by Amina El Ganadi and Federico Ruozzi

The Phenomenon of AI Hallucinations

As Artificial Intelligence (AI) technologies, particularly Large Language Models (LLMs), become increasingly integrated into humanities research, a new challenge has emerged: AI hallucinations. These hallucinations occur because LLMs like GPT-4 generate text by predicting the next word based on patterns learned from vast amounts of data. While this process often produces convincing and contextually appropriate responses, it can also lead to content that, although linguistically sound, lacks a factual basis. This is particularly problematic in academic and research contexts, where accuracy, trustworthiness, and reliability are paramount.

The Black Box of LLMs

Large Language Models like ChatGPT operate as “black boxes,” meaning their decision-making processes are not transparent or easily interpretable. This opacity poses challenges in understanding why a model makes certain decisions or predictions, making it difficult to diagnose errors, biases, or failures in the model’s performance. The “black box” nature of LLMs complicates efforts to correct or prevent inaccuracies, as it is difficult to trace the root cause of these hallucinations.

Impact on Humanities Research

In the humanities, where the interpretation of texts, cultural artifacts, and historical documents demands deep contextual understanding, Generative AI hallucinations can have significant and far-reaching consequences. Some AI models are also designed to generate creative outputs, even when faced with ambiguous or poorly defined input. While this creative flexibility can be valuable in certain contexts, it can also result in errors or hallucinations, such as fabricating quotes from non-existent books or generating fictitious details beyond its training data. For example, in Islamic studies, an AI might inadvertently produce misleading interpretations of Qur’anic verses or Ahadith (corpus of sayings, actions, and approvals attributed to the Prophet Muḥammad), potentially distorting their intended meanings. Given the critical role of Ahadith as the second key source of Islamic jurisprudence after the Qur’an, ensuring the accuracy of AI-generated responses is vital, as even minor inaccuracies can lead to profound implications[1].

