How many of us stop to think about where chocolate actually comes from and how it made its way into our culinary culture?

The story of chocolate has a compelling, rich history that academics like me are learning more about every day.

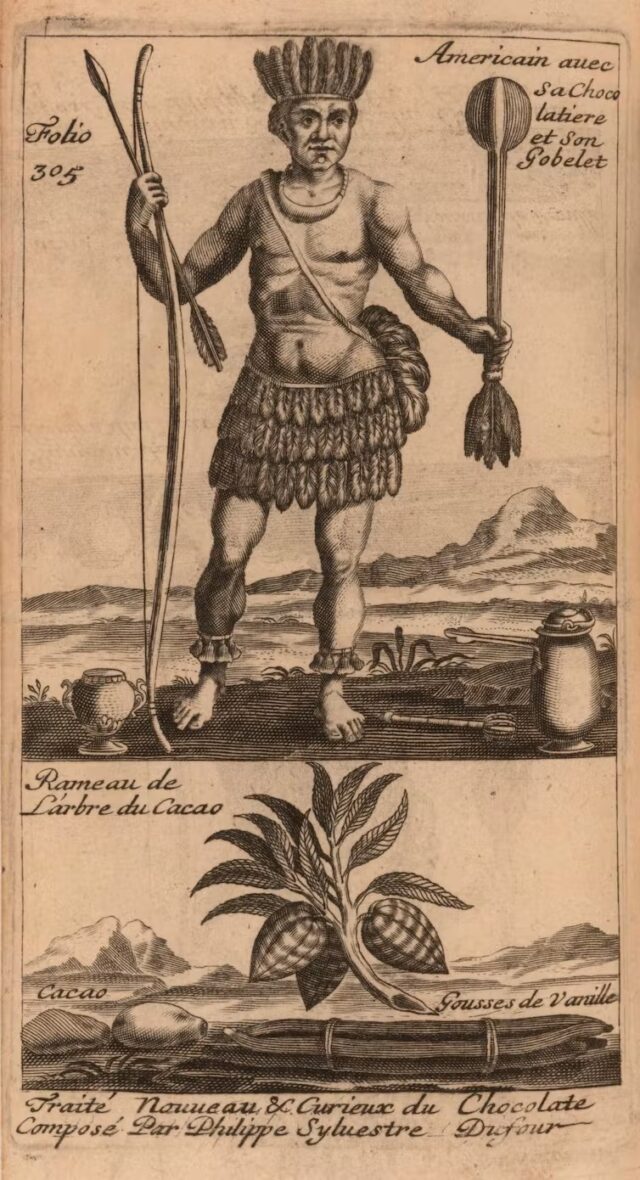

Chocolate is made by fermenting, drying, roasting and grinding the seeds of a small, tropical tree of the genus Theobroma. Most chocolate sold today is made from the species Theobroma cacao, but Indigenous peoples in South America, Central America and Mexico make food, drink and medicine with many other Theobroma species.

Cacao was domesticated at least 4,000 years ago, first in the Amazon basin and then in Central America. The oldest archaeological evidence of cacao, possibly as old as 3,500 BCE, comes from Ecuador. In Mexico and Central America, vessels with cacao residues date to as early as 1,900 BCE.

Cacao is the name in many languages of Mesoamerica (Mexico and Central America) for both the tree, the seed and the preparations that come from it; people who use this word give a nod to that ancient, Indigenous past. Cacao is a convenient catch-all term, the way “bread” in English describes a baked food made of flour, water and yeast.

For thousands of years, Mesoamericans have used cacao for many purposes: as a ritual offering, a medicine, and a key ingredient in both special occasion and everyday food and drink – each of which had different names. One of these special, local cacao concoctions was called “chocolat”.

Colonialists and currency

How did chocolate take off like wildfire when its birthplace has been long neglected? The most popular initial use of cacao in the 16th century, by colonists from Europe and Africa in Latin America, was as currency rather than something to eat or drink.

My research on cacao as money shows its steady development in the crucial role of small coin, as one of several commodity monies in pre-Colombian Mesoamerica. The Rio Ceniza valley in what is now western El Salvador was an extraordinary producer, among only four high-volume farming centres that greatly expanded the cacao money supply in the 13th century.

Spanish colonists quickly made the convenient and reliable cacao money legal tender for all kinds of transactions. However, they were initially dubious about ingesting the substance, debating its health effects and flavour. The Rio Ceniza valley, known then by the Indigenous name Izalcos, became famous as the place where money grew on trees and newly arrived colonists could make a fortune. Their local, unique cacao drink was “chocolat”.

Crossing the world

Despite a hesitant start, chocolate had become hugely popular in Europe by the late 16th century. Among a host of new flavours from the Americas, chocolate was especially captivating. Most importantly, drinking chocolate became a way to socialise.

It also became increasingly associated with luxury and indulgence, to the point of sinfulness, as well as healthful properties that particularly enhanced beauty and fertility. By the 1600s, Europeans were using the word chocolate to describe cacao-flavoured sweets, drinks and sauces.

Chocolate soon began to change the way people did things. As Spanish literature scholar Carolyn Nadeau points out: “Prior to chocolate, breakfast was not a communal event as lunch and dinner were.” As chocolate became increasingly popular in Spain, so too did breakfast. It was also fashionable as a mid-afternoon or late-night snack, taken with bread rolls or even fried bread – the ancestor of today’s breakfast-time churros.

By the 18th century, a variety of recipes using chocolate filled the pages of European cookbooks, demonstrating how important it had become at all levels of society. Far from its Indigenous Central American origins, enslaved Africans, labouring on new plantations in Latin America and later in west Africa, grew much of the cacao that fed the expanding global market. For makers and consumers, chocolate developed vivid connections to class, gender and race. Chocolate became an evocative shorthand for blackness.

Steep inequalities have become entrenched ever more deeply with the globalisation of chocolate. For example, 75% of chocolate consumption takes place in Europe, the US and Canada, yet 100% of the world’s cocoa is produced by Black, Indigenous, Latin American and Asian people – areas that consume only 25% of the world’s finished chocolate, with Africans consuming the least at 4%.

It is largely produced by hand and is a source of livelihood for up to 50m people in mostly developing countries. The COVID-19 pandemic made things even worse. Reduction in movement, limitations on gatherings, supply chain interruptions and poor access to healthcare hit producing communities hard.

Meanwhile large cocoa buyers and traders reduced or paused their cocoa purchasing for as long as two years to weather the storm of uncertain consumer demand throughout the pandemic.

Inequality, fair trade and farmers

Current trends have deep roots in chocolate’s past. Chocolate consumption continues to grow. Europeans are today’s largest consumers of chocolate and the UK is among the highest in Europe, with a per capita consumption of 8.1kg per year and the largest market for fair trade chocolate.

As the chocolate market grows, so too do problems of social inequality and ecological disruption. Carla Martin, founder and director of the Fine Cacao and Chocolate Institute, and I have explained that a path towards economic, social and environmental sustainability will require a range of significant investments.

The University of Reading has already made vital efforts with the Cocoa Germplasm Database to help farmers identify and access cacao’s genetic diversity, and to understand how genetic profiles relate to greater crop resilience and productivity.

Innovative social enterprises such as Cocoa360 are incubators for addressing the big challenges that cacao farmers face, and charting a more hopeful future for chocolate and those who produce it. Food for thought as you unwrap another Ferrero Rocher this Christmas.

Global Professor in Historical Archaeology at the University of Reading.

This article is republished from The Conversation under the Creative Commons License.