging the traditional lenses through which we view both art and research itself. She led the Work Package ‘The Liberation of the Activist Body’, focusing on Dwoskin’s digital archive, disability activism and cultural legacy. Jenny is the author of Phenomenology and the Future of Film: Rethinking Subjectivity Beyond French Cinema (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), and currently holds a MERL Fellowship to complete a memoir, Q is for Garden, exploring the relationship between queer sexuality and cultivation, an extract of which was shortlisted for the 2021 Nan Shepherd Prize.

Frank Hopfgartner (Co-Investigator, University of Sheffield) is a data scientist whose main research interest is in the intersection of intelligent information access and data analytics, with an emphasis on the analysis and exploitation of personal data and user-generated content. He aims to understand and model how data-driven systems, particularly interactive information retrieval and recommendation algorithms, shape and influence people and society. During the Dwoskin Project, Frank was based at the University of Sheffield and co-led the Work Package on ‘Data Forensics and Exploration for Film Archiving and Research’. He is now Professor of Data Science and Head of the Institute for Web Science & Technologies at the Unversität Koblenz-Landau.

Yunhyong Kim (Co-Investigator, University of Glasgow) is a Lecturer in the School of Humanities at the University of Glagsow, with a background in Mathematics and Speech & Language Processing. She works across multiple topics related to information management and analysis, with a particular focus on areas that bring together artificial intelligence, digital curation, and forensics as part of an information ecosystem. Yuhnyong was co-lead on the Work Package ‘Data Forensics and Exploration for Film Archiving and Research’, focusing on the use of digital forensics to secure recoverable data on Dwoskin’s hard drives. She has published widely on a range of areas including the extraction of metadata and domain knowledge from textual and unstructured data for preservation purposes.

Henry K. Miller (Senior Research Fellow, University of Reading) is an historian of film culture and criticism. He is the author of The First True Hitchcock: The Making of a Filmmaker (University of California Press, 2022), editor of The Essential Raymond Durgnat (Bloomsbury, 2014) and co-editor of Dwoskino. He has taught film at the University of Cambridge and Anglia Ruskin University, and is an Honorary Research Associate at the Slade School of Fine Art, University College London, and co-lead of the Slade Film Project. He has published his research in journals including Critical Quarterly, Framework, Screen, and the Hitchcock Annual, as well as Sight and Sound, the Times Literary Supplement and a variety of DVD and Blu-ray booklets.

The project also benefited, with thanks, from the expertise or assistance of the following:

- Institutional partnerships: Will Fowler (BFI), Ben Cook (LUX)

- The Dwoskin family: Mary and Paul Venezia – Stephen’s sister and nephew

- Steering Committee: Anna McMullan, Robert Darby, Steven Ball, Kate Allen and Lucia Nagib – Steering Committee

- Three artists commissioned by the project to produce work in dialogue with Dwoskin’s: Evan Ifekoye, Margaret Salmon and P Staff

- Sara De Bondt, designer of the Dwoskino book

- Cataloguing and managing the Dwoskin Archive: Jennifer Glanville and Sharon Maxwell, UMASCS (University of Reading)

- Administration: Mark Taylor

- Institutions with which the project has worked: BIMI, BFI, Café Oto, LUX, Royal College of Art, University of Reading’s Centre for Film and Aesthetic Cultures

Bibliography

LUX blog archive (with posts on the Dwoskin project)

Book

Garfield, R. and Miller, H. K. (eds.) (2022), Dwoskino. LUX/University of Reading. [Available for purchase from the LUX store here.]

Articles

Bartliff, Z., Kim, Y., and Hopfgartner, F. (2022), ‘A survey on email visualisation research to address the conflict between privacy and access’, Archival Science 22(3), pp. 345-366. [Available here via Springer Open Access.]

Bartliff, Z., Kim, Y., Hopfgartner, F. and Baxter, G. (2020), ‘Leveraging digital forensics and data exploration to understand the creative work of a filmmaker: a case study of Stephen Dwoskin’s digital archive’, Information Processing & Management 57 (6). [Available here via the University of Reading’s repository, CentAUR]

Bartliff, Z., Kim, Y. and Baxter, G. (2020), ‘Visualisation of hard drive content to support archival processes for personal digital archives’. In: 83rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Information Science and Technology (ASIS&T 2020), 22 Oct – 01 Nov 2020. [Available here via Wiley and also available here via the University of Reading’s repository, CentAUR]

Miller, H.K. (2022), ‘Crash, Bang, Wallop: How J.G. Ballard and Stephen Dwoskin intersected’, in The TLS, 28 January 2022. [Available here via the TLS.]

Miller, H.K. (2022), ‘Prime movers’ (on Dwoskin’s Ballet Black), in Sight & Sound 32.2 (March 2022). [Available here via ProQuest. This link is for access provided by the University of Reading. You must be logged into a UoR account or will be prompted to log in with an account based at another institution with a subscription.]

Miller, H.K. (2022), ‘Cinéma du Look: Stephen Dwoskin and Trixi(e)’, MUBI Notebook. [Available here.]

Miller, H.K. (2020), ‘Moments in love’ (on Moment), in Sight & Sound 30.3 (March 2020). [Available here via ProQuest. This link is for access provided by the University of Reading. You must be logged into a UoR account or will be prompted to log in with an account based at another institution with a subscription.]

~

Notes:

Text of this page by Olivia Thompson (Digital Humanities Officer), based on discussions with the project team, presentations, and publications; reviewed and edited by Professor Rachel Garfield (Principal Investigator). Views do not necessarily reflect those of the project team.