There was a flurry of PMIP-related activity over the Christmas and New Year “holidays” because of the need to get papers describing experimental results that are going to be cited in the next Working Group 1 assessment of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). I’ve said it before (and I’ll say it again) that setting arbitrary deadlines to match demands for assessment reporting is not a great way of getting good science done. But I was reminded about Mary Beard’s blog comment working on days that “might in other circumstances be to devoted to jollity is, I am afraid, getting to be a habit”, so perhaps if the IPCC did not impose silly deadlines, the academics themselves would. Anyway, it’s good to see that the first of the PMIP4 pre-deadline papers is now out in discussion in Climate of the Past (https://www.clim-past-discuss.net/cp-2019-168/). The paper describes the major features of the PMIP mid-Holocene simulations and briefly compares them with climate reconstructions. The good and the bad news? The PMIP4 simulations are really no different from the PMIP3 simulations: they get the same things right, and the same things wrong. It’s clear what’s bad about this: all that time and effort and we are still not closer to being able to predict large climate changes accurately at a regional scale even if the global-scale features (like land-sea contrast and polar amplification) are fine. But what’s so good about the situation? Well it does mean that we can consider the PMIP3 and PMIP4 simulations as a single ensemble, and think of all that lovely statistical power that gives us.

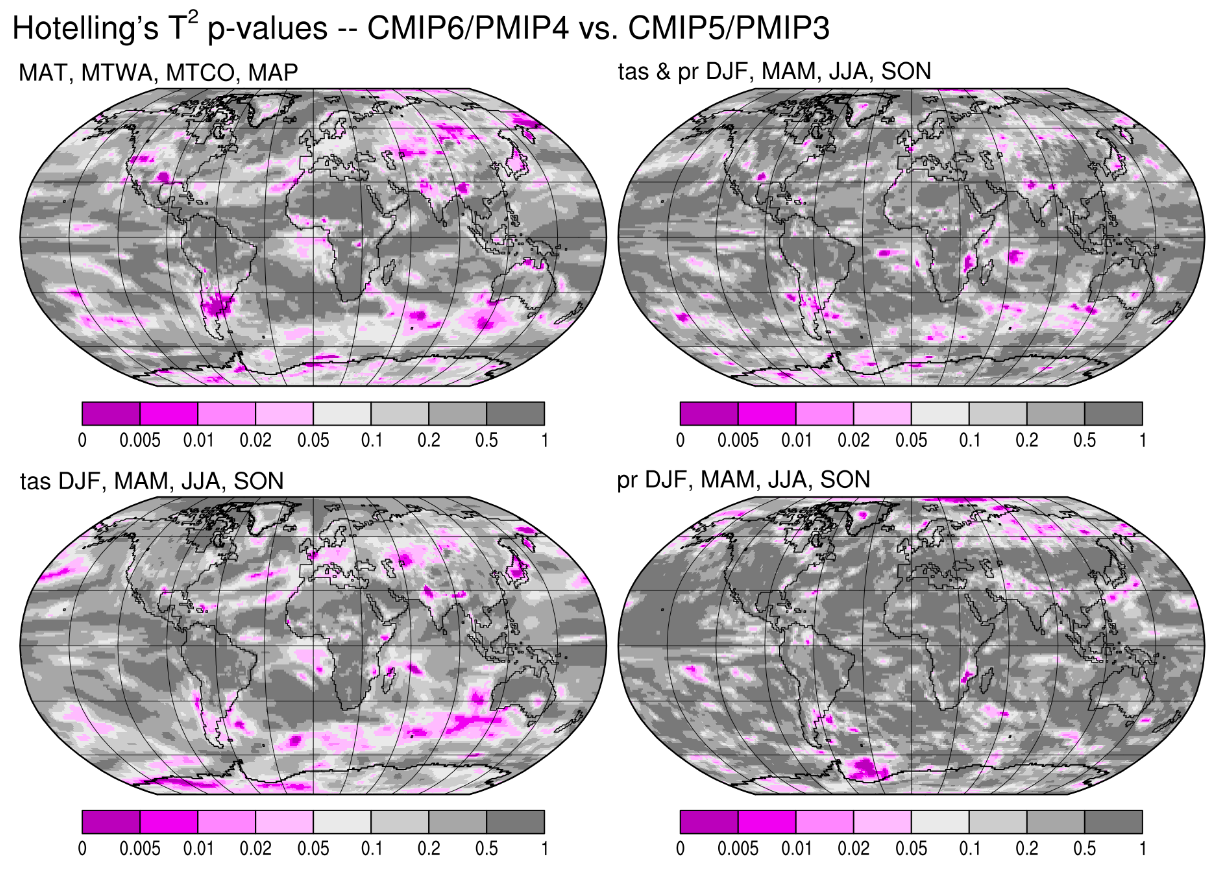

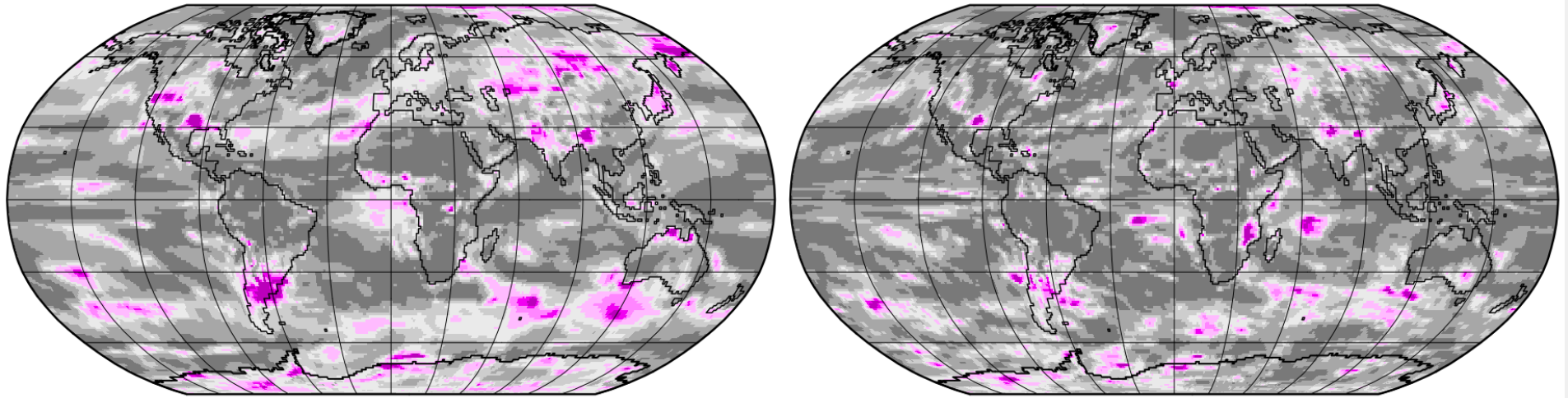

For me, this is the killer figure. A comparison of the two ensembles with respect to different sets of variables, where the purple areas are places where there might be statistically significant differences between the two ensembles. Not a lot of places really and a quick calculation shows that this much difference is to be expected by chance!