… the weighty marble columns.

Euripides, The Bacchanals 591

Leon was waiting outside the inn when Diokles turned up with a staff and a bag of provisions slung over his shoulder. The city was in shade for the sun had not yet risen. To the northeast Mount Pentelikos loomed dark against a sky flecked with clouds. In the streets all was bustle: strings of asses and many ox-carts, laden with food-stuffs, were entering by every gate, bound for the markets. Townsfolk and servants were also on their way to purchase the day’s supplies. The streets were patrolled by itinerant vendors with produce of all sorts.

“Athenian folk rise early”, said Diokles, “for in our warm dry climate the morning hours are best. Let us make for the Acharnian Gate.”

Outside the city walls, they trudged over the level plain, every inch of it cultivated. They avoided the dusty road, finding tracks through market gardens, olive groves and small holdings. Then they began to ascend the gently folding terraces where grape vines grew intensively.

Diokles plied Leon with questions about the countries of the western seas, and while talking they reached the limit of cultivation. The foothills were covered with heathy shrubs and dotted here and there with clumps of pine. Leon said he began to feel at home for the scene much resembled the hills near Massalia.

The travellers crossed a narrow road and Diokles commented: “Down this path came the great blocks of marble for the Parthenon and that enormous unfinished temple of Peisistratos. The masses are brought down on sledges. This road has been smoothed and in places the rock cut away to give a gentle incline. Notice, too, that channels have been sunk in the rocky bank to provide a hold for ropes to ease the passage of the weighted sledges. There is not so much stone being brought down just now.”

They came to a spring and Diokles said, “Let’s rest awhile on this rock, and enjoy the view. From here we can see much of Greece”. They sat and ate the barley cakes and dried fruits Diokles had brought in his bag.

Athens lay like a map at their feet. The Akropolis appeared little more than a stone. Beyond, the tongue of the Piraeus protruded into the sea, which was deep blue. The island of Salamis, dark purple, and Aegina, of a fainter tone, seemed to float on this sea. In the far distance rose the mountains of the Peloponnesus, pink in the morning sun. Diokles pointed out a rounded hump to the west, which he said was Akrokorinth. “It is not so much a rock like the Akropolis of Athens,” he said, “as a mountain. The slopes and summit are well walled. The whole city of Korinth could take refuge up there.”

Diokles indicated the strategic points where the great naval battle of Salamis had been fought and won. Although he was not an eyewitness, it was evident he knew the details of the famous battle by heart. He went on, “In an hour or so I shall show you the site of another famous battle, fought not on sea but on land. Let us resume our journey before the sun rises too high. We’re nearly there.”

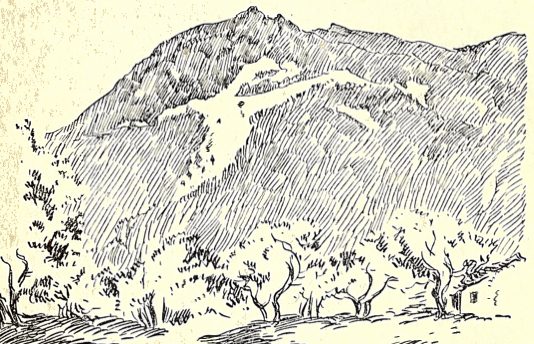

They found themselves on a smooth level road fringed with olive trees, the topmost bluffs of the mountain hanging over. “Those white streaks running down the side of the mountain are screes of marble chips thrown out by the quarrymen. Over there is the overseer’s office. Excuse me a little for I must see him concerning some blocks of marble we require.”

They stopped at a wooden hut with a pleasant view over a grove of olives, the mountain closing in the vista. The overseer was in, and he and Diokles were soon deep in their affairs, while Leon strolled through the grove listening to the birds and looking up at the white screes of marble.

At last the architect appeared. He said, “We have the rest of the day for our own. You will, of course, like to see the place from which we obtain the marble. There is a quarry close at hand. Look! Here come the workers from it, for their break.”

Soon the companions turned a corner where the road was deeply cut into the hill and found themselves in the quarry, surrounded by rock walls seamed with rectangular cracks. All the surfaces were rusty red in colour like the fields around Athens. A battered sled lay in a corner with stout ropes lying upon it.

“Those men we saw surely cannot have come from this place”, doubted Leon, “for there is no white shining marble here.”

“Actually”, returned Diokles, “more than likely a great block of marble will be taken from this spot before evening. Look here.” He crossed to the rock face and there Leon saw a series of cracks forming a long rectangle. His friend pointed out several wooden wedges inserted into the lower crack. Leon put his hand on one and found it to be damp: a great water jar stood near.

“Many besides yourself”, said Diokles, “have come to this spot and failed to find any marble, only rust coloured rocks. See”, and he took up a brown stone and dashed it on the ground. It broke and lay in two fragments. Leon saw with surprise that the broken surfaces had the luminous, slightly granulated appearance of white marble.

Diokles pointed to the wall. “These blocks, fractured by nature into cubes and rectangular prisms, have been covered with a skin of rust by the percolation of water. The quarry-men have inserted the wedges and having wetted them, gone away, leaving the damp wood to expand and work for them. Ah! Hear that!” and Leon heard the groans of rending stone.

“Later,” said Diokles, “wedges will be inserted in the other cracks until the block has been loosened all round. When at last the block has been extracted, the rusty surface will be removed and the block roughly squared. Then it will be levered on to that sledge and with men pulling on ropes and some hanging on behind to guide it downhill, it will finally be brought to the city.”

“Now you have seen what a block of Pentelic marble looks like in the rough, I should like to show you something of interest.”

As they moved out of the quarry, his guide pointed out where the chips of marble had been thrown down. Even the ruts in the narrow road they were following were filled in with gleaming fragments. Presently the road narrowed to a path, which at last petered out altogether.

They were standing on the brow of a descent clothed in undergrowth. On their right was a dark stony hill dotted with bushes and beyond, bathed in sunshine, there opened out a level space with a long tongue of land stretching into blue water, the mountains of Euboea pink in the distance.

“The Plain of Marathon”, said Diokles.

Leon stood silent, straining his eyes.

“You cannot see from here,” said Diokles, “the three mounds under which the bones of the heroes – Athenians, Plateans and slaves – lie with their weapons. That strip of shore was once lined with Persian ships. On the further side of the plain is the marsh where many of the enemy were trapped.”

The two sat down and fell to discussing the memorable fight. At length Diokles said, “We must begin our return journey if we wish to reach Athens before nightfall. We are in better shape than our heroes who, after a grim battle, had to hasten back to Athens, expecting another fight when they got there.”

To read chapter fourteen click on this picture.