In the summer of 1882, reports began to circulate in British newspapers of “The Egyptian Crisis”. A nationalist movement led by Colonel Ahmed ‘Urabi was fighting increasing European financial and political incursion into Egypt. Alexandria, a key port-city on Egyptian coast, was the focus of British forces’ initial bombardment. The result, by the end of 1882, was Britain’s occupation of Egypt.

After that, British officials worked in Egyptian government departments. British investors and engineers continued colonial infrastructure projects that changed Egypt’s landscape. Anglo-Egyptian military campaigns brought Sudan, Egypt’s southern neighbour, into British colonial administration by the century’s end. But British involvement in Egypt did not only take political and military form. It involved culture too – particularly Egypt’s ancient monuments and artefacts.

From the 1880s, increasing numbers of British tourists and British archaeological teams went to Egypt during its ‘winter season’ (November to March), joining a growing British residential community.

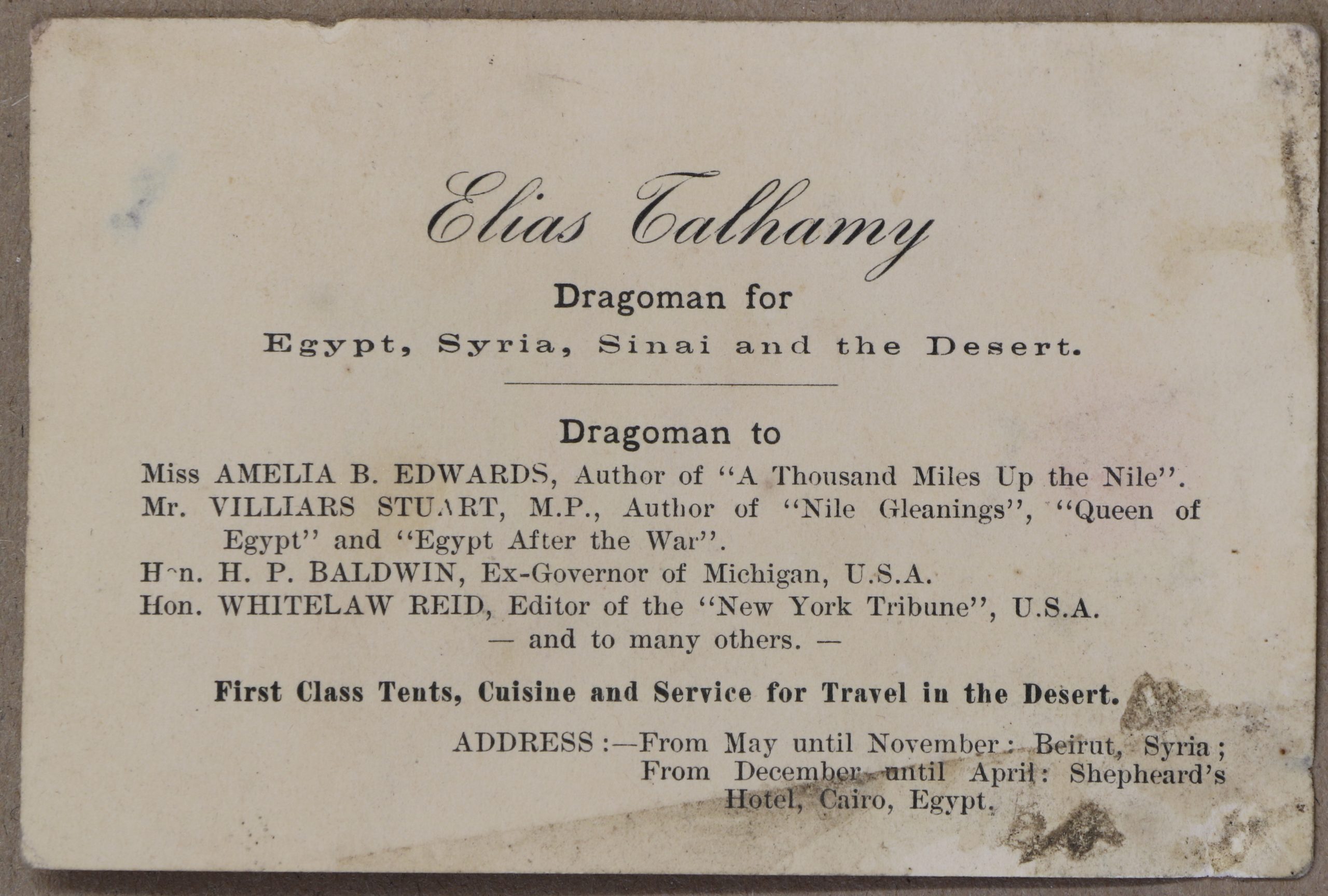

By rail and river, often courtesy of Thomas Cook & Son, British tourists, including George William Palmer of Huntley & Palmers Biscuit company in Reading, flocked to see Egypt’s archaeological sites. They were conducted around the sites by Egyptian dragomen like Elias Talhamy, and they carried guidebooks that charted ongoing excavations and discoveries. A few of them, including Henrietta Lawes of Caversham, were also there as students or volunteers on excavations.

