Dionysos! What deity is he?

Euripides, The Cyclops 520

Leon awoke from a deep sleep to find the sun shining into the courtyard. The inn was strangely quiet after the bustle of the previous evening. When his hostess brought in a meal of porridge, barley cakes, fruit and wine, she asked “Are you not going to the theatre? Most of Athens are already in their seats.”

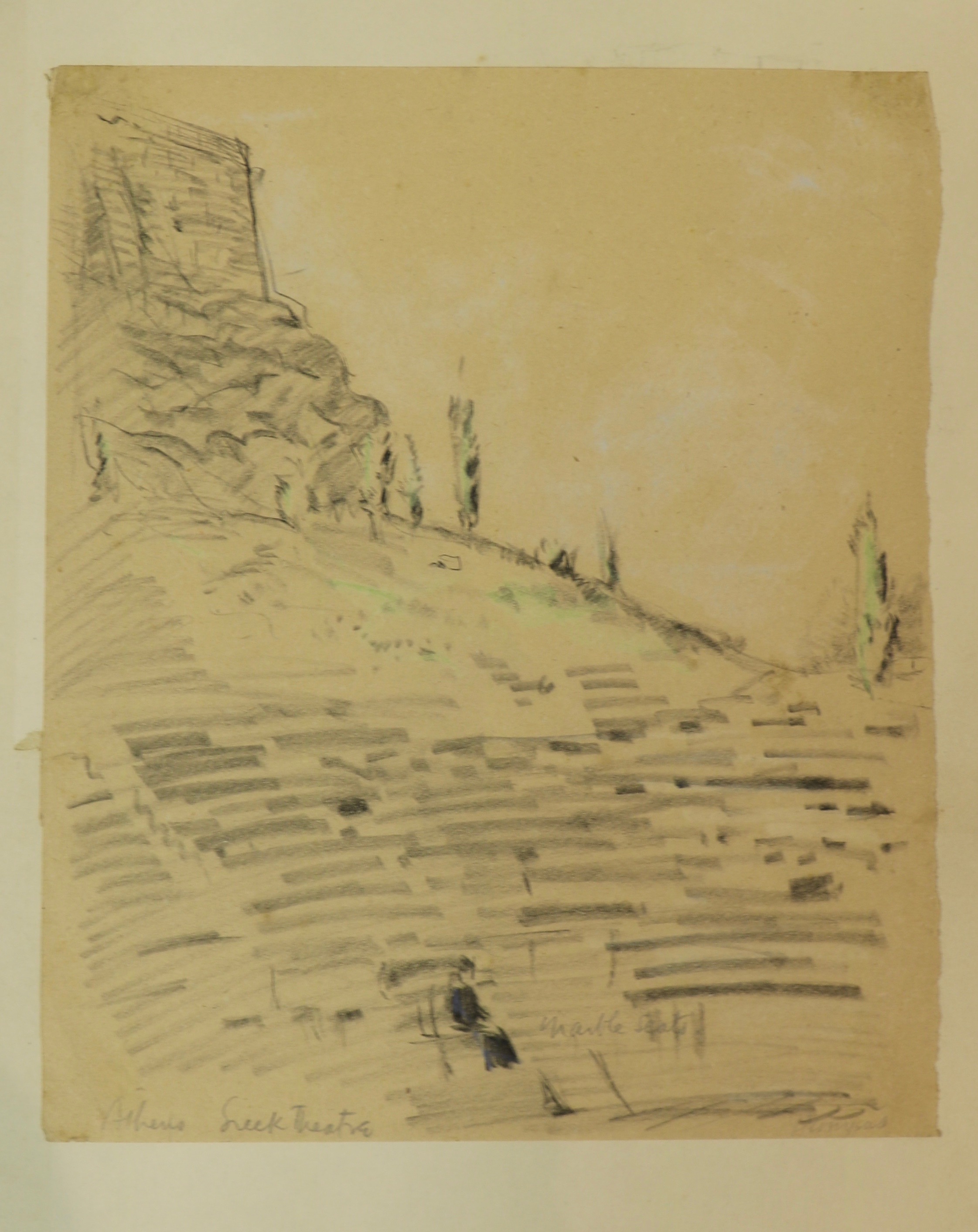

Leon quickly ate his meal, donned his cloak and set out for the theatre. He had no difficulty in finding his way for he knew it was under the Acropolis, which was in sight all the way. When he arrived at the gates of the theatre he was astonished, looking up, to see such a vast throng, reaching almost to the great wall of the Acropolis. This was a crowd greater than he had ever seen in his home city. How quiet they were – out of respect, he supposed, to the memory of the great poet.

