The victor stood before the throng

A wreath upon his brow

Pindar

Demetrios and Eugenia put up at Leon’s inn, much to Thalia’s delight. She had wormed out of Doula the tale of their adventures and now insisted on hearing all about the rescue at sea. The child was in awe and decided that she must learn to swim. She even jumped into the little fishpond in the women’s court, but it was too shallow and too small to be of any use. She insisted with much pride, however, that without her finding Doula in the market place, Leon would never have seen Eugenia again. Though true, Phylinna reprimanded her daughter sharply for being a chatterbox.

Demetrios, too, wanted to know the details. He was much impressed by the story of Leon’s running, emphasised by Archippos, who drove to the door of the inn more than once. In fact, Demetrios warmly supported Leon’s idea that he should compete in the foot-racing event at Olympia. “There is time,” Demetrios added, “for us to visit Delphi. I understand you wish to see it before you return. I, myself, intend to consult the oracle about some private business.”

The next few days were spent in preparations for the departure. Purchases were made and horses hired; Archippos was most useful in finding reliable mounts. Leon wrote a letter to his parents, telling them of his adventures, of his proposed participation in the Olympic games and of his forthcoming visit to Demetrios’ home in Syracuse.

One morning, the party finally set off. They said their goodbyes and Phylinna gave them each a parting gift of a jar of oil. Meanwhile Thalia, in her excitement and tears, kept getting too close to the horses’ hoofs. It was a sad farewell, but Leon promised to visit again one day. Archippos was to accompany them in his chariot as far as Eleusis.

At Delphi, Leon and Eugenia were immensely impressed by the great gorge and the mountain overhanging the city. Here Leon found much to fascinate him. In the many statuary groups lining the Sacred Way to the Temple of Apollo, Delphi had Athens well beaten. Moreover, the treasuries belonging to the various city states were full of interest.