British archaeologists were given permits to excavate by the European-controlled Egyptian government. The archaeologists employed Egyptian workers to do back-breaking labour unearthing ancient cities and temples, houses, graves and artefacts.

John Garstang was one of these archaeologists.

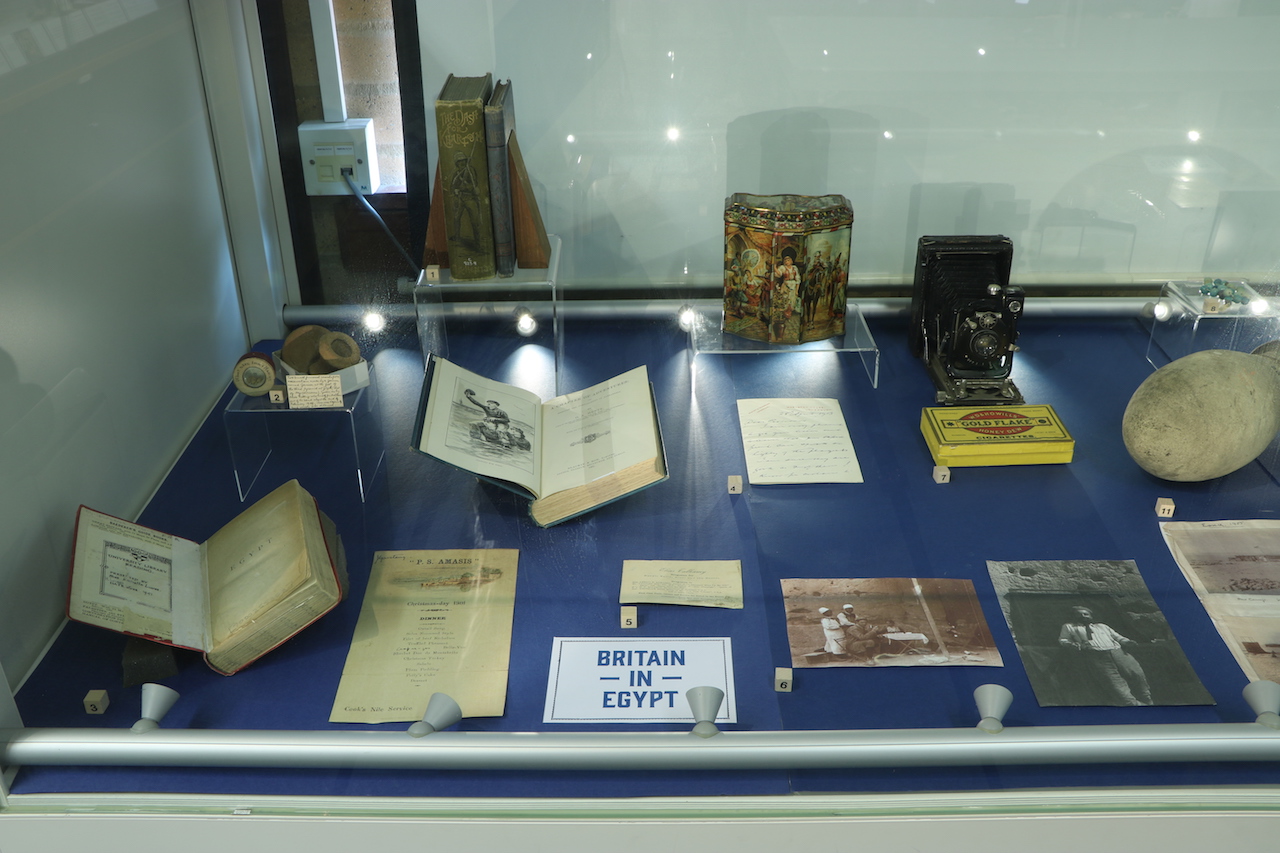

On display

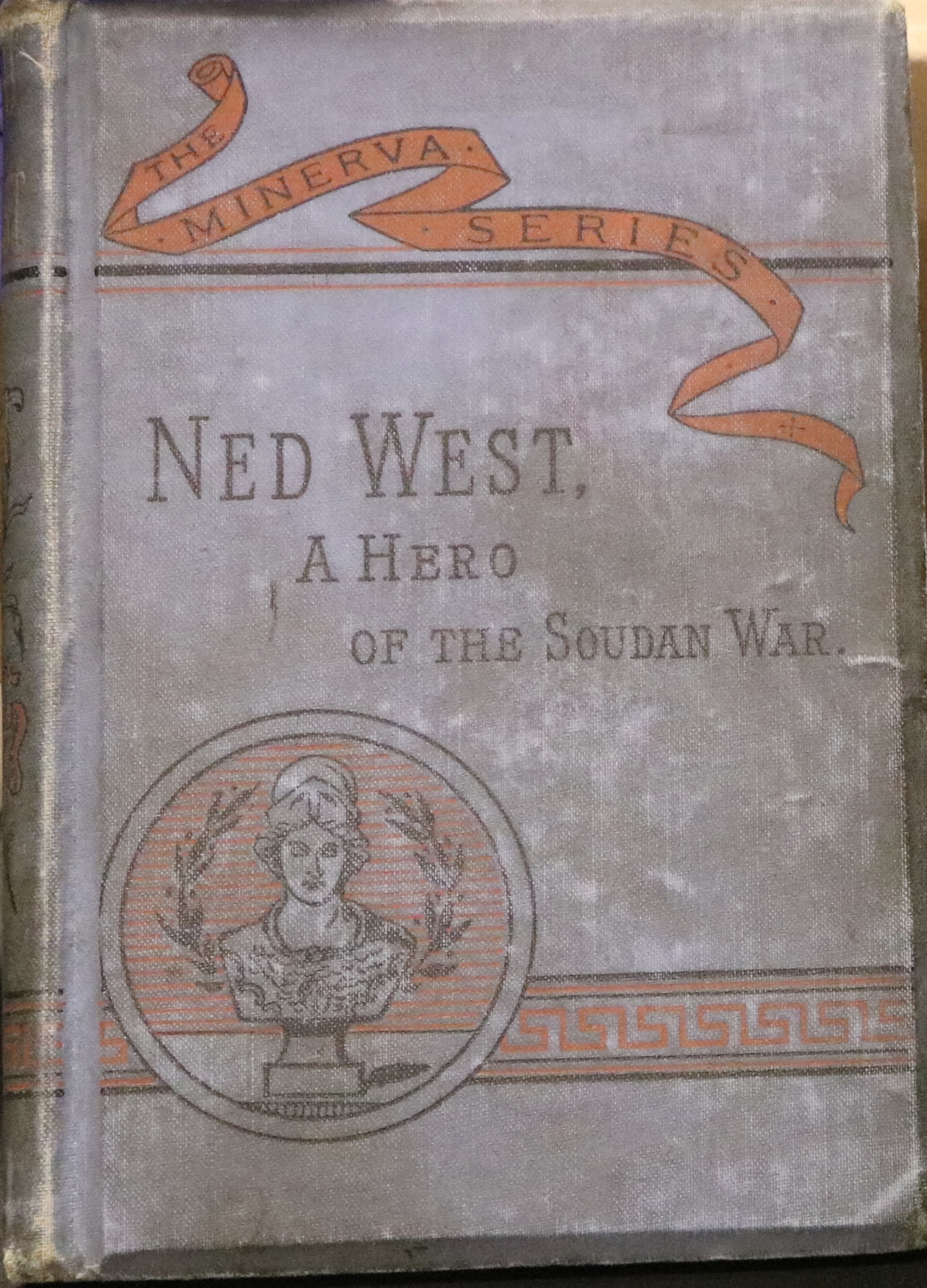

- Books on the Egyptian & Sudan campaigns written for children in Britain: G. A. Henty, Chapter of Adventures: or, Through the Bombardment of Alexandria (1891) and Dash for Khartoum (1892), Robert Hind, Ned West: A Hero of the Soudan War [on loan from the Children’s Collection, University of Reading Special Collections].

-

- Learn more about the modern history of Egypt in this audio with Dr Dina Rezk.

