By Jackie Bishop, Location Register & WATCH Researcher

Introduction

As the researcher for the Location Register, one of the University of Reading’s (UoR) research and digital humanities projects, I identify literary manuscripts held in British and Irish archives and libraries and record them in an online database. This provides literature researchers with a one-stop-shop for finding where and how to access original manuscripts. With over 500 repositories included, there is plenty of work to do! I am constantly on the watch for announcements of new literary acquisitions and the launch of catalogued collections. I was asked to investigate manuscripts at the BBC Written Archive Centre in Emmer Green, Reading, as they had previously been researched as far back as the early 2000s.

The history of The Location Register

The original Location Register of 20th-century English literary manuscripts and letters was published in two large volumes by the British Library in 1988, edited by Dr David Sutton. This was followed in 1995 by the publication, also by the British Library, of Location Register of English literary manuscripts and letters: 18th and 19th centuries. The printed volumes are available in the University of Reading Library and Special Collections reading room.

Since 1998, records have been added to an online database, now hosted by UoR Special Collections. Around 3,000 literary authors of all genres, from major poets to minor science fiction writers and romantic novelists are documented. Enid Blyton, Marie Corelli and Ruby M. Ayres are included in the same way as Doris Lessing, Dorothy M. Richardson and Virginia Woolf. Find the full list of included authors, with brief biographical and archival details, here: Location Register NAL.

The obvious benefit of publishing the research online is that users can remotely search for authors and manuscripts and find out what repositories hold, access arrangements and archive call numbers before visiting in person. The database can be used to see connections between authors, their archive collections and regional literary movements.

BBC Written Archive Centre

The BBC Written Archive Centre (WAC) holds the working papers of the BBC from 1922 onwards. The background to the collection is described on a panel in an exhibition about the service: “The BBC’s mission to inform, educate and entertain has led to the accumulation of documents that showcase British culture and political history throughout the 20th century and beyond”.

The BBC WAC holds 4.5 miles of material, 250,000 files of correspondence and 21,000 reels of microfilm. The collections main file series are scripts, contributor files, production and policy files, and BBC publications, such as the Radio Times. More information is available on the BBC WAC website.

Caversham Park

The BBC’s documents were originally held in the Historical Records Office, which was set up in London in 1957. In 1970, the Written Archives Centre was established and the Corporation’s records were transferred to Caversham, Reading.

The BBC WAC is next door to the former BBC Monitoring mansion building and the grounds of Caversham Park. Based in Emmer Green, a quiet village with a duck pond, BBC Monitoring was a buzzing, thriving global news operation in the “big park” from 1943 to 2018. I was lucky enough to work there in the 1990s and 2000s.

Set up in 1939 before World War II, the government asked the BBC to monitor the use of the media by Axis powers, especially radio. Through the decades, the BBC monitored and translated global media coverage during historic events such as the Cold War, the fall of the Berlin wall, wars in the Gulf, Iraq and Afghanistan, terrorism, 9/11 and many more. A history of Caversham Park by Brian Rotheray (published by BBC Monitoring) covers the use of the building from the 13th century on.

Research guidance

As the BBC WAC only has a partial online catalogue, visiting in person is essential. My starting point for the project was to find out what collections and resources were available at the archive.

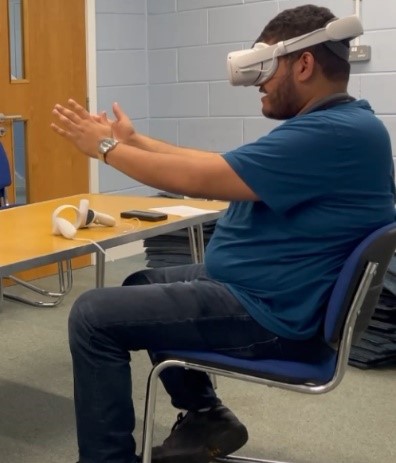

There is plenty of advice on the WAC website, with information for visiting researchers which guides you through the procedures for making an appointment, using the reading room, on site facilities, copying and licensing. There is also a research guide on how to access the material held at WAC, whether you are searching for a person, programme or policy. There is a comfortable break room with a friendly atmosphere where you can talk to other researchers. The usual reading room rules of no pens or bags applies.

