In 2014, language learning became a compulsory part of the primary curriculum in England, marking a significant step towards encouraging multilingualism from an early age. However, the success of this policy depends on a complex web of factors ranging from what happens in classrooms to the attitudes of families at home.

To get a better sense of the role of family in shaping children’s attitudes to languages and cultures, we explored the views of parents and carers towards their children’s language learning in primary school. 258 parents responded to our online survey, representing 246 children in Key Stage 2 (age 7 to 11) from 15 primary schools across England. We asked about the children’s and parents’ backgrounds, the parents’ attitudes towards languages and their involvement in their children’s learning of French, Spanish or German.

Why focus on parents?

Research suggests that parental attitudes are an important aspect of motivation. Parents and carers play an important role in shaping how children think about learning. They can influence perceptions of value and usefulness and therefore motivation. However, most studies to date have focused on older learners. With this in mind, we wanted to investigate what happens in the family domain to better understand the learning experience of children of primary school age, when they start forming their views about languages education.

In addition, the role of English as a global language shapes society’s attitudes towards foreign language learning in complex ways. With the current “language learning crisis” in English-speaking contexts and fewer young people continuing with studying languages beyond the compulsory phase, understanding parents’ perspectives feels more urgent than ever.

Positive attitudes, but limited involvement

Despite widespread perceptions (e.g. in the media) that wider society in England may not be interested in languages, the parents who completed our survey had positive attitudes towards language learning. Most agreed that languages are important, both in general and in relation to the specific language their child was learning in school. Parents also wanted their children to continue language study in the future, particularly in the same language, which shows a desire for continuity and progression from primary to secondary school.

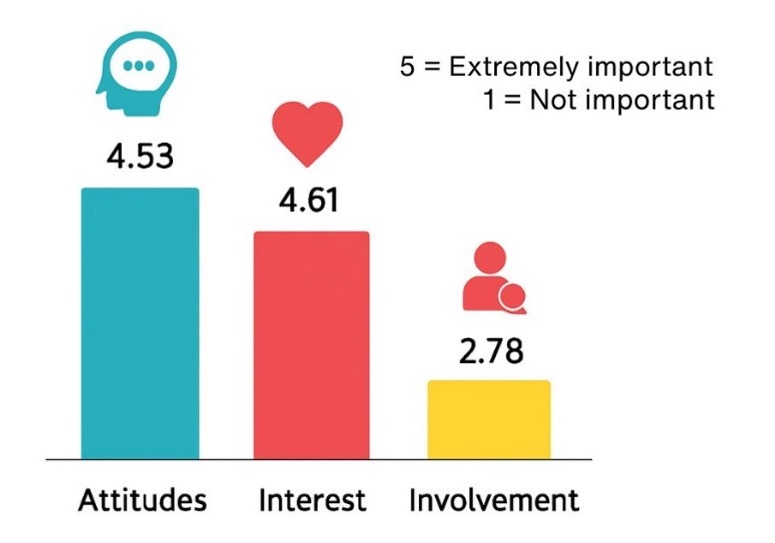

With a closer look at parental views, we identified three key dimensions: attitude, interest, and involvement.

Many parents expressed positive attitudes toward language learning and an interest in what their child was studying. But, limited resources and uncertainty about how to effectively support their child often reduced their level of active involvement. For example, fewer parents reported practising languages or doing language-related activities (e.g. listening to songs) together at home.

Many parents expressed positive attitudes toward language learning and an interest in what their child was studying. But, limited resources and uncertainty about how to effectively support their child often reduced their level of active involvement. For example, fewer parents reported practising languages or doing language-related activities (e.g. listening to songs) together at home.

We also found that parents’ proficiency in the language studied by the child influenced their level of involvement. So, parents who knew some French, German or Spanish were more likely to have more interest and engage directly in their child’s language learning journey.

What shapes parents’ attitudes?

We noticed that, in most research, often the focus is on how parent’s views influence children’s motivation but we don’t know much about how certain views are formed. For this reason, we decided to investigate further to find out what shapes parents’ attitudes toward language learning and try to understand why parents differ in their views.

Three factors stood out:

- Language background: Parents who grew up speaking a language other than English tended to express more positive attitudes towards language learning overall.