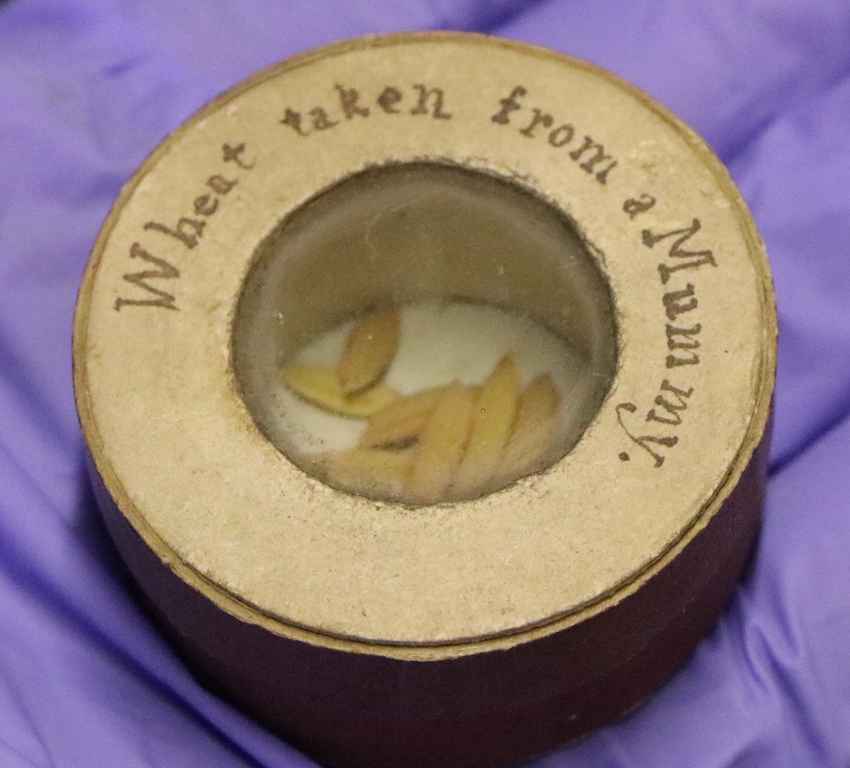

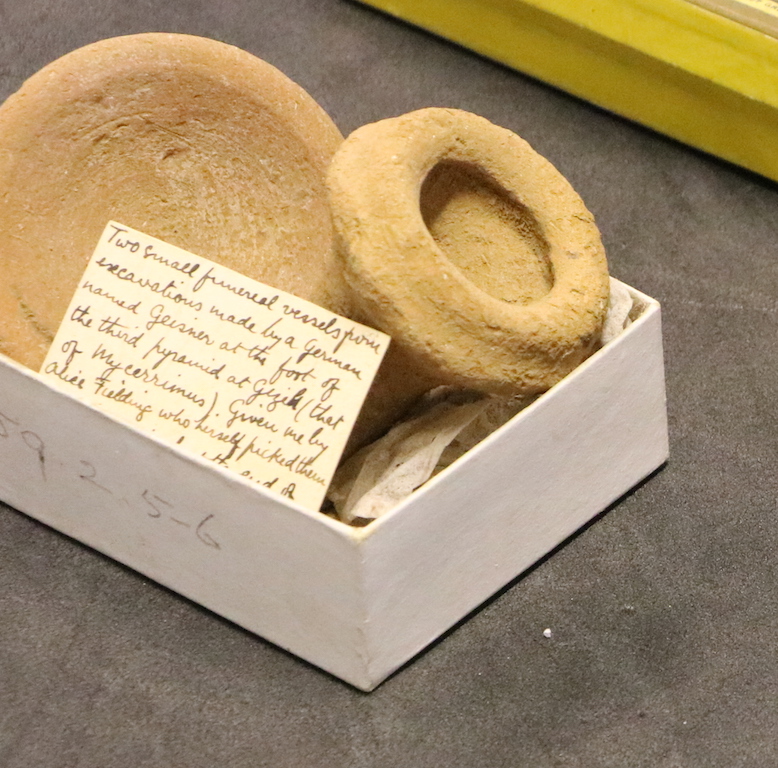

- ‘Mummy wheat’ made for tourists, possibly from a trip to Egypt in 1902. The grains inside the box are actually rice. Two ancient miniature pots said to be from Giza, with a label indicating they were “picked up” during excavations in 1908 and brought back to Britain by a Miss Alice Fielding [Ure Museum].

