When we think about how our planet’s ecosystems respond to change, we often focus on temperature and rainfall. But there’s another, equally critical player: carbon dioxide (CO2) that has largely been ignored in ecosystem modelling. Recent research from SPECIAL team research assistant Jierong Zhao, highlights just how pivotal CO2 has been in shaping global vegetation over the last 21,000 years. By using an Eco Evolutionary Optimality (EEO) approach, this work sheds new light on how plants (not just trees!), responded to past shifts in both climate and atmospheric CO2.

“It was fascinating to see how strongly CO₂ shaped global vegetation — sometimes as much as climate itself. Studying these past extremes gives us a baseline to understand today’s rapid, human-driven changes and improve future ecosystem models”

Jierong Zhao, Research Assistant UoR, now PhD Student ICL

Climate Conditions of the Past

The late Quaternary period—roughly the last 50,000 years—has been marked by dramatic swings between glacial and interglacial conditions. During the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), about 21,000 years ago, massive ice sheets covered much of North America and northern Europe, and global temperatures were far colder than today. By contrast, the mid-Holocene (MH), around 6,000 years ago, was a warmer, wetter period, particularly in the northern hemisphere.

While climate changes are well-studied, CO2 levels during these periods varied independently from temperature. At the LGM, CO2 hovered around 190 parts per million (ppm)—near the minimum threshold for the type of photosynthesis most trees and cool-season plants (C3 plants) rely on. By the MH, CO2 had risen to about 264 ppm, still below the pre-industrial level of 285 ppm (and much lower than today’s levels of 422.7 ppm).

This decoupling between climate and CO2 allows us to explore how each factor independently affected plant growth and ecosystem productivity.

How We Modelled the Past

We simulated vegetation at the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) and mid-Holocene (MH) compared to the pre-industrial state using the P model, a light-use efficiency model of plant productivity. The P model combines established photosynthesis theory with two eco-evolutionary assumptions: the coordination hypothesis (plants adjust their machinery to available light) and the least-cost hypothesis (plants balance carbon gain with water use).

The model uses key inputs, such as temperature, solar radiation, and CO2, to disentangle how each shaped global vegetation in the past. The model focused on two key aspects:

- Gross Primary Production (GPP): the total carbon captured by plants through photosynthesis, a critical measure of how much CO2 the terrestrial biosphere can absorb.

- C3/C4 Competition: Plants use two main photosynthetic pathways. Most trees and many grasses are C3, while some grasses, particularly those adapted to hot and dry conditions, are C4. These pathways differ in efficiency depending on temperature, water availability, and CO2 concentration.

By simulating vegetation under LGM and MH conditions, and comparing them to a pre-industrial baseline, we could tease apart the roles of climate and CO2.

The LGM: Cold, Dry, and low CO2

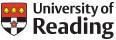

Global vegetation productivity was significantly lower in the LGM than in pre-industrial times. Modelled GPP dropped to about 84 petagrams of carbon (PgC), right in the middle of estimates from other global climate-vegetation models (such as CMIP6/PMIP4), which ranged from 61 to 109 PgC.

