Western archaeologists digging in early 20th century Egypt had to get permission from the Egyptian Government. The permits issued stipulated that artefacts uncovered during excavations had to be divided with the Egyptian Government, a system known as partage. Antiquities Inspectors would decide which artefacts would remain in Egypt, and which could be taken out of the country.

Under this system, John Garstang was able to keep a portion of the artefacts discovered during each season he was in Egypt. The artefacts were transported back to Britain, and put on display for a few weeks in June/July. During his time excavating in Egypt, he exhibited in various locations, including Liverpool and Oxford, as well as London. At this time of year, many wealthy and well-connected people were in London for the annual summer ‘Season’ (May-July).

After the exhibitions closed, artefacts would be divided among the members of Garstang’s “Excavation Committees”. Some artefacts went straight into museum collections in Britain; others remained in private hands for a time. The Institute of Archaeology in Liverpool also retained some artefacts for its own Museum. It is now called the Garstang Museum.

By the early 1920s, John Garstang was no longer excavating in Egypt. Based mainly in British Mandate Palestine at this time, Garstang instructed colleagues at the Institute of Archaeology to begin selling antiquities in the collection.

Percy Ure purchased a selection of Egyptian antiquities from Liverpool for the newly opened Museum of Greek Archaeology in 1923. The Institute of Archaeology’s Secretary Meta Williams (whose brother was Professor of Bacteriology at Reading) helped to catalogue these antiquities.

Egyptian students had been coming to study at University College Reading for over a decade by the time the Liverpool collection was acquired.

