The gods, a stranger made me,

Remote from my dear land.

Euripides, Helen 690–95

It was late afternoon when the ship reached the Piraeus, Athens’ harbour. Small boats quickly surrounded her and landed its goods and passengers. Once standing alone on the quay with his belongings, Leon felt uncertain among the throng of pushing porters and loafers looking for a job. Suddenly he heard his name being called.

He turned quickly. The speaker was a sharp-featured man, quietly dressed. Leon noted a roll of papyrus in his belt, an ink-well slung from his neck and a reed pen behind his ear; he was obviously a clerk.

“I am Sosias, slave of Nicomenes the banker,” he explained. “My master received a message from your father by the previous ship alerting him of your coming, and arranging the amount of credit which you can draw upon our bank.”

Leon was taken aback for a moment. This man, carefully dressed and well-spoken, could well have been a Greek citizen. It would be hard to tell slave from freeman here.

Leon confirmed that he was indeed the young man Sosias was looking for.

The slave proved useful and efficient. He was immediately in negotiation with the driver of an ox-wagon to take Leon’s baggage to Athens. Then he took the visitor to the port authorities, vouched for Leon’s identity and paid the dues, which he noted on his papyrus roll. He turned to Leon:

“Most of the foreign Greeks live at the Piraeus to be near the business on which they have come, but my master understands you intend to study the glories of Athens, so he has arranged for you to put up at the inn kept by the widow, Phylinna. The place is respectable; the landlady has a good name for looking after her guests, and it is quiet, save for her little chatterbox of a daughter. At the moment you may find many other guests who have come for the festival of the Dionysia. You may prefer to walk to the city: you will hardly care to travel in the carrier’s slow ox-wagon. When you reach the Piraeus Gate at Athens, anyone will direct you to your inn. I am sorry I cannot be your guide, but I have many matters here to settle. From where we stand the road runs direct to the city. You cannot miss your way.”

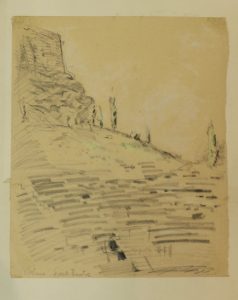

After they had parted ways Leon stopped to haggle with an Egyptian peddler for a walking-stick. Then he made his way along the road from the port, anxious to reach that wonderful city of which he had heard so much. He knew he was on the right road for on either hand at a little distance were the remains of the great walls torn down only three years before when Athens had only just escaped pillage and destruction. However, everything seemed all right now; the peasants were hard at work in the little red fields, hoeing in the vineyards or tending the old gnarled olives. Leon was wistfully reminded of his father’s slaves looking after the olives at home. Just then he surmounted a rise in the road and found himself nearing Athens. The low evening sun had emerged from the clouds and although the city lay obscured in shade, light caught and gilded the summit of a great rock rising almost sheer – the Akropolis. Yes, there was the Parthenon, like a temple of gold. And there, just visible, the Erechtheion. He had never expected such beauty. Although he could see only the temples’ roofs and the upper part of their columns, that was enough for Leon. How cheerful and welcoming both rock and temples looked. The sight was well worth the voyage and he knew that this moment of vision would never fade from his memory.

He came to the Piraeus Gate and inquired of an officer for his inn. When prompted Leon showed his credentials to the officer and gave the banker’s name as reference. As he was passed through, the guard remarked that he had arrived in time for the “tragedy” tomorrow.

Sure enough, when Leon reached the inn he found it crowded with visitors, mainly from the islands, come for the festival of Dionysos. Thanks to the banker’s good arrangements, however, Leon was received hospitably, and shown at once to his room. Though small and bare, it opened on to the courtyard, with its green vines climbing the pillars and its well in the centre. As he sat on the couch and took off his sandals, a small girl of eight or nine came in with a copper basin, a painted terracotta ewer, a large sponge and a towel over her shoulder.

