… with cord pulled taut,

The mason draws his line.

Sophokles, The House of Atreus

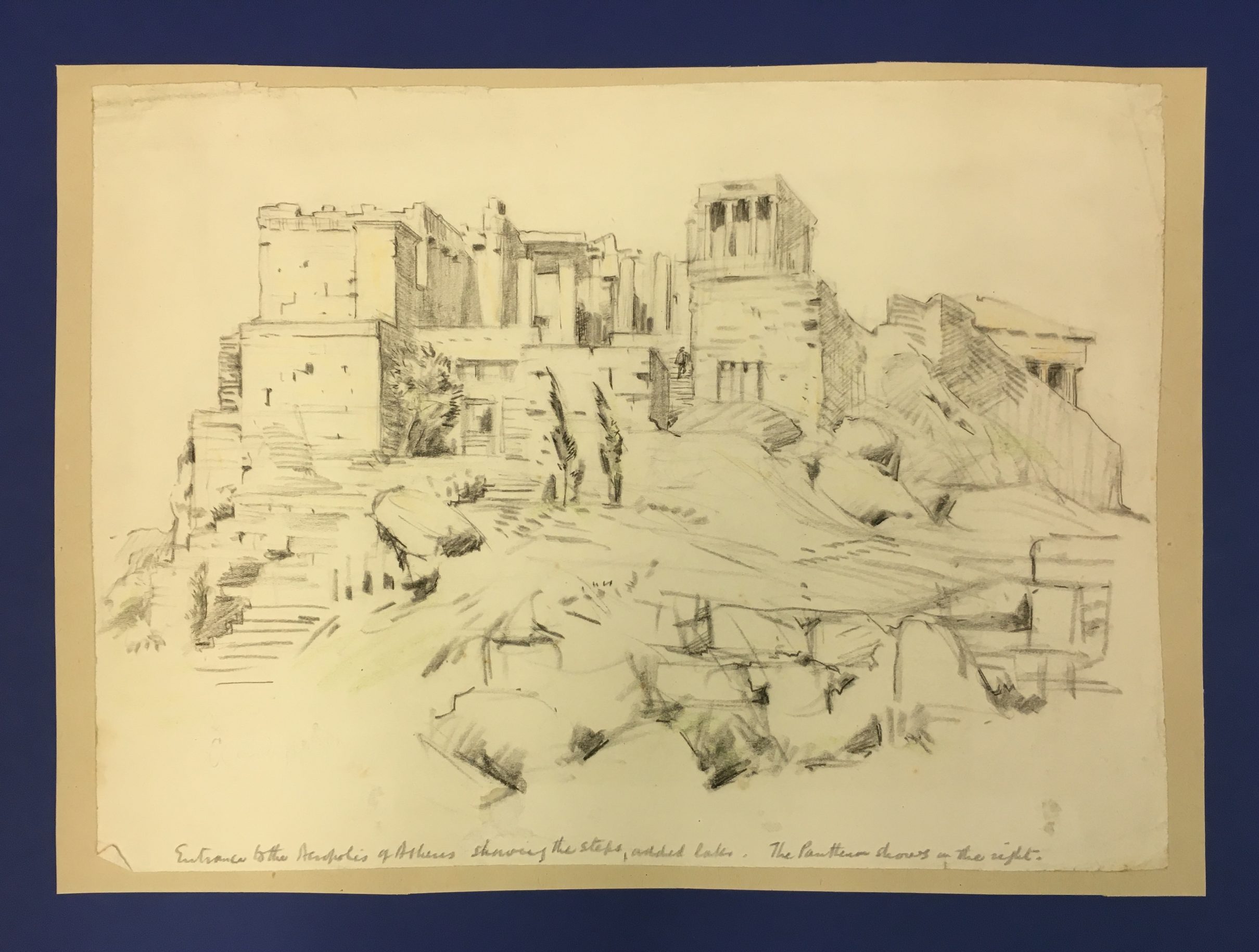

It was a hot day and Leon had climbed to the Akropolis, where the air was fresher. Many others were up there too, some worshipping, some sight-seeing or merely idling. Beyond the Propylaia he turned: the blue of the sea caught his eye, and the mountains beyond with patches of snow on their summits. He strolled around the ramparts, taking in the views, while the noises of the city below came faintly to his ears. It was all so beautiful that Leon had difficulty in turning from it to the temples.

As he walked towards the Parthenon he noted in front of him a man and a small boy. The two had emerged from the scaffolded Erechtheion. Having reached the three high steps on which the Temple of Athene stood, they knelt in respect to the goddess whose great image of ivory and gold gleamed dimly in the warm light from the open doorway.