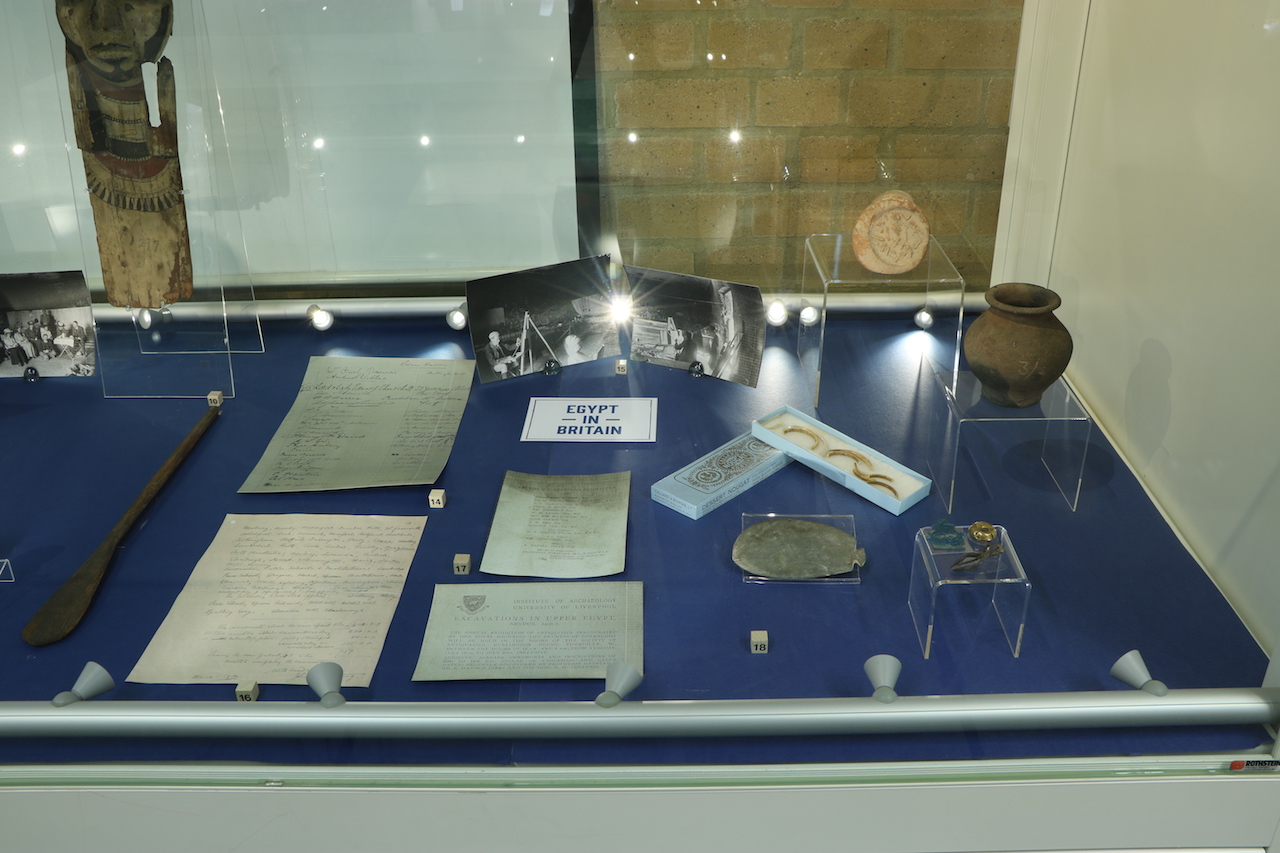

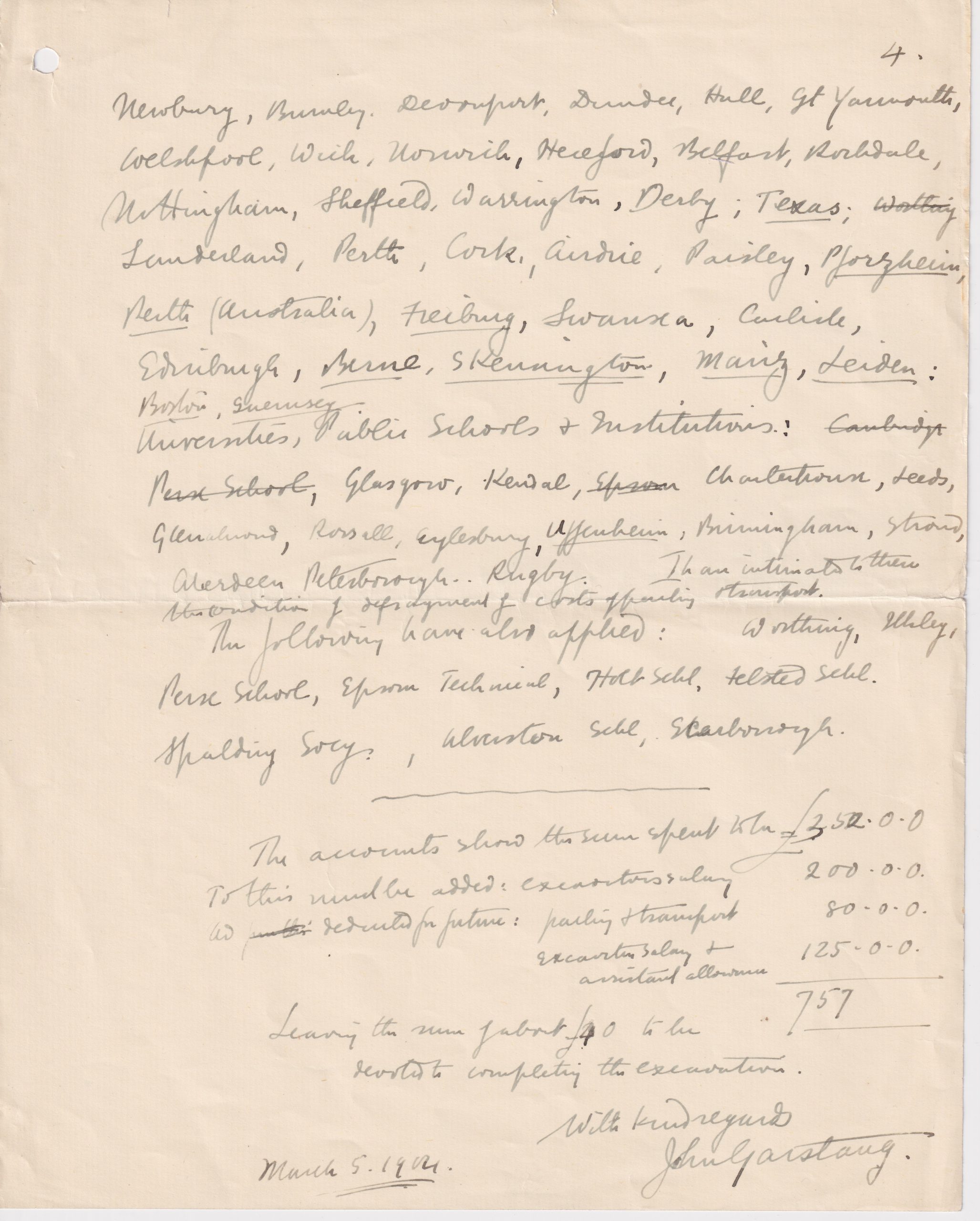

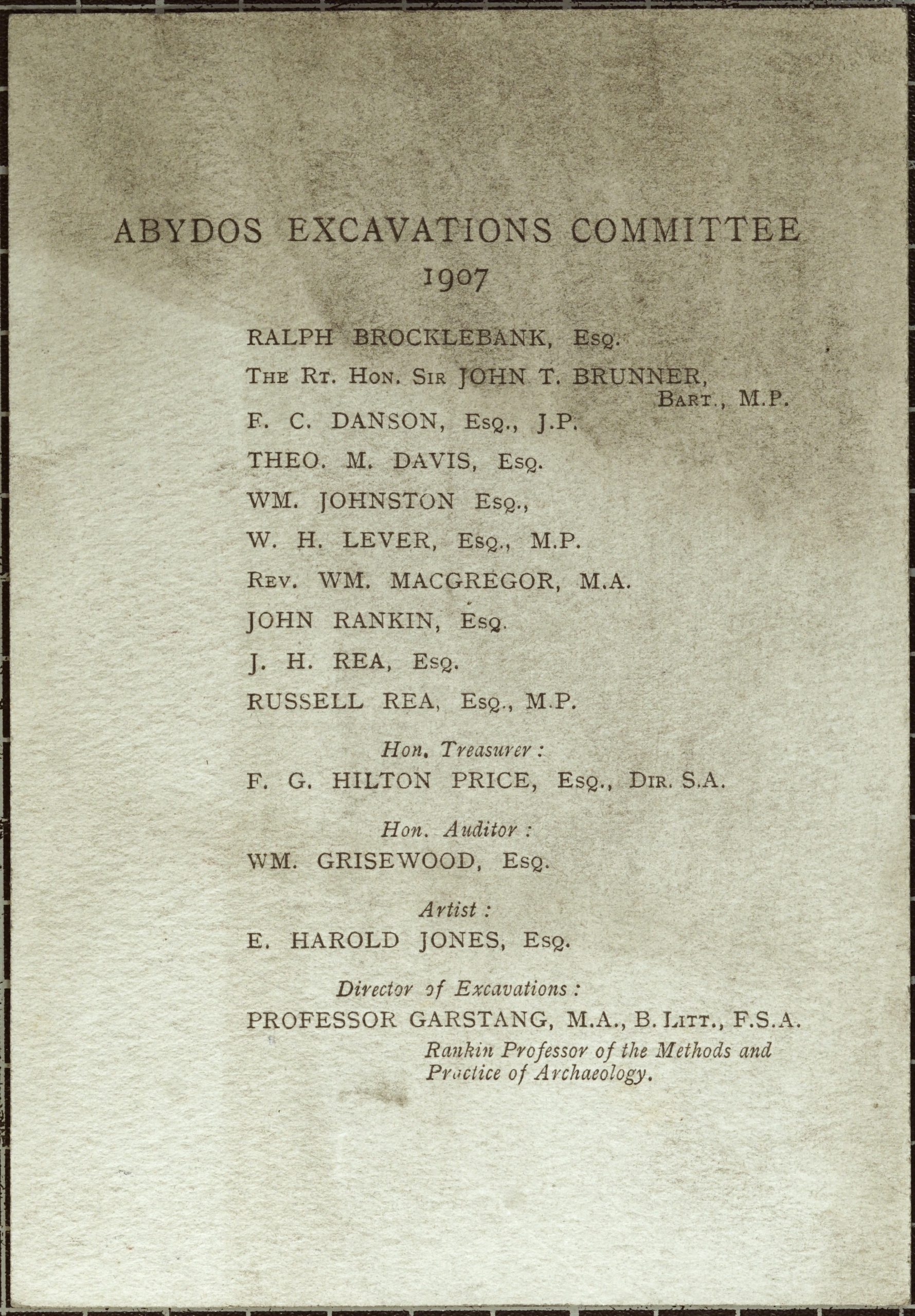

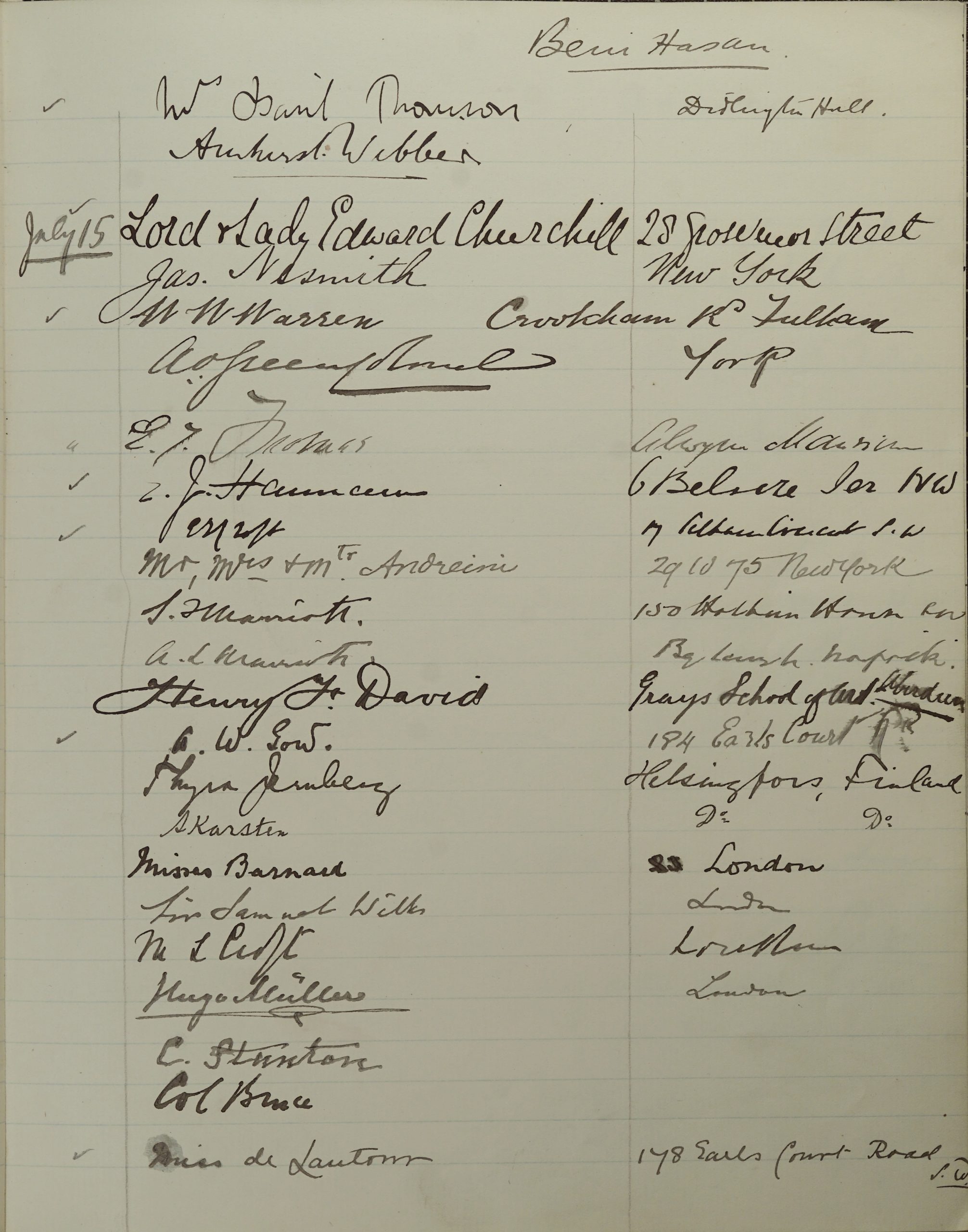

On display in the case

- Page from one of John Garstang’s final interim field reports from excavations at Beni Hassan in 1904 showing institutions requesting antiquities from Beni Hassan [Reproduced courtesy of the Garstang Museum]. The “Beni Hasan Excavation Committee” decided to offer antiquities to a range of institutions, as long as the institutions applying were open to the public. They placed advertisements in local newspapers to promote the scheme. The institutions listed here include museums and educational institutions across the UK, Europe, the United States and the British Empire.

- Printed list of the members of Garstang’s Committee for excavations at Abydos, 1907 [Reproduced courtesy of the Garstang Museum].

- Page from the visitors’ book to the first exhibition of antiquities from excavations at Beni Hasan, showing visitors for 15 July 1903. The display was held at the Society of Antiquaries, abutting the Royal Academy in Burlington House in London over two weeks in mid-July. It was open for a few days for a “private view” before the formal “inauguration”. Printed invitation to the exhibition of antiquities from Abydos held at the Society of Antiquaries, London, in July 1907 [Reproduced courtesy of the Garstang Museum].

