Dark Salamis, washed by the sea,

For all time famous are thy shores

Wherever Greeks assemble.

Sophokles, Ajax 596-599

While at the masons’ yard Leon had noted a very old man who sat in a sunny corner. He was blind, and every morning came hobbling in, tapping with his stick until he reached his niche.

At the sound of his tapping Diokles turned to Leon, saying, “You should have a talk with old Androkles. He claims to have known ninety summers, and has seen much in his time. Even now, although he can no longer use mallet and chisel, he likes to come and sit here, saying that the hammering and sawing are music to him.” That day the old fellow had found his corner and, comfortably seated, was singing a quavering song.

“He’s singing some song of the past, I’ll warrant. Marathon, Thermopylae, Plataea, the Peloponnesian war – he’s lived through them all,” said Diokles.

Leon approached the corner. The song stopped, and the old man turned his head. His skin was ruddy and healthy despite the thousand wrinkles which creased his features.

“Good day! father Androkles,” ventured Leon. “Your song is pleasant on this fine morning.”

The old man raised his head. “Greetings, my young friend. Sit here by me and I will tell you my thoughts. I was thinking the air is soft and the sun shines much as it did at Salamis.”

“Salamis! Even you could not have fought at that battle.”

“No, master, but I saw it all. I was a lad of ten summers at the time. I remember how I enjoyed the short trip on the trireme a few days before. The ships were taking the non-combatants from the mainland to the island of Salamis. It was unpleasant standing in the waiting crowd at the Piraeus, wedged among grown-ups. I could see nothing but the masts of the ships. We had to put off in small boats. I remember being afraid as a big sailor leaned over the ship and lifted me out of the boat. However, once aboard, I lost my fears and clambered everywhere. I got among the rowers and hindered them, until the rowing master threatened to throw me overboard. After that I hurried back to my mother and my aunt at the stern. From there I watched the steersman straining at his oar. I can still hear the splash of the oars and the cries of the officer giving time to the rowers.

“There were priests on board and they bore the old image of Athene – the most sacred thing in Athens – swathed in its embroidered robe. They intended to hide it until the troubles were past.

“We were several days on the island and during that time had only bread and water. One morning, there was a great outcry among the folk, ‘the Persians, the Persians’. Smoke was rising above the city, and then flames. My mother began to cry for our home was outside the walls. How the people wailed when they saw smoke and flames rising from the Akropolis. Everyone knew that our temple of Athene Polias was being pillaged and burnt. We learnt later that many brave citizens had died while attempting to defend their sacred rock.

“However, all this was nothing to what my eyes beheld a day or so later. Our fleet had ranged itself, oar to oar, behind the long tongue of land, called Kynosura, which projects from Salamis. Some said the Greek fleet numbered three hundred ships. We could not see the Persian fleet but it was said that the entrance was completely blocked with their ships. Moreover, the Egyptian contingent had blocked the western entrance to the Bay of Eleusis. On the mainland not far from the shore we could see the great Persian army being drawn up. And high on Mount Aigaleos, we later heard, Xerxes was sitting, waiting to see the Greek fleet destroyed. He expected his presence would ensure victory.

“If our men were defeated, we would be trapped and at the mercy of the Persians. Wanting a better view, I climbed a great rock overhanging the sea a little distance away. At the top I looked eastward. The sight took my breath away. Between island and mainland stretched a fleet many times greater than ours. The Greek ships now looked miserably few. I offered hopeful prayers to Athene.

“I saw a Persian ship detach herself from the fleet, rowing between Salamis and the mainland. More followed, all nose to stern. As I watched, a great clamour of trumpets came from below. My heart thumped as the Greek sailors, soldiers and spectators joined together in singing a paean. I looked again and there was the Greek fleet, rowing straight across channel. As they drew near the enemy, I noted confusion among the Persians. They attempted to turn to meet their opponents, but the Greeks were already on them, their iron-shod beaks crashing into hull or smashing oars. The single line of the Persians was easily crushed and sunk. As fast as the others came up the Greeks were able by superior numbers to overcome them. I could hear the clash and splintering of oars, shouts and cries. But what struck me most was the noise made by our people crowding the water’s edge. There were yells and screams as they saw a Greek galley splinter her oars and as they watched desperate encounters between ships locked together. Those poor women imagined their men must have fallen – brothers, sons, husbands or fathers.