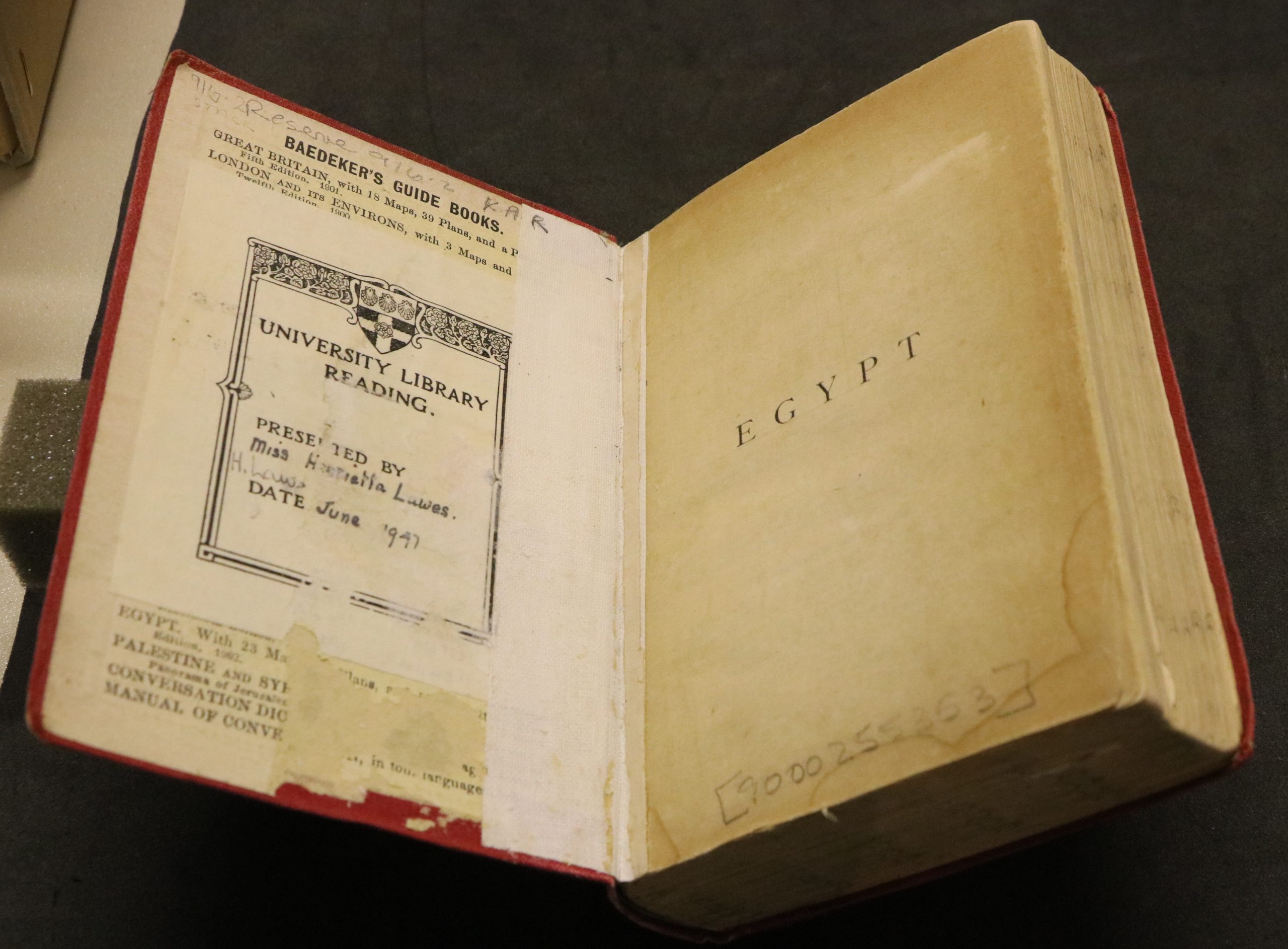

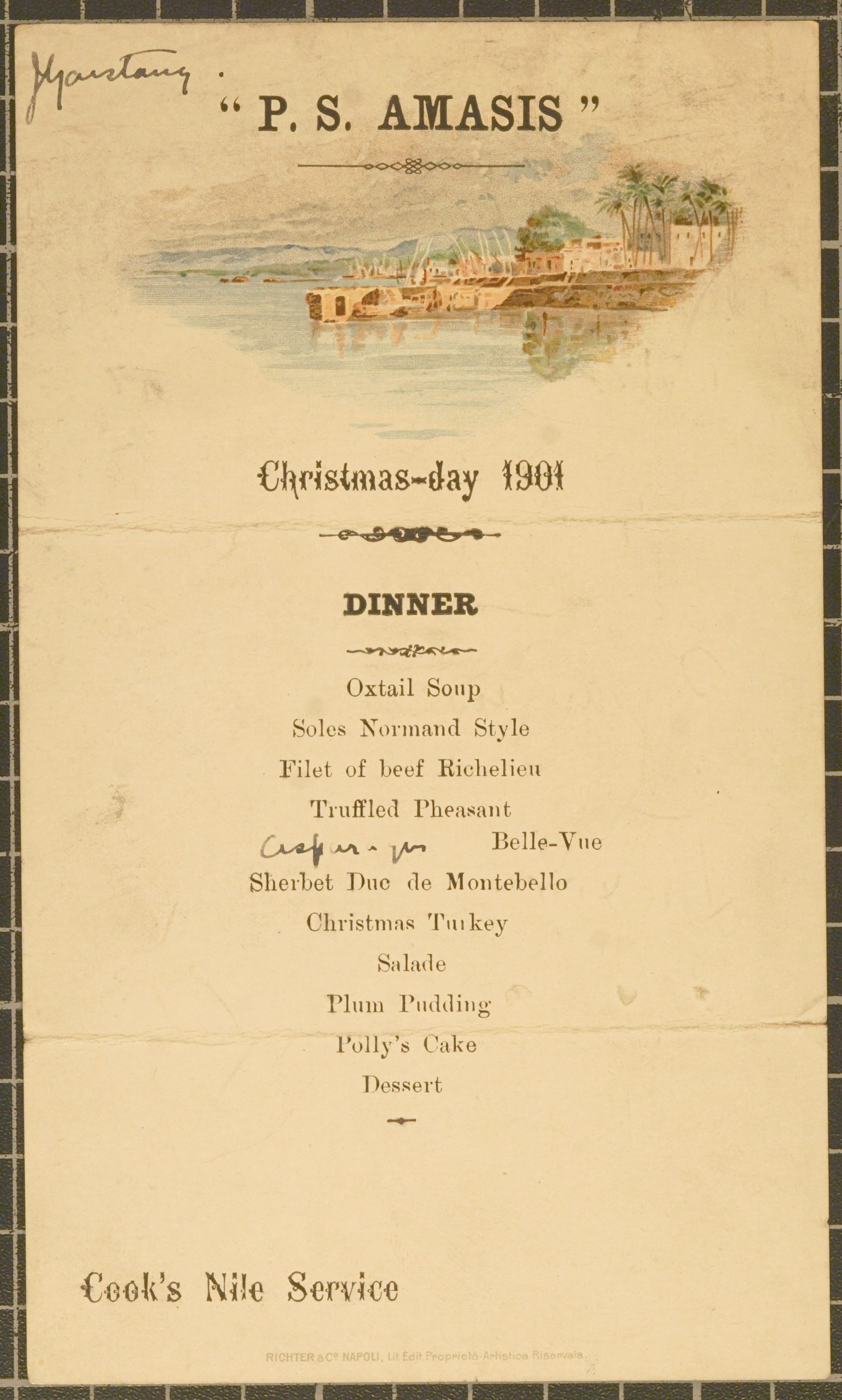

- Karl Baedeker, Egypt: a handbook for travellers (1902) from the bequest of Henrietta Lawes – artist, archaeologist, and Ure Museum donor [on loan from University of Reading Special Collections]. Baedeker guidebooks were used by many tourists to Egypt, and were particularly famous for high quality maps. Menu for Christmas Dinner attended by John Garstang on Cook’s Nile Steamer, “P. S. Amasis”, 1901 [Reproduced courtesy of Garstang Museum].

-

- Learn more about Henrietta Lawes in this blog post.

- Learn more about tourism to Egypt in this audio, an interview with Professor Rachel Mairs.