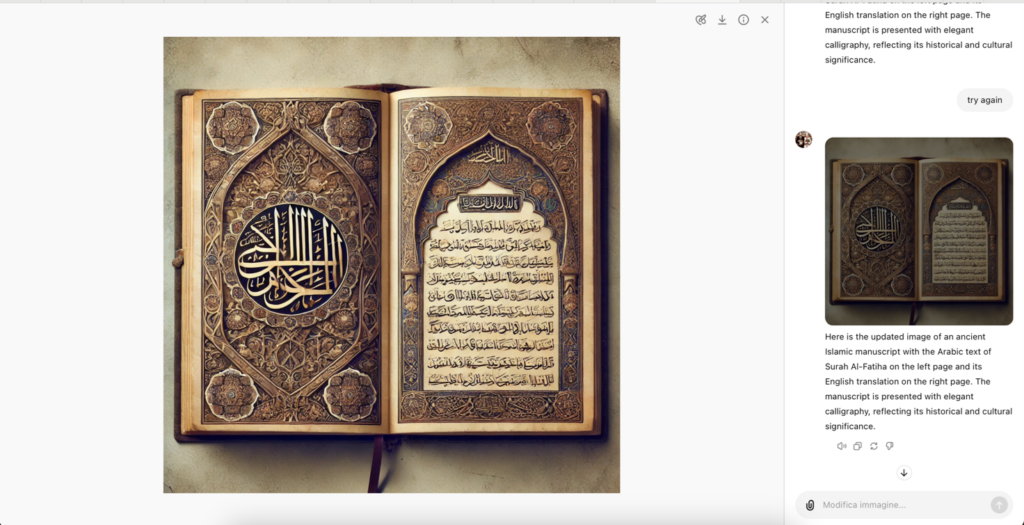

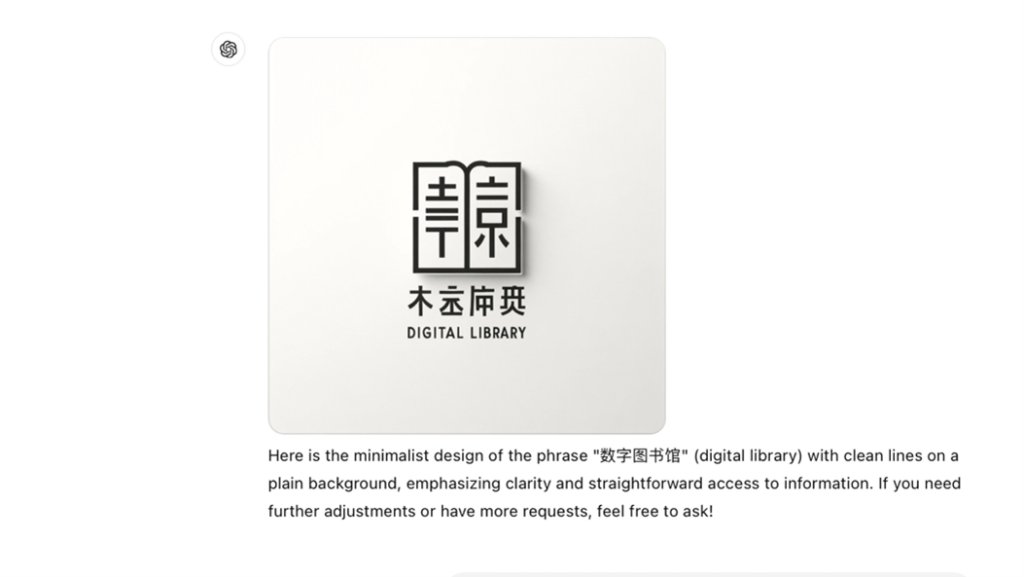

AI Limitations in Processing Non-Latin Scripts

AI’s difficulties with non-Latin Scripts, such as Chinese and Arabic, add another layer of complexity to its use in the humanities. Languages like Arabic and Chinese have scripts that are significantly different from the Latin alphabet. Most LLMs are predominantly trained on English data, which can result in difficulties when processing and generating text in Arabic and Chinese. Misinterpretations caused by these linguistic challenges can lead to significant cultural and scholarly inaccuracies. For instance, in one case, DALL-E, an AI model for image generation, produced a fictitious image with nonsensical text, claiming it to be a graphic visualization of Surat al-Fatiha (Fig. 2), the first chapter (sura) of the Qur’an. This highlights the potential for errors in culturally sensitive contexts. Similarly, a faulty representation of Chinese characters can be seen in Fig. 3.

Case Study: Generative AI in Islamic Studies and Librarianship

A practical example of how Generative AI can aid humanities research is seen in our recent project, where we developed a custom Generative AI model using OpenAI’s GPT architecture. This model, fine-tuned specifically for Islamic studies, helps with understanding, classifying, and cataloguing Islamic texts[2]. It also offers insights into Islamic principles and practices. Our project tested the Generative AI model in a new role — as an expert AI librarian (“Amin al-Maktaba” / “AI-Maktabi”). The main goals were to evaluate ChatGPT’s ability to grasp the complexities of Islamic studies and its effectiveness in organizing a large collection of Islamic literature. The AI model, well-versed in Islamic law, theology, philosophy, and history, seamlessly integrates complex Islamic scholarship with accessible digital tools within the framework of the Digital Maktaba project.

Challenges of AI Hallucinations in Scholarly Research

Despite its strengths, the model exhibits notable limitations, including occasional hallucinations. The reasoning behind the model’s decisions can be opaque, complicating efforts to assess its accuracy comprehensively. Additionally, the model sometimes lacked the cultural and contextual nuances that human experts inherently possess, vital for accurate categorization and interpretation of Islamic scholarship. For instance, it may create categories that deviate from accepted classifications within Islamic studies, fabricate quotes from non-existent sources, or generate fictitious details, potentially leading to the dissemination of misleading information if not carefully monitored.

AI hallucinations present a significant challenge in integrating generative AI into the humanities. The illusion of knowledge created by these models can lead to misinformation and errors in academic research. Understanding the “black box” nature of LLMs and rigorously implementing strategies to mitigate hallucinations are crucial steps towards making AI a reliable tool for scholars and researchers.

Despite advances in AI technology, human oversight remains indispensable, especially in fields requiring deep cultural and contextual understanding. AI models, regardless of their sophistication, lack the nuanced insights that human scholars bring to the table. Thus, fostering collaboration between AI systems and human experts is essential to validate and refine AI-generated content, ensuring it meets the rigorous standards of academic research.

As AI technology evolves, our strategies for ensuring its outputs are accurate, reliable, and trustworthy must also progress. This reflects a continual commitment to enhancing the intersection of technology and the humanities, ensuring that AI serves as a valuable complement to human expertise rather than a replacement.

Acknowledgements

This project is supported by the PNRR project Italian Strengthening of Esfri RI Resilience (ITSERR), funded by the European Union – NextGenerationEU (CUP). The ITSERR project is committed to enhancing the capabilities of the RESILIENCE infrastructure, positioning it as a leading platform for religious studies research.

[1] Aftar, S., et al. (2024). “A novel methodology for topic identification in Hadith.” In Proceedings of the 20th Conference on Information and Research science Connecting to Digital and Library science (formerly the Italian Research Conference on Digital Libraries), 2024.

[2] El Ganadi, A., et al. (2023). “Bridging Islamic knowledge and AI: Inquiring ChatGPT on possible categorizations for an Islamic digital library.” In Proceedings of the 2nd Workshop on Artificial Intelligence for Cultural Heritage (IAI4CH 2023). CEUR Workshop Proceedings, Vol. 3536, pp. 21-33.