After a few moments they arose, making their way to the corner of the building. There the father began to talk to his son, taking out a straight edge from his belt and pointing with it. Leon caught some of their talk. The father was evidently familiar with the art of building: he was giving his son a lesson. He climbed to the second step of the plinth on which the temple stood, and beckoned to the lad to follow. They bent down until their eyes were on a level with the top step, looking along its length. Leon heard the boy exclaim: “Why, the step rises in the middle about the width of my palm. The surface is not flat, but curved.”

Leon, mounting the steps, asked that he might look too.

“Willingly,” said the father. “My name is Diokles. As I am an architect these matters interest me much and I wish that they should interest my son. Bend down and you will see what my boy has noted. If instead of looking along the side as we have been doing, you examine the end view you will find a similar rise. Of course, the reason for slightly curving the steps is obvious. Long straight lines appear to sag and this small rise prevents it; but, as you may imagine, much care is required in setting the pavement slabs. A practical advantage is that the water flows away from the temple in wet weather.”

“But, my father”, said the lad. “If the steps are curved in both directions, the effect must be to cause the surface of the pavement at the corner where we are now, to be doubly curved. Has the underside of this great pillar been shaped to fit the pavement?”

“Well done my son. Yes, the base of that pillar is not quite flat; it had to be shaped to fit the pavement. Moreover, the column is not upright.”

“Not upright?” interposed Leon.

“No! It slants backwards and inwards, to prevent it looking as if it might fall outwards.”

“And these flutes or channels running up the column,” asked the lad. “Why have they been cut?”

“It is obvious that they give grace and lightness to the column. They break up the light and shade and so avoid the monotony of a plain surface. There is, too, another explanation. Many think that our great stone temples had their origin in wooden ones. I have told you of the wooden pillars of the temple of Hera at Olympia. So we may suppose that these flutes break up the surface much as the bark of the trunk of an acacia is ridged and fissured.”

“I must now return to my work,” continued Diokles. “I am architect to the Erechtheion. We are hoping to have it restored in readiness for the Panathenaic festival next year.”

He invited Leon to come with him and they walked across to the Erechtheion, somewhat dwarfed by its imposing neighbour.

“Although it cannot compete with the great Parthenon, this building is as wonderful in its own way”, said the architect. “The Parthenon in its grandeur has a sternness and severity which make it a fitting cella for the great goddess, but with regard to the Erechtheion, the idea has been rather to make a sumptuous home, worthy of the xoanon or wooden version of her. Where it lacks size and majesty, it has variety of spacing and delicate adornment.” Leon looked at the beautiful doorway with its finely carved detail. He raised his eyes to the frieze of black Eleusinian marble with the white figures carved separately and pegged into position. He saw, too, the beauty of the side porch with the karyatides supporting its roof.

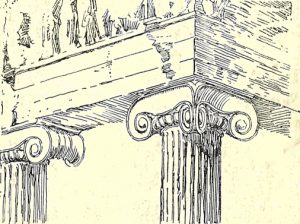

“Again, let us examine the columns of the porch, which we have nearly finished. The strapwork pattern of interlaced circles on the base is an ancient motif from the East, denoting eternity. A carver is up above giving the last touches to the capitals of this porch, before the scaffolding is removed. He is a slave from Lydia but the best carver of ornament in Athens. Would you like to climb up with me?”

They ascended the ladders and walked along the planks to the corner of the porch. The carver, with mallet and chisel in his hands, stood aside to let the visitor inspect the work. Leon admired the exquisitely drawn volutes, the “egg-and-tongue” mouldings and especially the palmette and lotus frieze round the neck of the capital. “The work is amazing,” he said at last.

A call came from below and Diokles scrambled down.

The carver, named Eumares, was delighted with Leon’s praise. Leon asked him if he did figure work? Well, he had done some, but his master kept him at this decorative work because it paid better. However, he did know a sculptor who had just finished a beautiful little group of Artemis and her hounds. “His name is Kephisodotos, and he dwells near the masons’ quarter. Hand me your tablet I will write the address and a line of greeting.”

Leon thanked him and descended to the ground where he found Diokles. They continued their discussion until a mason came, asking advice of the architect, who invited Leon to go with him and see a wall being built.

Diokles showed him the wall being dressed. On another part slaves were rubbing the surface with blocks of sandstone, which they dipped continually in water. “That’s the last stage. It’s dull work but necessary,” said the architect. “We do not use mortar like the Egyptians”, he went on. “Athens is liable to earthquakes so the stones are laid without it.” He suddenly broke off and looked about him. “Where is my son?” Leon pointed and there he was, walking on the Akropolis wall. The boy turned, saw them and jumped down.

“He is a fine lad and takes after father”, Leon said.

Diokles laughed. As he parted ways with Leon he said, “Farewell. We must meet again.”

To read chapter twelve click on this picture.