My PhD began by asking the question “What are the fundamental drivers of wildfires?” Far from being the first to ask it, I searched for an aspect of this question that had not been investigated in much detail before. As part of recent investigations into the performance of fire models—especially the lack thereof—it has been found that empirical relationships between vegetation and burnt area (BA) are not represented accurately by contemporary fire models (Forkel et al. 2019). This, combined with previous findings that antecedent vegetation has a significant influence on burnt area, provided the impetus for the first paper of my PhD, titled “The importance of antecedent vegetation and drought conditions as global drivers of burnt area” (Kuhn-Régnier et al. 2020).

In addition to quantifying the relative importance of (antecedent) vegetation for BA, our goal was to quantify the relative importance of different timescales, and how this varies regionally. This was to facilitate the application of our results to an improved version of the INFERNO fire model at a later stage of my PhD.

Because INFERNO is a simple statistical fire model, we started by using GLMs to analyse satellite data, since this would allow for the easiest transition of the discovered relationships to the model. However, we soon realised that while the relationships extracted by GLMs would be easy to “plug into” a statistical fire model, they might not be sufficiently representative of the real underlying processes that govern fire, including the myriad interactions between drivers and the associated non-linearities, for example. Therefore, we transitioned to using Random Forest (RF) models instead of GLMs due to their superior flexibility.

The downside of this approach is of course that a more complicated model is also harder to explain. Given the goal of my PhD, explaining why certain predictions are made was key, however! Thus, we employed a variety of techniques to “peek into the black box”, to explain both the importance of different drivers for the prediction of BA and the underlying relationships between these drivers and BA. A key technique we employed was accumulated local effects (ALEs) which are expected to have many advantages over the more traditional partial dependence plots (PDPs) when used to explain models trained on highly correlated data (Apley and Zhu 2020).