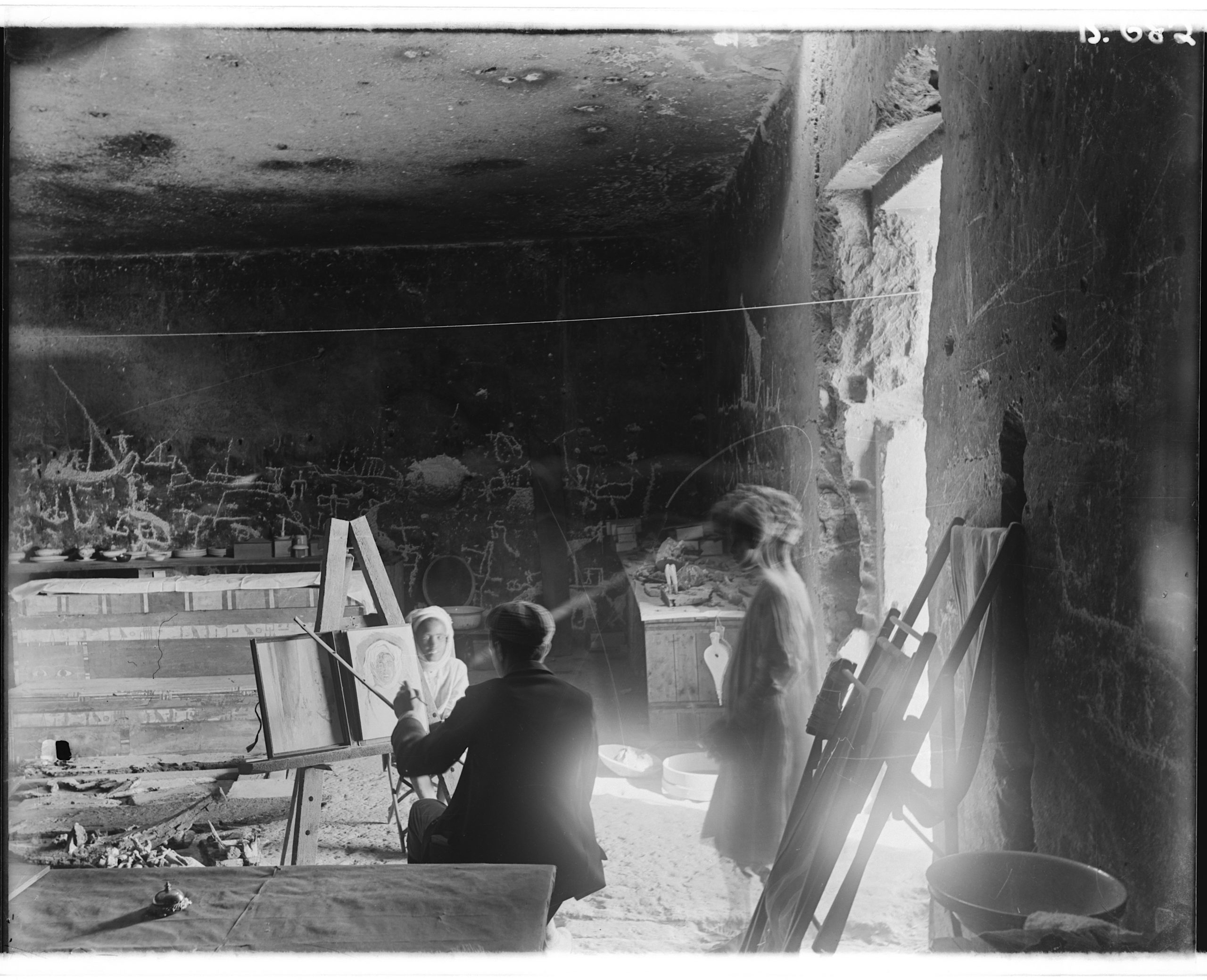

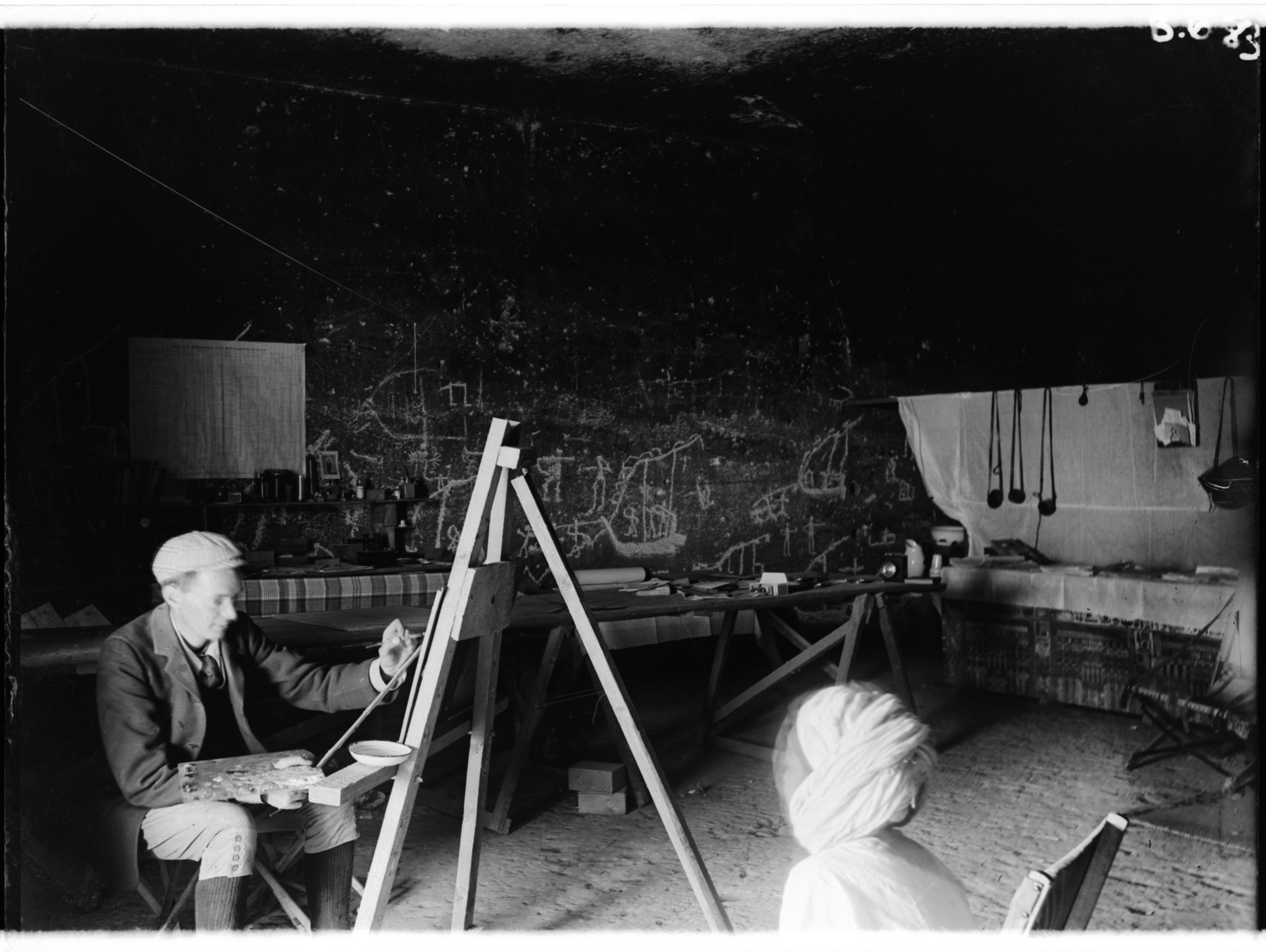

- Photographs of Harold Jones painting a portrait of one of the workmen on site at Beni Hasan [Reproduced courtesy of the Garstang Museum]. Jones’s letters from Beni Hasan show that he painted portraits of Saleh Abd El Nebi and two other workmen: Abadi and Mahmoud. The sitter in this photograph is either Abadi or Mahmoud. These portraits and other works by Jones were displayed alongside antiquities in the Beni Hasan exhibition in 1904. One of Jones’s paintings was given as a gift to Princess Henry of Battenburg. Jones was battling tuberculosis while excavating with Garstang. He died from the disease in 1911.

-

- Antiquities from Liverpool not definitely assigned to particular sites: funerary cone (18th dynasty) with a label indicating it was originally part of the private collection of James Grant, physician to the elite families of Cairo; fragments of shell and bone or ivory bracelets (Predynastic), kept in a fancy nougat box; fish shaped slate palette (Predynastic), used for grinding makeup; blue glazed faience amulet in the shape of Bes, Egyptian god of the household (Late Period); gold plated hair ring (23rd Dynasty). Percy Ure bought £20 worth of antiquities from Liverpool to use in teaching at University College Reading. He had a list of items he wanted, but what was sent from Liverpool did not wholly match this list.

Go to Egypt in Britain Drawer.

Go back to the previous section, Excavating Egypt.

Text and labels by Amara Thornton (Research Officer, Ure Museum)