The maddened Bacchanal,

Holding aloft her pine-tipped wand,

Whirls round and round in dizzy step.

Euripides, The Bacchanals

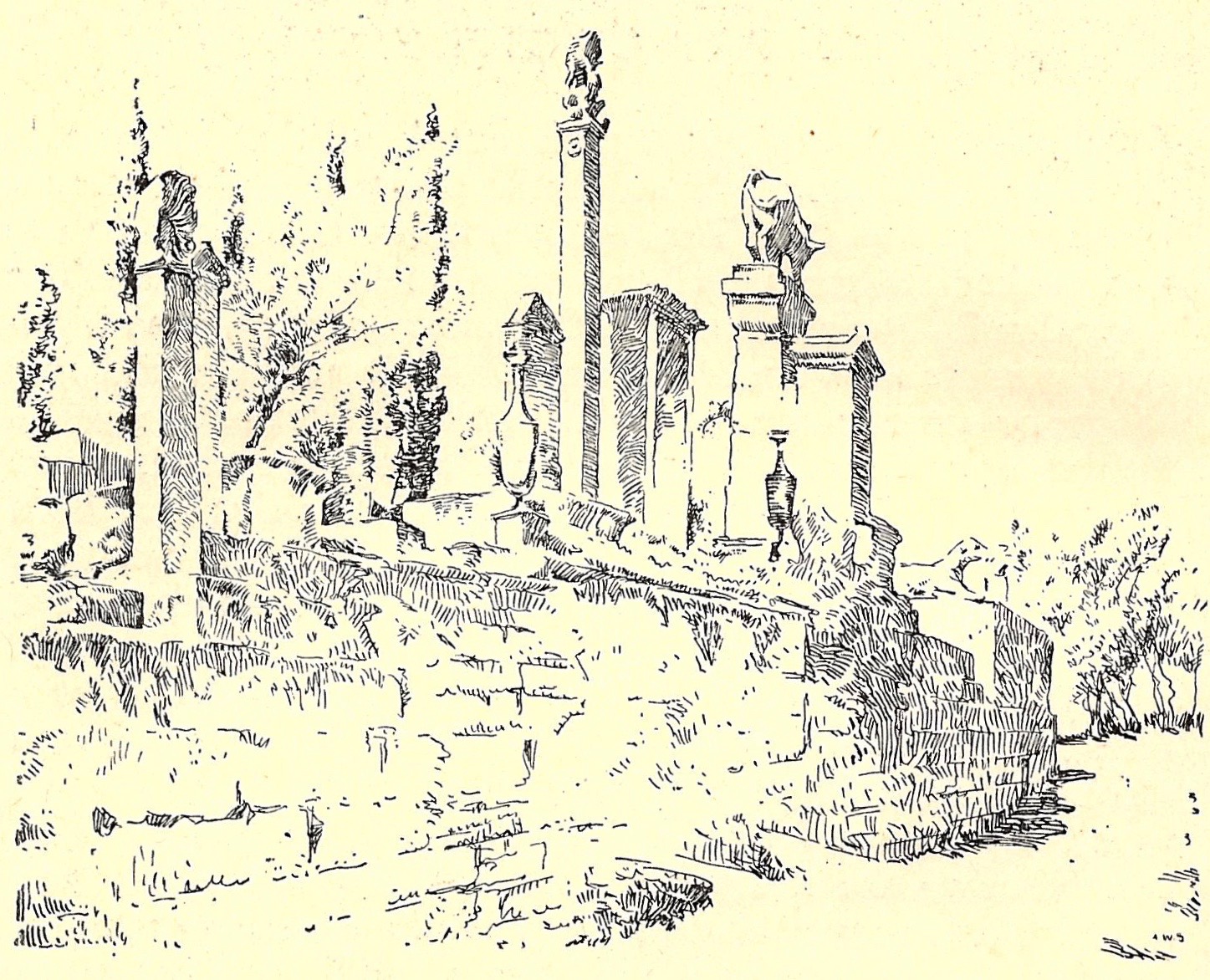

Leon was tired from his day’s outing. His guide had taken him everywhere in Athens. They had visited shrines, temples, fountains and admired numerous statues. In addition to the Agora and markets, Leon had seen the Areopagos, the Pnyx, had gone through the double gate of the Dipylon to view the Street of Tombs and visited the gardens of Aphrodite. They had inspected the theatre and the Odeion and wandered through the great unfinished temple of Peisistratos, standing forlorn. Sokrates had even insisted on their walking out to the stadium—a levelled space surrounded by sloping banks—and pacing the six hundred foot course.

Leon thought it a good opportunity for a practice run, so he took off his cloak, and asked his guide to start him off. His speciality was neither the long nor the short, but the double course. Although his voyage had given him no opportunity to practice running, he did his best, with a spurt at the end. He felt breathless, but was encouraged by Sokrates’ surprise and the warmth of his praise.