- Educational background: Higher levels of education were associated with more positive views about language learning, with the most notable shift occurring around A-level education or equivalent (i.e. age 18).

- Familiarity with the language: Parents who were more familiar with the language studied by their child also tended to hold more favourable attitudes.

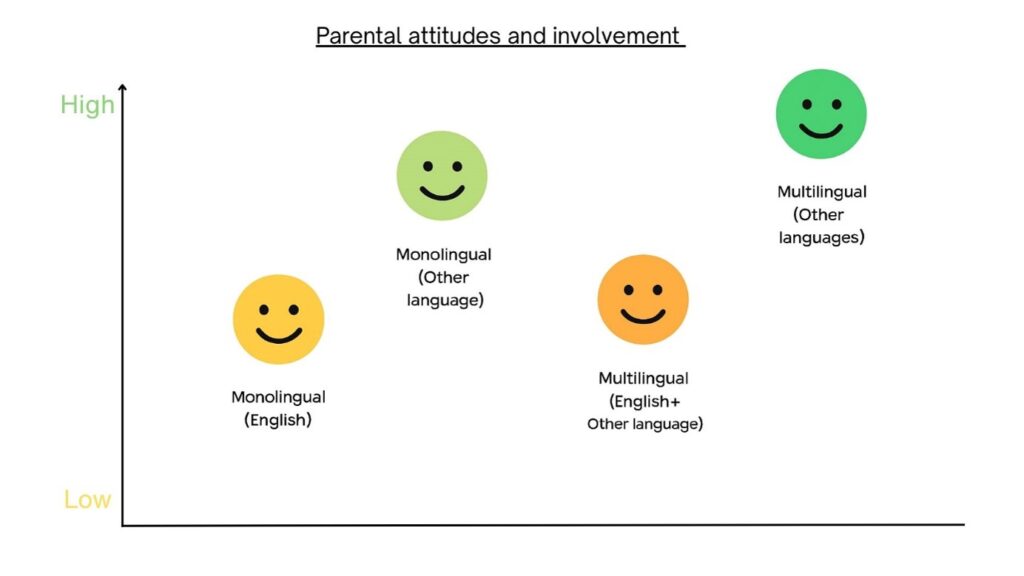

It was interesting to discover that parents’ own language background played the most important role in shaping their attitudes towards language learning. Specifically, we observed that although all parents generally expressed fairly positive attitudes, parents who grew up speaking English (either as the only language or as one of multiple languages) tended to have slightly less positive views and lower levels of involvement in their child’s language learning, than parents who spoke one or more other languages (but no English) growing up.

This suggested that the most important factor shaping parents’ language learning attitudes was whether or not they grew up speaking English, regardless of whether they were monolingual or multilingual!

This suggested that the most important factor shaping parents’ language learning attitudes was whether or not they grew up speaking English, regardless of whether they were monolingual or multilingual!

Overall, we learned that early linguistic experiences, education, and confidence in the language studied by their child, all shape how parents view language learning. Interestingly, whilst socio-economic status is often referred to as a key predictor of educational attitudes, here it wasn’t as important as the language-related factors we looked at.

Linguistic diversity and future language choices

One final aspect we wanted to explore was the views of multilingual families. We found that parents of children with English as an additional language (EAL) showed particularly strong support for language learning. These families not only valued languages more highly but were also more open to learning new languages beyond the main European ones typically taught in schools.

When parents were asked what other languages they would like their child to learn, many chose Spanish, French and German (i.e. if their child was not currently studying that language), but lots of parents also mentioned other languages like Chinese, Arabic, Urdu, Polish, etc. These languages often reflected the languages spoken in the home/community and showed that many parents have a desire for broader language learning opportunities and a general appreciation for learning different languages.

What this means

This study opens a window into how parental attitudes towards primary languages are formed and how they see language learning in school. It is a reminder that many parents care about languages even if they are unsure about how to get involved. Offering simple guidance, sharing resources, or creating opportunities (however small) for parents to connect with what their children are learning could make a meaningful difference.

Parents’ interest in a wide range of languages shows that families value linguistic diversity and are open to more than just the traditional European options. Recognising and supporting this diversity could help build a more inclusive and motivating language learning environment for all children.