Has comfort eating become a pre-occupation for you during lockdown? Find out what we know about the science of our desire to eat and the myths around appetite-supressing foods in this article by Dr Miriam Clegg, Lecturer in Nutritional Sciences, and colleague Suzanne Zuremba (University of Dundee), first published in The Conversation.

There are plenty of adverts and websites that promise to share secrets on how to suppress appetite, or which foods will keep hunger at bay. Protein drinks are frequently sold with the promise of meeting these expectations.

Foods are often developed with the aim of increasing satiety or satiation, but what exactly is meant by these terms? Appetite is our desire to eat. And while hunger is a cue from our body, appetite is a cue from our brain. Satiety and satiation are often used interchangeably in relation to appetite but actually have different meanings.

Satiation is the process that leads us to stop eating, whereas satiety is the feeling of fullness that persists after eating, potentially suppressing further energy intake until hunger returns. In simple terms, what makes us put down our knife and fork is satiation, and what keeps us from starting our next snack or meal is satiety.

Despite sophisticated mechanisms in the body to control food intake, people often still eat when they feel satiated or resist eating when hungry. There are many other factors that influence eating behaviour as well as the body’s satiety signals, such as portion size, tastiness and emotional state.

Worldwide, data reveals that around 42% of adults have tried to lose weight. In terms of New Year’s resolutions, 44% of Britons set weight loss as their goal for 2020. This inevitably opens the floodgates for fad dieting and the marketing of appetite-suppressing products.

What the science says

Currently there is limited evidence to support the effect of satiating foods in obtaining a healthy body weight. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) does not consider a reduction in appetite to be a “beneficial physiological effect” in maintaining healthy weight – and no health claims can be made or placed on food products with regards to appetite.

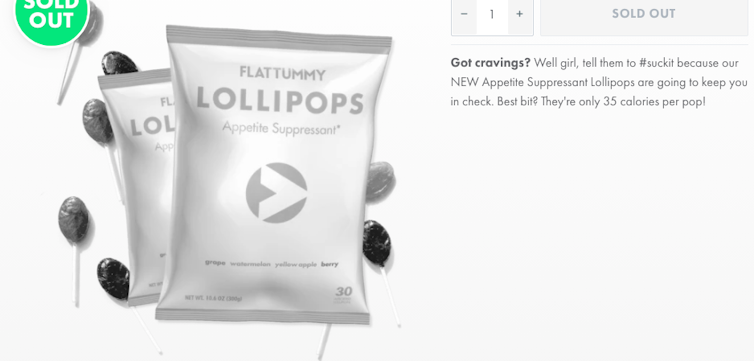

But many food and supplement brands still appear to advertise these benefits, regardless of health claim regulations – particularly outside the EU. A prime example is the Flat Tummy Co’s “appetite-supressing” lollipops which claim to contain “Satiereal, a clinically proven safe active ingredient extracted from natural plants”.

The product is marketed to maximise satiety – but in terms of evidence, there is no robust science to support these claims. This is because there is insufficient evidence characterising appetite and weight, with most studies focusing on one or two days’ effects. But other claims can be made on foods such as “high in fibre” or “high in protein”. These credentials are recognised by consumers as contributing to satiety and can be used without the need for an appetite health claim.

Research from consumer surveys suggest that foods with enhanced satiety are bought not just for weight control but for managing hunger. One of the main reasons people stop dieting is because of hunger or being deprived of their favourite foods. Foods that suppress hunger may not cause people to lose weight but may help them adhere to their diet, which consequently will help them with weight loss.

When is increasing appetite important?

A lot of focus goes into decreasing appetite, but appetite research is not only concerned with reducing food intake and making people feel fuller. In fact, often the opposite is true. For instance, many older people report having diminished appetite for a variety of reasons.

These may include physical factors such as slower emptying of food from the stomach, and social factors such as bereavement, depression or isolation. Reduced physical function (which can make food preparation difficult), sight, smell and taste impairments (which can make food less appetising), medication and dental problems can all influence appetite.

The elderly usually eat less than younger people. They experience fewer hunger pangs and satiation at meals is faster. Together these factors can result in a reduction in appetite and a reduced desire to buy and prepare food, which affects their nutritional health. In this group, foods that promote appetite and encourage increased food intake are required to prevent malnutrition.

Another challenge for older people is that the type of foods they require need to be good sources of protein. Protein is considered to be the most satiating nutrient, but it can increase mouth drying and, if it is meat-based, may require longer chewing, which makes it difficult to consume. Much is still unknown about appetite responses in older people, and more research is needed to explore how appetite can be increased in this population.

At present, there is convincing evidence for the short-term satiating effects of some foods and nutrients, but much less evidence on the longer-term impact of these foods on weight control. More studies specifically designed to demonstrate a causal link, if any, between appetite and weight control are needed. Research which focuses on helping those who have reduced appetite is also crucial, given our growing ageing population and risks associated with malnutrition.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

The University of Reading is a subscribing member of The Conversation. To find out more about writing for The Conversation, email research@reading.ac.uk