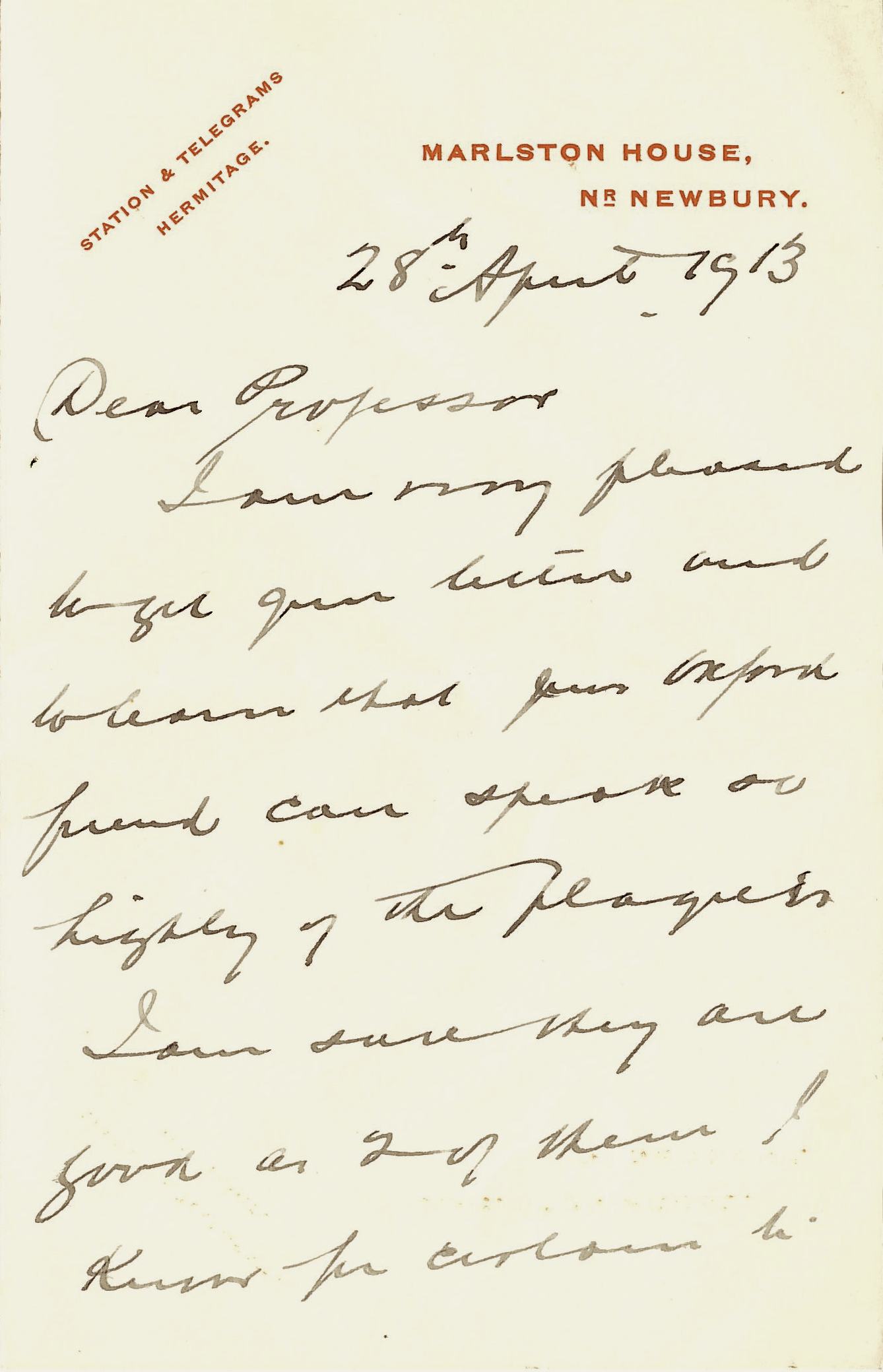

- Letter from George William Palmer of Huntley & Palmers to Percy Ure [Ure Museum]. The letter relates to “plaques” (casts) of wall reliefs from the mortuary temple of Hatshepsut, a famous 18th Dynasty female pharaoh, at Dier el-Bahri. Palmer may have purchased these during a trip to Egypt with his wife Eleanor in 1903. Two are now on display in the Ure Museum. Huntley & Palmers biscuit tin featuring scenes from the Arabian Nights stories [on loan from the Museum of English Rural Life]. The imagery on the tin reflects Western views of an ‘exotic East’. The tin was made in 1894.

- Business card for Egyptian dragoman Elias Talhamy, late 19th century [on loan from Rachel Mairs]. It shows key clients, and advertises that he worked in both Egypt and Syria.

-

- Learn more about dragoman business cards in this film, and more about the lives and experiences of dragomen in this audio, both interviews with Professor Rachel Mairs.