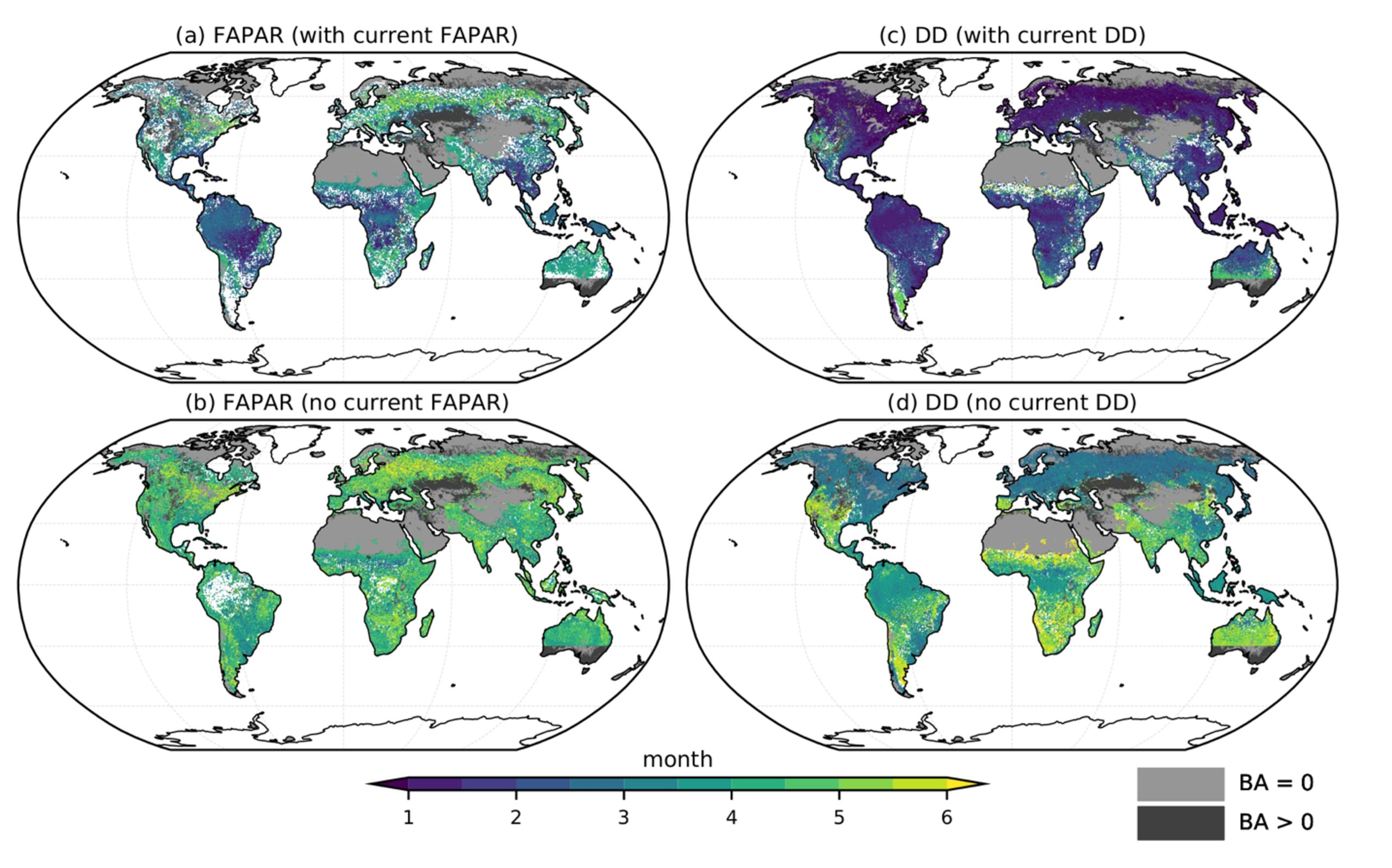

We began by training an RF model on all variables, including versions of vegetation and dry-day period that were shifted in time to represent the antecedent states, yielding 50 variables in total. Then, we checked if this model could accurately predict BA. As seen in Fig. 1, this is indeed the case, with the geographical pattern of BA reproduced well by the model.

To investigate which of the four chosen vegetation variables (FAPAR, LAI, VOD, or SIF) performed best as a fuel build-up proxy, we trained RF models that included only a single one of these (including antecedent versions and other important non-vegetation variables). This revealed that on a global, climatological scale, FAPAR performed best, followed closely by LAI. Other insights from these experiments included the finding that lightning was not significant, supporting previous findings that natural ignitions do not limit global fire occurrence (Bistinas et al. 2014).

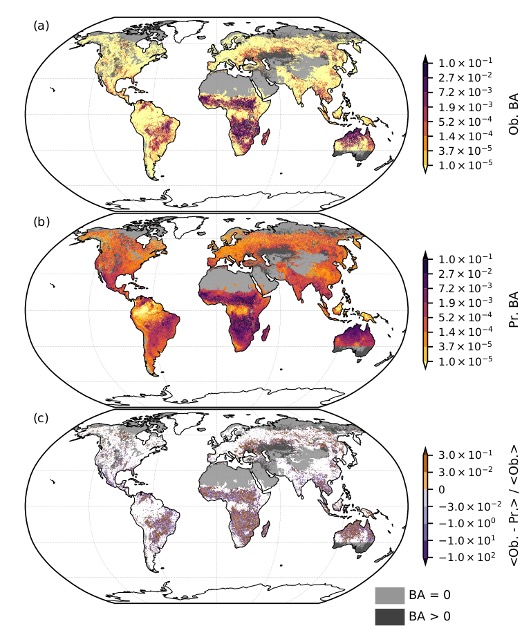

Analysis of the underlying relationships fitted by the model using the aforementioned ALEs technique revealed that, on average, there exist consistent, intuitive differences between instantaneous and antecedent relationships with BA (see Fig. 2). For example, the instantaneous effect of FAPAR on BA is limiting due to the effect that high FAPAR has on fuel moisture. Antecedent FAPAR has the opposite impact, since large antecedent FAPAR signifies fuel build-up prior to the fire season. Similar but opposite relationships can be seen for the dry-day period too, with the exception that for very large dry-day periods there is a consistent positive effect on BA, likely denoting the impact of extended droughts on fire. While we are able to estimate how much these relationships might vary between locations and times by subsampling the original dataset (as apparent from the width of the shaded regions in Fig. 2), this does not reveal the full degree of potential grid-cell level discrepancies.

Nonetheless, we are confident that these relationships can be adapted to be used in an updated version of the INFERNO fire model, especially since we plan to use slightly different relationships for different PFTs, thereby accounting at least partially for the underlying inhomogeneities that result in the observed regional and temporal differences.

References:

Apley, Daniel W., and Jingyu Zhu. 2020. ‘Visualizing the Effects of Predictor Variables in Black Box Supervised Learning Models’. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Statistical Methodology) 82 (4): 1059–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/rssb.12377.

Bistinas, I., S. P. Harrison, I. C. Prentice, and J. M. C. Pereira. 2014. ‘Causal Relationships versus Emergent Patterns in the Global Controls of Fire Frequency’. Biogeosciences 11 (18): 5087–5101. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-11-5087-2014.

Forkel, Matthias, Niels Andela, Sandy P. Harrison, Gitta Lasslop, Margreet van Marle, Emilio Chuvieco, Wouter Dorigo, et al. 2019. ‘Emergent Relationships with Respect to Burned Area in Global Satellite Observations and Fire-Enabled Vegetation Models’. Biogeosciences 16 (1): 57–76. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-16-57-2019.

Kuhn-Régnier, Alexander, Apostolos Voulgarakis, Peer Nowack, Matthias Forkel, I. Colin Prentice, and Sandy P. Harrison. 2020. ‘Quantifying the Importance of Antecedent Fuel-Related Vegetation Properties for Burnt Area Using Random Forests’. Biogeosciences Discussions, November, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-2020-409.