The reading room is open for visitors on Wednesdays and Thursdays by prior arrangement only.

Catalogue

The BBC has a partial catalogue on The Archives Hub. This gave me an idea of the structure of the collection, extent and dates.

Material less than seven years old, material that has not yet been deposited with BBC Archives, material held for legal or business reasons or in electronic formats is not in scope for general research.

I emailed the team at WAC, explaining about the Location Register and the kind of manuscripts I was hoping to find. They suggested series of radio and TV contributor files that would be worth pursuing and offered to pick some sample files. At this stage it was hard to gauge how many files would be relevant and how many visits I would need to make. I booked a desk for two days in September 2024. Little did I know I would be visiting twice a month until June 2025!

The hunt for manuscripts

I was greeted on my first visit by a pile of around 60 files waiting for me in a trolley. The archivist assigned to help me with my research had produced a good range of different files from radio and TV contributors and talked me through the selection. There were well-known BBC names, such as Spike Milligan, Alan Bennett and Raymond Briggs.

The paper catalogues for the collection are available in the reading room so after I had looked at the initial set of files, I was able to check one of the catalogues against the list of 3,000 literary authors I was looking for. I was delighted to find so many of the relevant authors listed in the BBC catalogue.

I created a spreadsheet of existing entries in Location Register, files I had requested, which ones were open and which ones contained manuscripts. As some files were closed, I started to request more than I could get through in one sitting to compensate. It became clear quite quickly that there was a huge number of manuscripts from the 1960s onwards that had not previously been included in the Location Register.

I started looking through the files, turning every page looking for the handwriting and signatures of authors, documenting my finds and notes in a word file. What emerged was a picture of the relationship BBC staff had with literary authors, encouraging them to create for broadcast, to participate in programmes and some rejection letters. There were many legal forms covering copyright, meticulously laid out and kept. Some of the interesting files covered the whole production process for a programme, including scripts, outlines, characters, casting and finances.

In between visits, I formatted my research notes in the house style of the Location Register and input the data online. Of the 500 files I ordered over the ten months of the project, I looked at 355 files which were open for access.

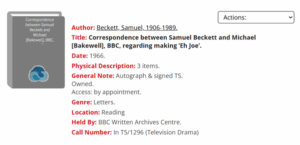

I was pleased to find some Samuel Beckett manuscripts as UoR Special Collections includes the Beckett archive. Other highlights were Denis Potter’s staff file, Spike Milligan’s correspondence in his unique and amusing style, extracts of John Le Carré material for scripts, well over 200 items of correspondence between the BBC and Alun Owen (prolific Welsh playwright, screenwriter, known for writing The Beatles’ film A Hard Day’s Night), over 300 items of correspondence between the BBC and Gwyn Thomas, a Welsh writer and broadcaster. A personal highlight was reading Sue Townsend’s correspondence about televising The diary of Adrian Mole.

There are now around 1,300 entries for the BBC WAC in the Location Register, which you can see here. As much of the BBC material is not available in an online catalogue, the archive team can now point literary researchers to the Location Register to find call numbers online prior to visiting.

Conclusion

I thoroughly enjoyed researching this well organised, fantastic resource. It is a rich collection of 20th century broadcasting, demonstrating the engagement BBC staff had with many authors.

The archive team were incredibly helpful and dedicated in helping me with my research. Thanks go to the BBC’s Sam Blake and Tom Hercock, who produced hundreds of files for me, and the reading room team for answering my many questions.

The Location Register has been regularly supported in its research by the British Academy, and since 2003 has been recognised with the status of Academy Research Project (ARP). Funding for the project has been received from the British Academy, the Strachey Trust, the Arts Council of England, the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation and the Pilgrim Trust.

GIF created by Cate Cleo Alexander

GIF created by Cate Cleo Alexander

Screenshot of an AI-generated “modernized” woman from

Screenshot of an AI-generated “modernized” woman from  Screenshot from

Screenshot from

Custom imagery for the DH Hub

Custom imagery for the DH Hub

‘

‘