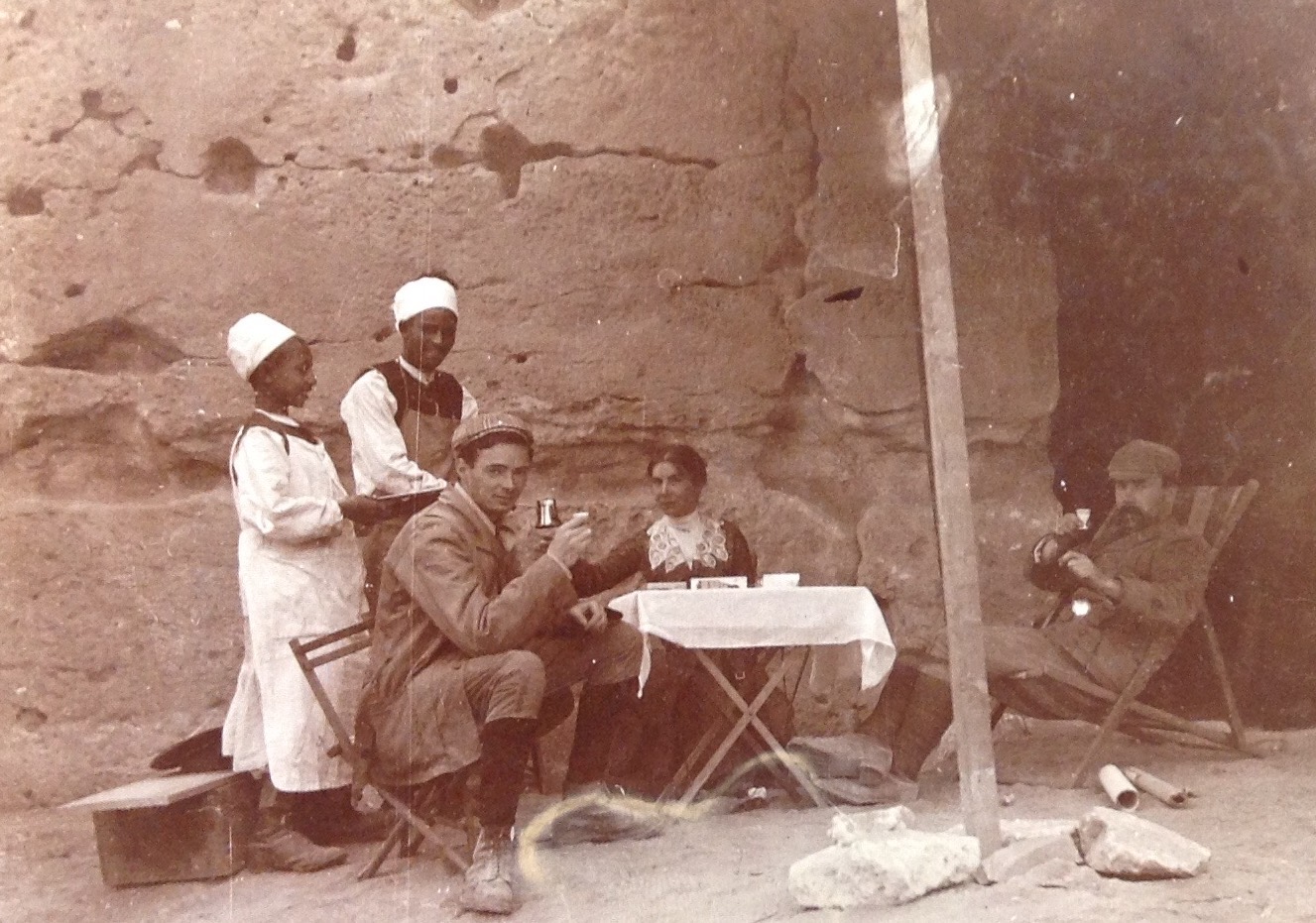

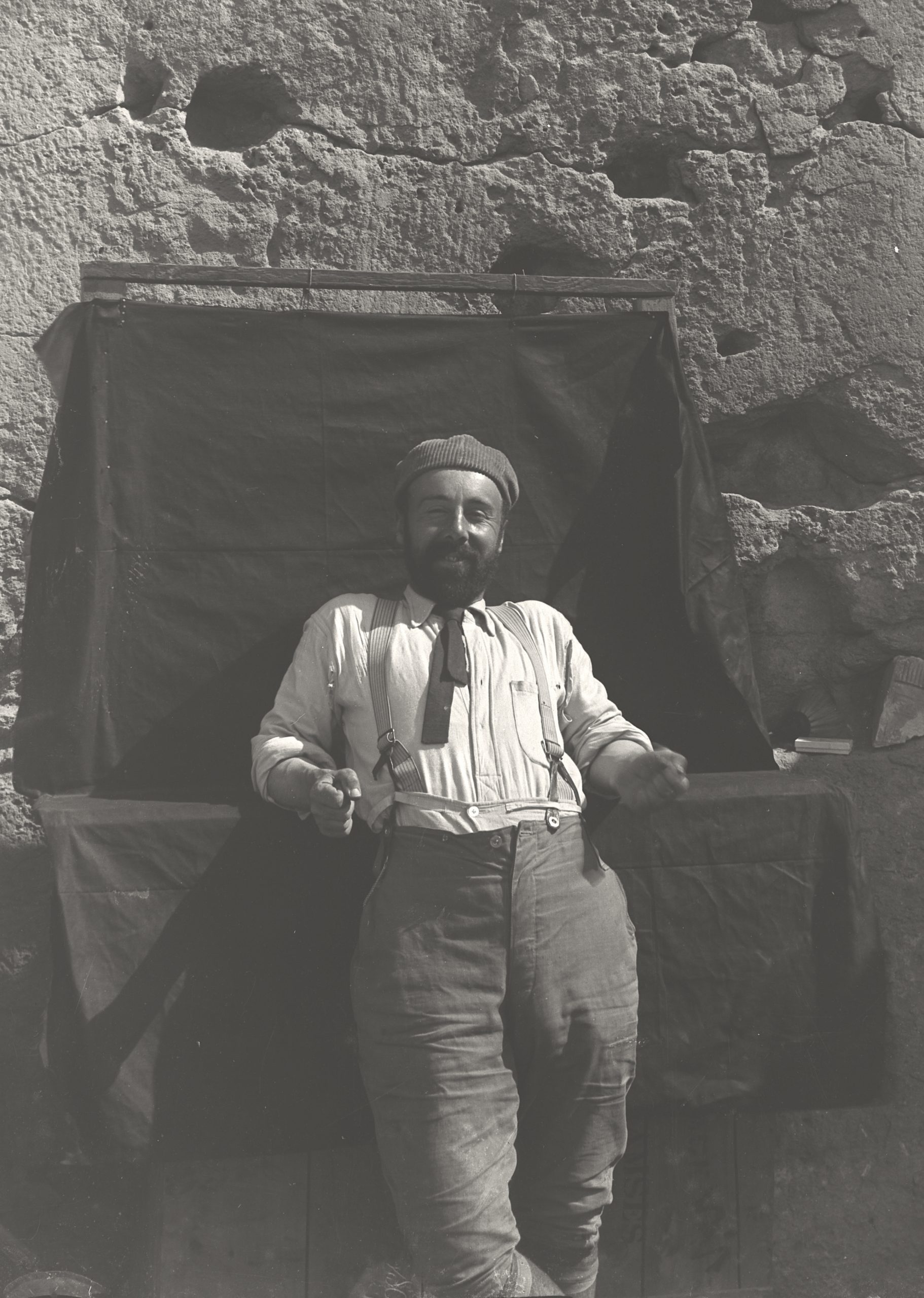

- Photograph of (L-R) two unnamed Egyptians waiting on Garstang’s assistant Harold Jones taking tea with a woman visitor identified as Miss S and John Garstang. In a “Copy of Agreement”, the contract between Garstang and his financial backers (“Excavation Committees”), money was available for him to employ servants on site. Photograph of John Garstang at Beni Hasan, c. 1902-04 [Reproduced courtesy of the Garstang Museum].

7. Archaeological equipment: camera and cigarette box [Ure Museum]. A camera was an essential tool for recording excavated sites and artefacts. As many archaeologists were smokers, cigarette boxes were often re-used for holding small artefacts.

-

- Learn more about the legacy of colonial archaeology in modern Egypt in this audio with Dr Dina Rezk.

Go to Britain in Egypt Drawer.

Move on to next section, Excavating Egypt

Text and labels by Amara Thornton (Research Officer, Ure Museum)