“I’d no idea,” said he, “that I was touring a champion sprinter around the city. What a pity the Greater Panathenaia is not on this year. I believe you’d have won a jar of oil.”

Leon laughed, then, understanding from his guide’s remarks that he knew somewhat of foot-racing, asked whether he would have any chance of success at Olympia that summer. Sokrates was enthusiastic. “Every chance, but you must train regularly you know, for at Olympia you’ll be pitted against the best runners in all Greece. I advise you run two or three times a week. If you’ll put yourself in my hands I’ll do my best for you. I’ve raced myself in this stadium when a lad. I know some young fellows who’d be pleased to race you and would consider it an honour to help a man win at Olympia.” After that Leon felt accepted and welcome in Athens. At the end of the day he thanked his guide, paid him double what had been agreed and arranged for his next practice at the Stadium.

Back at the inn Leon was so preoccupied with the day’s events that he took little notice of the clatter going on around him. Everyone was excited about the procession of Dionysos and in particular its return late at night.

Leon was sound asleep when a slave, mistaking him for someone else, awoke him, telling him it was time to leave the house if he wanted to see the procession return. He was cross at being awakened but the slave’s voice was so full of excitement and urgency that he found himself wide awake almost at once. Donning his shoes and cloak he left the house. It was pitch dark, but he followed others carrying torches and arrived at the place where the procession would pass on its return to the little temple by the theatre. Leon listened to the conversations of those around him, wishing he was back in bed, until someone called out, “They come, they come”, and Leon himself could hear noises and see the twinkling of lights.

The noise grew louder until it swelled into a tumult, while the light of many torches diffused a ruddy glow; Leon pressed forward to see better. At first, the procession carried itself with some dignity. In front walked the chief-priest, crowned with young vine leaves and followed by priests similarly adorned, one of whom carried a carefully wrapped bundle – the sacred xoanon – an ancient wooden image of the god. As it passed the spectators fell on their knees. Later, the procession took on a different character. Men, dressed as satyrs and fauns, flourished empty wine skins or carried torches. A fat man, dressed in ivy leaves and being carried by young men, was greeted with applause and jokes. Young girls skipped and danced. Attired as bacchants and dryads, they shrilled Dionysiac hymns while waving the thyrsus, a cone-tipped wand, or swinging festoons of laurel and other evergreens. As they passed they called upon the bystanders to join them. An especially noisy group hailed Leon and a tall girl, crowned with ivy, deftly threw a rope over his shoulders and drew him into their midst.

“A capture, a capture”, they cried.

Leon was drawn along in the shouting throng as the procession wound through the Agora and on towards the Temple of Dionysos. Here they halted and Leon found himself wedged in a dense mass of excited worshippers. Someone had thrown a wreath of ivy round his head so that, surrounded by the drunken revellers, he felt almost a reveller too.

Suddenly there was a cry, “The priest of Dionysos.”

The chief-priest appeared on the steps of the temple and lyres and flutes sounded the first notes of the hymn to close the celebrations. The crowd began to sing, their frenzy increasing with each repetition of the chorus until the whole mass seemed to move as one body.

A herald blew a trumpet and the revellers stilled and grew silent. The priest raised his arms and in a loud voice uttered a prayer. He turned to the multitude.

“Worshippers of Dionysos”, he proclaimed, “the god regards you with favour. You have celebrated his festival and have performed the rites he is due. Now he bids you farewell for another year. Go in peace.”

It was the signal for every light to be extinguished. In a moment all was dark. The crowd dispersed, quiet apart from the patter of sandals and smothered laugher as people bumped into each other. Leon waited until his eyes had become used to the darkness and he could discern dimly the mass of the Akropolis against the sky; then, conscious that the crowd around him had melted away, began to make his way back to the inn. It was not far but he failed to get his bearings. He found himself walking down a deserted street, most of the dwellings standing sombre and quiet. Leon took a turning and then another; it was evident he had lost himself. Presently he saw a light ahead of him and he made out a shortish man, accompanied by a slave holding a torch. Leon, explaining he was a newcomer to the city, inquired the way to the inn of Phylinna.

“I am pleased to help any stranger Greek visiting our city during this festival. My name is Antikles. I live here, by the shrine of the hero”. Leon saw a recess in the wall containing the relief of a youth raising a crown of olive leaves to his head – Stephanophoros, the guardian of the mints.

“That shows my occupation,” said Antikles. “But it is late and time we were all in bed. Your inn is not far from here. I hope you will call on me if you have time. Agias, light the young man to his lodging”. Wishing Leon a good night, he took a great key from his belt, unlocked his door and disappeared, while Leon followed the slave.

Next morning Leon found the ivy-wreath on the floor of his chamber. Thalia begged that she might have it. Later in the day Leon saw her in the courtyard, the wreath twined in her hair and holding a light wand, imitating a bacchanal. Once she made a swoop at her small dog, which was regarding her apprehensively. He fled from her with a yelp of terror, his tail between his legs.

To read chapter six click on this picture.