At the gate were a few late arrivals, among them a poorly clothed man, who was arguing with the gate-keeper.

“No free seats today,” Leon heard the gate-keeper say. “You should have made sure of your seat yesterday, when you could have had it for nothing.”

The man, disappointed, was turning away when Leon offered to pay for him. The offer was at once accepted and Leon paid the gate-keeper, who told him that the only seats left were at the top of the theatre. The two ascended one of the gangways, climbing up and up until they found seats – rough steps hacked out of the bare rock.

“It’s a good crowd,” commented his companion, “but not so tightly packed as sometimes. You should see the place when the comedies are played, especially if it’s one by Aristophanes.” He broke off to point out the chief priest of Dionysos who was taking his seat in the middle of the front row on a marble chair. Turning again to the comedies, he said, “There was more fun in the old days. Anyone might find himself up to ridicule – officer of state, philosopher, even the chief priest of Dionysos. When the Frogs was performed, the actor playing Dionysos even insulted the audience!” However, the last few years it seemed to have been expected that living people, especially if in office, were not to be picked out and mocked.

Leon remarked they were a long way from the speakers and might find it difficult to catch the words, but his companion assured him that the actors speak clearly and their voices float upwards.

“Why, if this place were empty, you up here, and I, being down there, dropped a drachma on the pavement, you’d hear it.”

Leon then began to ask questions of his new friend, who evidently recognized many among the audience. Was Aristophanes present?

“Yes, he’s the grey haired man sitting on the right, three rows from the front.” Leon noted that Aristophanes kept turning round to those behind him, sending them into fits of laughter.

“And Sokrates?” asked Leon.

“My name’s Sokrates,” answered his neighbour, “and there are plenty more present who answer to it; but you mean, I expect, old Broadnose, the philosopher.” He stood up and scanned the rows, then pointed out an oldish man with a broad nose and protruding eyes. And there was young Plato by his side, taking notes as usual of what Sokrates was saying.

“Did you see the Clouds?” asked Leon.

“Did I not? I kept my eyes on Sokrates all the time. He laughed like anything at the ridicule poured upon him, so that folk who were looking at him to see how he would take it began to laugh with him. Of course, they all knew the sort of man he was, that he made the sacrifices to the gods and would not even take payment for his teaching. Aristophanes meant well, aiming at the philosophers who were turning young men into demagogues, but he might have left out Sokrates. Aristophanes wants to get back to the old days when Athens stood for Hellas against Persia. He doesn’t like it that Sokrates realises those days are gone for ever.”

It also turned out that Leon’s companion had seen Euripides, many times. The playwright had died a few years back in Macedonia, devoured by hounds it was said, though that was rubbish. He was an oldish man when his Trojan Women was produced.

“I didn’t see that” he went on, “for I was in prison for debt at the time, but I saw his last tragedy, the Orestes. That was a noisy play. The actor who played the mad Orestes shouted himself hoarse, and the property men behind the scenes, in setting fire to the gate, seemed likely to burn the whole theatre down. It would have been a blaze. We enjoyed that part. There has been talk of rebuilding the theatre in stone, but nothing has come of it as yet.”

Just then the heralds blew their trumpets and they both settled down to absorb the performance. Leon had attended plays in the Massalia theatre, but he felt a thrill to be in this historic place, the first of its kind in Hellas, and knowing that behind and above him were the famous temples. The play was well performed. The actors’ words came clearly through their masks and they managed to retain their dignity while strutting on their high thick-soled boots. Now and then his attention wandered during the long speeches: somehow he felt more interested in the audience, for here was all Athens before and below him. They, however, were fully engrossed in the play.

At last the play drew to its close. The pair waited for the lower rows of the theatre to clear before they made their way towards the exit. Once outside Leon and Sokrates stopped for a drink of wine, over which a bargain was struck. Leon wanted someone to take him around the city and show him everything of interest: monuments, shrines and the like. Sokrates agreed to spend the next day with him for a modest sum, saying, “I know it all like the palm of my hand and I shall be glad to do so for, since the troubles in Athens, I’ve had no regular work. I have to manage on my magistrate’s pay, and if you’ve seen the Wasps you’ll know that isn’t much.”

To read chapter five click on this picture.