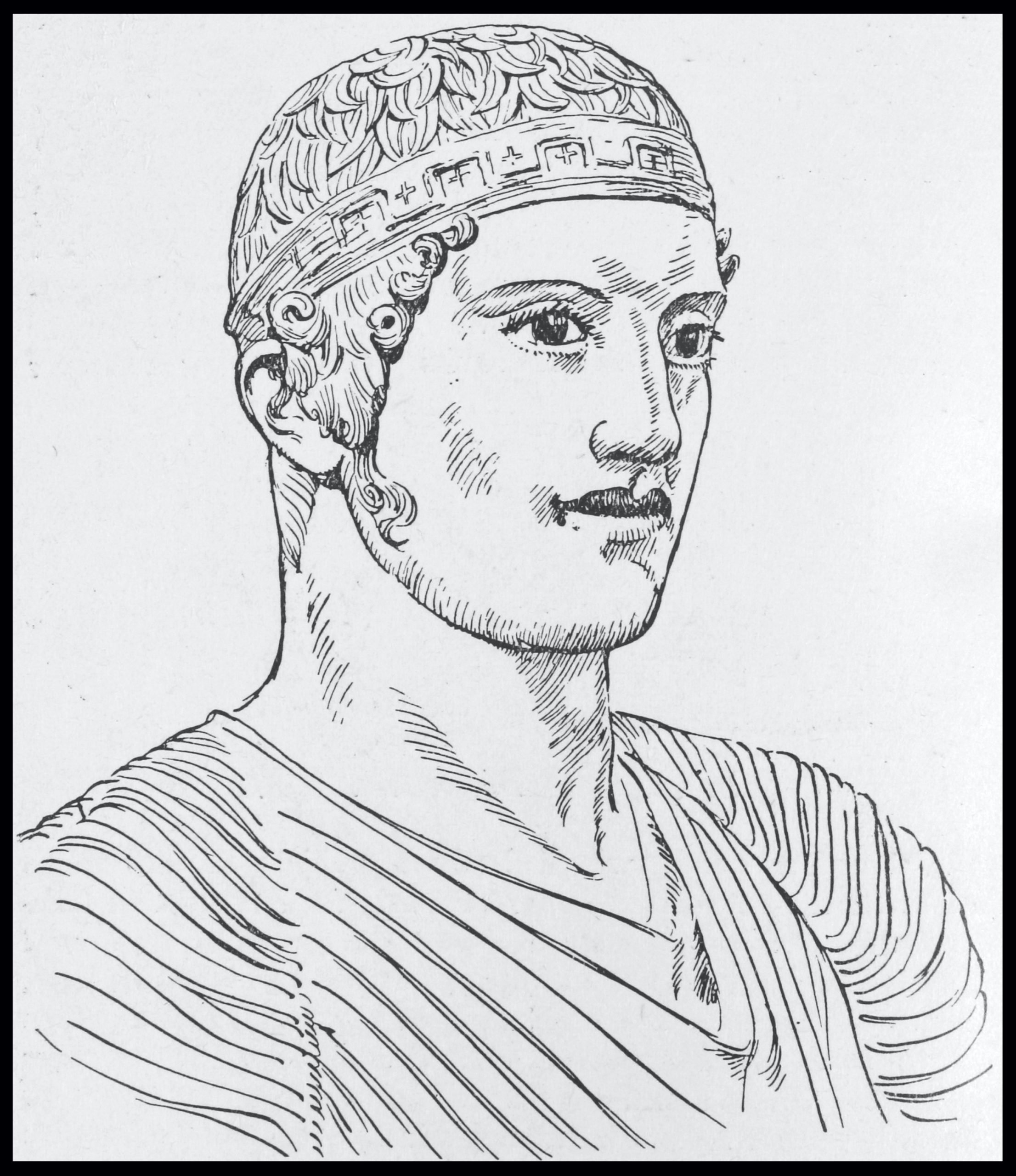

Demetrios said they must visit the fine old bronze quadriga on the city wall, set up in memory of a Syracusan victory in the chariot races. A Victory was crowning the successful competitor, who had alighted and was standing by his chariot. A groom held the horses while the charioteer stood upright in the vehicle, his tunic reaching nearly to his feet. All agreed that the young charioteer was the most notable part of the group. Every detail of his hair was worked out. The whites of the eyes were of silver and the eyelashes were short lengths of bronze wire.

Demetrios returned from his visit to the Pythoness somewhat disgruntled, saying that he was more muddled than before and that the oracle had been delivered in verses worse than any Greek poetry he had read or heard. There followed a beautiful ride to Itea, from where the travellers took ship to the port of Olympia.

On arrival at Olympia they found an experienced trainer for Leon and—for several days—he practiced assiduously. On the morning of the foot races he stood in line with the other competitors. Nearby stood the stewards with their staves, watchful for any malpractice. At the start, an African Greek was off the mark quickly, too quickly according to some of the spectators. He had made good headway before most of the other runners had got into their stride, but Leon was not far behind him. At the turn, the leader, full of confidence, looked back. It was fatal for his chances. On the moment Leon drew level and was a pace in front. Although his rival struggled hard, Leon kept his advantage, finishing a foot ahead. The other runners reached the finish looking more exhausted than the two in front. It was a close race and loudly applauded. Leon walked away from the judges, proudly wearing his crown of wild olive.

Suddenly he became aware of a lad running towards him. Who was this, leaping in the air, shouting his name, grasping his hand? His brother Glaukos and, advancing behind him in more dignified fashion, but with smiles just as warm, his father! “Well done, my son!”

Leon exclaimed a welcome, “You’re here! Why, you couldn’t have got my last letter?”

Autokles laughed, “I thought your brother was old enough to enjoy the Games, and I myself had not seen them for some years, so I chartered a ship. We arrived only last night. When the herald announced ‘Leon of Massalia’ as one of the entrants, Glaukos became very excited. That was an impressive race. You certainly outdid all the other contestants. But now we must hurry; I want to see your mother’s face when she sees you wearing your crown.”

“Mother?” exclaimed Leon.

“Oh yes! Although she couldn’t attend the races she wanted to be here. Your mother and sister are at the inn just beyond the Alphaeus. She was extremely interested in one of the visitors she met this morning – a young woman whom she overheard saying that she hoped ‘Leon’ would be successful.”

Leon laughed, “Here comes the young lady’s father, Demetrios of Syracuse.”

“Ah!” exclaimed Autokles. “This is the man who walked with us to the Games this morning, from that same inn.”

So the four hurried back to the inn to share the good news, and to unite two parties into one.

Autokles’ ship had to depart from Olympia’s harbour almost immediately, but Leon made sure to visit the Altis or Sacred grove, which contained so many marvels – the great Temple of Zeus, the ancient Shrine of Hera, with its wooden pillars, the Treasuries, and the Stoa of paintings. As for the long lines of statuary groups he had almost to run past them but he paused a moment before the flying Victory of Paeonios.

The ship put in at Syracuse and landed all of the party but Autokles, who had to proceed to Massalia without delay.

* * * * *

When Leon at last reached his home city he was accompanied by his new wife, Eugenia, and her old servant, besides his mother, brother and sister. He found the city decorated and a cheering crowd. A team of strong fellows carried him, wearing his faded crown, on their shoulders from the quay. They proceeded through the main streets to the Temple of Artemis, where the chief priest gave him his blessing and a herald recited his exploit. The ceremony closed with Leon taking off his crown and handing it to the priest, as a votive offering. The wreath was hung in the temple porch and pointed to with pride for many a long day, until it was eaten by ants. The bronze Artemis had a better fate. Leon sent the money he had been awarded by his home city to his friend Sokrates and those young men who had helped him in the Athens stadium.

And what of Thalia? That is another story. It is enough to say that, for years after, a birthday gift came to her from Massalia, with a letter from Leon. Once the gift was a portrait of Eugenia and her small son. As Thalia could not read, she used to take her letters to the priest of the little Niké Temple, who was as interested in reading them as she was in hearing the news of Leon of Massalia.