“I’m Thalia”, she proclaimed, “come to wash your feet,” and she proceeded to pour water into the basin.

“Aren’t you rather young for such work?” asked Leon, as the child went about her task.

Thalia looked up, still sponging Leon’s toes.

“It’s the first time I’ve done it,” she replied, “but we’re very busy this evening, and mother said I must help her. I don’t mind washing your feet,” she went on, “but I should hate to wait on some of the other guests.”

She was drying Leon’s feet now.

“Very refreshing after my walk” laughed Leon. “When I write to my family I’ll tell them you looked after me nicely.”

Thalia took the basin out and then, commenting on how dusty Leon’s sandals were, proceeded to clean them. She slipped them back on Leon’s feet, then stood looking at him.

“Mother says your meal shall be brought in immediately. Are you going to the theatre tomorrow like the other guests?”

“I suppose so,” replied Leon. “Do you know what the play is?”

“It’s a tragedy by someone who’s dead, Soph — Sopho — I’ve forgotten his name.”

“I expect you mean Sophocles,” said Leon, “and the tragedy will be given in his honour, he no longer living. Are you going?”

“No, mother says little girls like me are not allowed in, but I don’t mind. I expect plays for grown-ups are long and dull. Though I’m sorry I shall miss the revellers returning at night with the image of Dionysos. They are all dressed up like goats and other creatures.”

“Never mind,” Leon consoled, “if I see it I’ll tell you about it.”

“Thank you. Mother’s calling. I must run.”

After his meal Leon went to the door of the inn and looked about him. The sun had set, but the sky was still bright. Not far away the Akropolis rose and the upper part of the Parthenon could be seen, now suffused with reflections from rosy clouds. Feeling refreshed, Leon set out at once. He wanted to visit the Akropolis right away.

He made his way through the narrow streets and presently came before the triple-gated Propylaia which stood facing the western sky. Leon thought of the saying that the Athenians were proud of their myrtle berries, their olives, their honey and, last but not least, their Propylaia, and he felt they had right to prize this magnificent entrance.

He climbed up until he reached the platform of the Niké temple. However, his gaze was drawn past the little shrine to the distant sea. He was reminded of a story he was taught at school. Just here old Aegeus must have stood waiting for the return of his son Theseus and, seeing the black sail which had been left up by mistake, in despair had thrown himself from the rock. Leon looked down. A nasty tumble it must have been—and tragic.

He passed through the gates and knelt for a moment before the great bronze Athene, then approached the Parthenon. In the half-light it looked as if it had grown up from the rock. It was beautiful.

Apart from a few attendants busy cleaning up at the altars, Leon was alone with the statues on the pediments, the metopes, the frieze deep in shade and the groups of statues lining the path to Athene’s cella. He found, on arriving at the east end of the temple, that the bronze doors were closed; he must wait another day to see the gold and ivory statue within, but he knelt for a moment before the shrine. Leon then wandered across to the triple-celled Erechtheion, which was partially shrouded with scaffolding, although the little porch of the maidens – with its noble “caryatides” – was unobscured.

He strolled behind the porch and found the ancient sacred olive tree, its great hole scarred and pitted. He could see where big branches had been lopped off. It was amazing that the tree had survived all that destruction and burning eighty years ago by the Persians. As he looked, a bird appeared in the mouth of one of the holes in the trunk. It was a Little Owl. It hopped out onto a branch and peered down at Leon with its pale staring eyes. Here was Athene’s bird. The Little Owl (unlike the Brown or Screech Owl) came out by day; Leon thought it a very apt symbol for the clear-sighted goddess. He took an Athenian coin from his pouch and, in the half light, studied the Little Owl depicted on the reverse: a good representation he thought.

He walked round the ramparts looking down on the city below. It stretched in all directions, the streets leading away to the gates giving the appearance of a wheel. The dusk settled on the city; the streets were thinning fast. A trumpet-call rang out from the Propylaia and a gate clanged. It was time for Leon to leave.

To read chapter four click on this picture.