“Later in the day, it became evident that things were going from bad to worse with the enemy. Its very greatness was its undoing. Nearly the whole of the Persian fleet was now jammed together, oars interlocked and no space to manoeuvre. Our men had sized up the situation. A Greek ship would back a bit, then row for all she was worth at the Persian ships. The crashes resounded as rostrum after rostrum smashed its way through the enemy’s planking. When the Greeks had holed a ship they attacked another. The Persians could do nothing save shoot arrows and fling javelins. When an arrow whizzed past my ear I crouched down.

“The attack by the Greek ships was now fiercer than ever, and the water was covered with driftage – planking, broken oars, spars and men swimming – or drowning. Turning my head away from the battle’s centre, I saw some Persian ships retreating from the slaughter. A cry went up as the women hugged one another and shed tears of joy. Every minute the retreat grew more urgent. Sails were hoisted to assist the oars. I saw one enemy ship, rowing desperately, crash into a helpless Persian vessel unable to move out of her way. It sank, and the first vessel rowed right over it. Just after, one of our triremes sunk a Persian ship, close to the shore. Some of the enemy’s men jumped overboard and swam to the shore. The crowd simply trampled the poor fellows underfoot.

“Now the enemy were dispersing I could see movement in the long lines of Persian troops, a little back of the mainland shore. The sparkles of light from helmet and body armour told what a large force was stationed there. As I looked, that army seemed to melt away. I felt overjoyed.”

The old man’s voice wavered. He stumbled and lost the thread of his tale. Leon fetched him a beaker of wine and he sipped it with relish. He began to talk about the days after the battle, when the refugees had returned and rebuilt their shattered homes. He remembered making excursions with other boys to the shore, playing among the wrecks which lay for years rotting on the beach. Once he found a rusty sword of strange pattern and a small round shield of eastern type. He even found an upper arm bone lying half hidden under a boulder. One of his playmates had better luck than he for he picked up a gold cup of eastern design. The beach-combers, though, got most of the stuff. It was a good harvest for them. In the Piraeus market the stalls which sold second-hand goods were filled to overflowing with all kinds of plunder.

Androkles’ voice faded and he began to nod. Leon quietly left him dosing in the sun, the half-emptied flagon by his side.

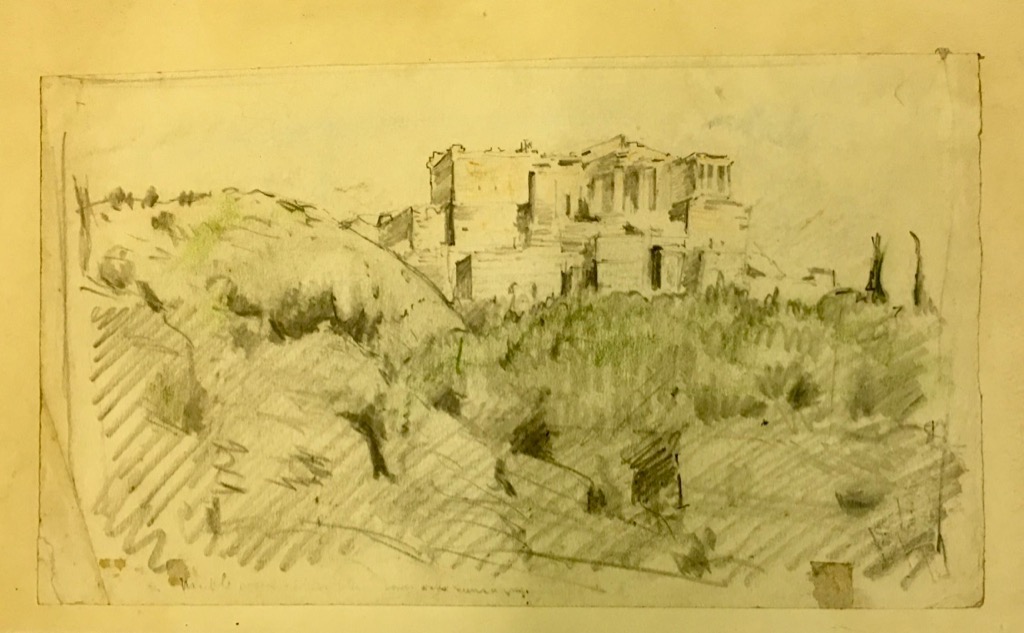

To read chapter fifteen click on this picture.