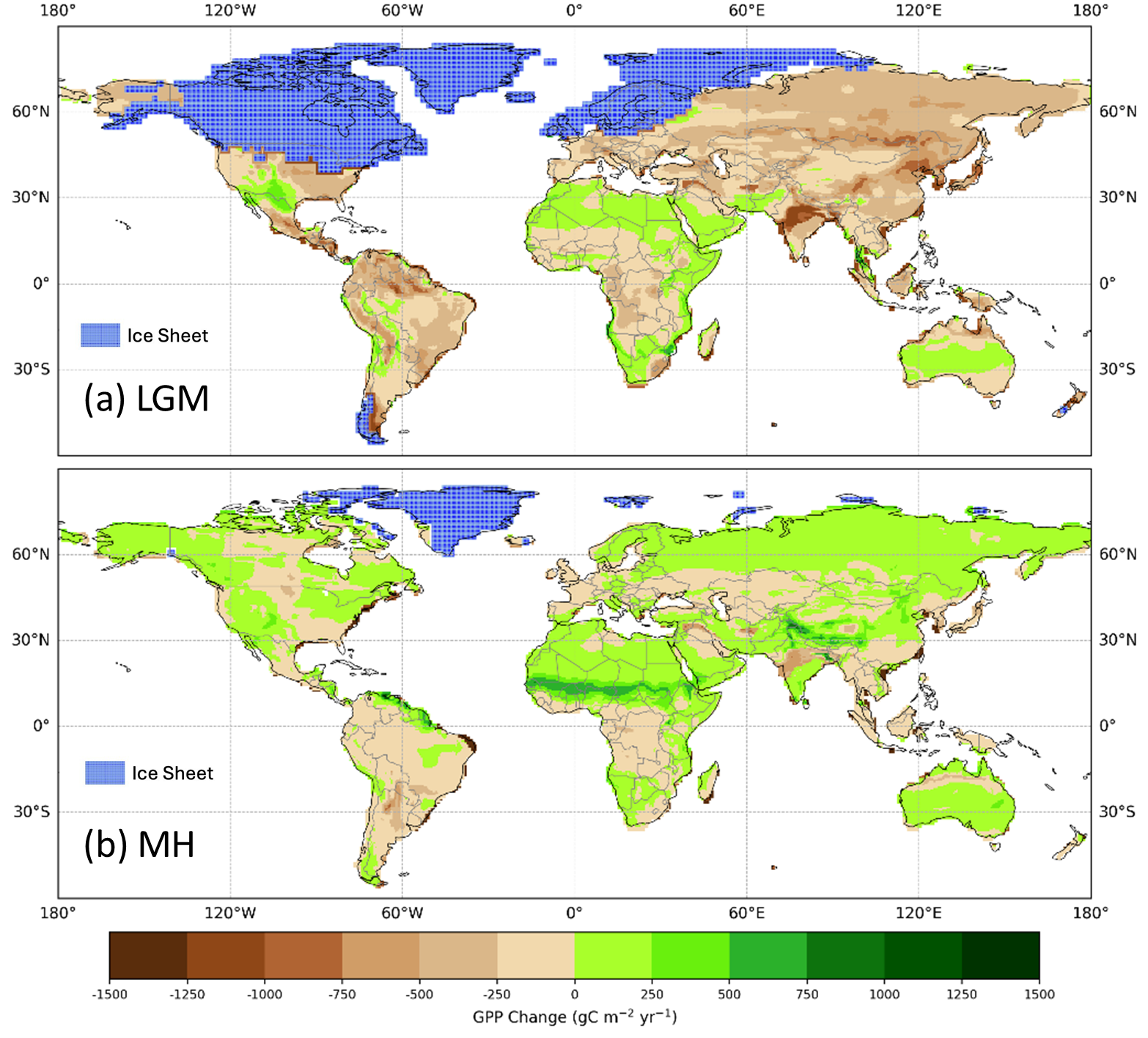

Tree cover was dramatically reduced. C4 plants (typically grasses thriving in high-light, low-CO2, or dry conditions) nearly doubled in abundance, accounting for 40% of the vegetation fraction and 56% of total GPP. This aligns with evidence from pollen and leaf wax biomarkers, which show that C4 grasses were more widespread during the glacial period.

The reduction in GPP was driven by both climate and CO2. The cold, dry LGM climate suppressed plant growth, especially in northern mid- to high-latitudes, where GPP fell by over 50% compared to pre-industrial times. But low CO2 levels also played a near-equal role, limiting the photosynthetic efficiency of C3 plants and further reducing productivity.

In other words, it wasn’t just cold and dry conditions that curtailed global plant growth, it was also the low concentration of atmospheric CO2 that made life harder for most plants.

The Mid-Holocene: Warm, Wet, and Still CO2-Limited

Fast forward to the MH. Warmer summers and increased monsoonal rainfall created conditions that should have boosted plant growth. Indeed, in regions influenced by monsoons, such as parts of the Sahel and Asia, GPP increased. Northern extra-tropical regions also experienced a modest rise in GPP due to longer growing seasons and higher summer solar radiation.

However, the benefits of these favourable climatic conditions were partially offset by still-lower CO2 compared to pre-industrial levels. Even a modest CO2 deficit of 20 ppm reduced GPP by roughly 3 PgC, slightly more than the 2 PgC gain driven by climate. While the MH was generally productive, this highlights an important lesson: even small variations in CO2 can significantly influence plant growth, sometimes overriding the advantages of a warm and wet climate.

Why CO2 Matters

Plants face a trade-off between absorbing CO2 and losing water through their stomata. When atmospheric CO2 is high, they can afford to keep stomata partially closed, reducing water loss while still capturing enough carbon for photosynthesis. Conversely, when CO2 is low, as during the LGM, plants must open their stomata wider to get enough carbon, which increases water loss and limits growth, particularly for C3 plants.

This physiological effect explains why C4 plants, which are more efficient under low CO2 and high light, became relatively more dominant during the LGM. It also shows that CO2 is not just a “fuel” for photosynthesis; it’s a regulator of water-use efficiency, plant competition, and ecosystem productivity.

Lessons From the Past

By using an EEO-based modelling framework, this study provides a nuanced view of how climate and CO2 interact to shape vegetation over long timescales. The findings reveal that:

- The LGM’s reduced productivity was caused by both harsh climate and low CO2.

- C4 grasses expanded their global distribution in response to low CO2, while C3 plants struggled.

- During the MH, warmer and wetter conditions boosted GPP, but lower-than-pre-industrial levels with CO2 limiting this positive effect.

- Accurate modelling of past vegetation changes must account for CO2’s direct physiological effects, not just climate conditions such as temperature and rainfall.

By examining periods when climate and CO2 changes were decoupled, like the LGM and MH, we can better understand how each factor influences vegetation. This helps refine models used for future predictions.

Today, atmospheric CO2 levels are rising at an unprecedented pace, driving both climate change and shifts in vegetation productivity. Lessons from the Quaternary period highlight how sensitive plants are to CO2 levels, and why projections of future ecosystem responses must incorporate both climate and CO2 physiology.

Blog Post Written by Natalie Sanders

You can read the full paper here:

Zhao, J., Zhou, B., Harrison, S.P. & Prentice, I.C. (2025). Eco-evolutionary modelling of global vegetation dynamics and the impact of CO2 during the late Quaternary: insights from contrasting periods. Earth Systems Dynamics, https://doi.org/10.5194/esd-16-1655-2025