For World Tourism Day 2022, we’re taking a historical perspective. Rachel Mairs writes about dragomans, the accomplished tourism professionals of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Rachel is the recipient of a University Research Fellowship 2022–23 for her research, which draws on business cards and other ephemera to give voice to the dragomans’ own perspectives.

The word ‘dragoman’ is unfamiliar to most people today, but in the nineteenth century, no tourist in the Middle East would be without one. A dragoman was a tourist guide, but much more besides. They made hotel and transport reservations for their clients, arranged transportation of their luggage, explained the local culture and the region’s history, and interpreted for them with Arabic speakers. Many dragomans spoke several European languages in addition to their own. The best among them were highly knowledgeable about the history and archaeology of the Middle East, and were up-to-date on all the latest archaeological discoveries. How can we investigate the history of these professionals in a way that gives full credit to their role in the history of tourism and scholarship in the Middle East?

Perhaps because many tourists were completely dependent on their dragomans – and did not like this dependence – dragomans get a bad rap in contemporary travel accounts. Tourists complain that their dragomans cheat them, provide misleading information, or are too controlling of their movements. Are these complaints fair? Getting the dragoman’s own point of view is more difficult, because we do not have any surviving accounts by dragomans themselves, in contrast to the thousands of travel books written by foreign tourists in the Middle East. Our perspective is also complicated by the fact that many nineteenth century tourists had racist, xenophobic and classist attitudes towards the Middle Eastern people they encountered.

So how can we find out what dragomans thought of their clients, and how they conceived of their own profession? The answer is to turn away from more conventional historical sources – published contemporary accounts in European languages – and towards more ephemeral, material forms of evidence. In my 2016 book From Khartoum to Jerusalem: The Dragoman Solomon Negima and his Clients, I studied a Palestinian dragoman who guided tourists in the period from the 1880s to the 1910s. Solomon Negima is mentioned by name in the published accounts of a few of his clients, but his story is best revealed through a collection of documents I found by chance on eBay. Negima kept letters of recommendation from his past clients and pasted them into a book, which he showed to potential future clients. The letters in the book are written by foreign tourists, but the book is carefully curated by Negima himself. It shows us how he wanted to present himself to the world, and the pride he took in his work.

Solomon Negima’s testimonial book was a chance find, and historians cannot rely on luck. But there are plenty of neglected pieces of evidence out there in libraries, archives, museum collections – and attics – that can help us tell the story of other dragomans. Business cards are a wonderful resource, because they show us how dragomans presented themselves to clients. The examples her, from my own collection, are a goldmine of information. Elias Talhamy gives his summer address in Beirut and his winter address in Cairo, showing how dragomans moved to take advantage of the peak tourist season in different parts of the Middle East. He lists famous past clients, something dragoman business cards often do. In the winter, he is based at Shepheard’s Hotel, which for many years was the best and most expensive hotel in Cairo: Talhamy clearly has good connections in the tourist industry.

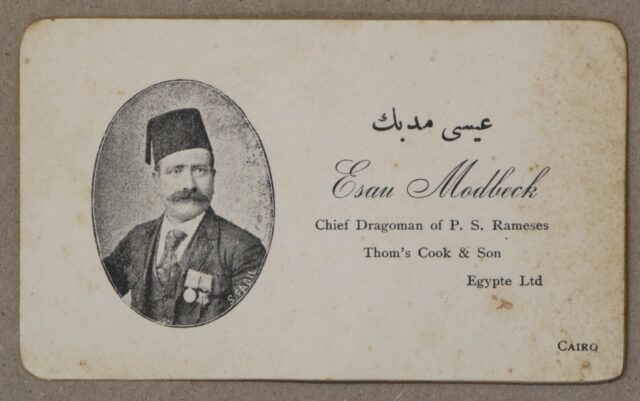

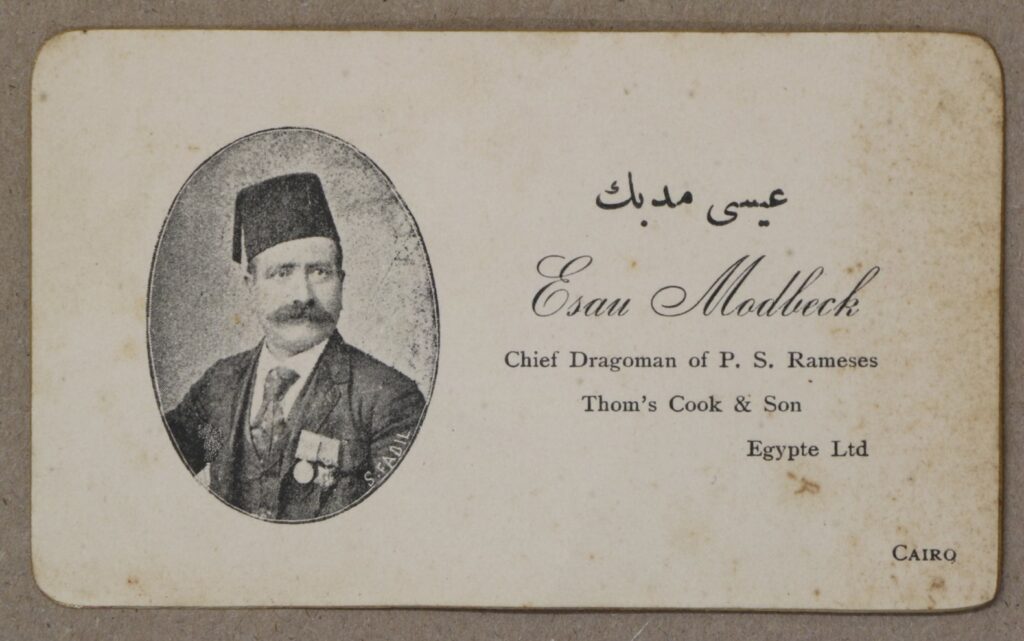

Esau Modbeck’s card has a photograph. He is wearing a tarboush – at that time the preferred headgear of modern, educated gentlemen in Egypt – and medals, advertising his military service and thus loyalty to the British. He states that he works for the travel company Thomas Cook and Co., who held the monopoly for steamboats on the Nile. Like Talhamy, Modbeck shows that he is well connected with elite tourist businesses, and able to offer his clients superior services. You can hear me talk more about these and other dragoman business cards on the Reading Curiosi site here.

During my University Research Fellowship, I will be analysing these and other materials to try to give voice to dragomans’ own perspectives. As well as looking at business cards and other ephemera, I will undertake archival research in Jerusalem, supported by a grant from the Council for British Research in the Levant, and Cairo. My frequent collaborator, Professor Maya Muratov, and I are writing a book on dragomans’ lives and professional networks in Cairo and Jerusalem, which we hope will reveal just how seriously tourists often underestimated them. Dragomans were essential to the tourist industry in the Middle East. Too many of the tourists who complained about petty inconveniences and delays were unaware of the wealth of professional knowledge and experience their guides drew on to make their stay enjoyable.

Rachel Mairs is a Professor in the Department of Classics at the University of Reading.