By Amy C. Smith (Curator, Ure Museum)

Through her explorations in the archives at the Ure Museum & elsewhere, Amara Thornton helped us to (re)write the history of the Ure Museum (see e.g. An interwar interdisciplinary vision). While the basic history—that its collections were brought together by a pioneering husband & wife team, Annie & Percy Ure—is basically sound, the details of the Ures’ lives & work, especially those of Annie, had barely been written let alone understood. Writing Annie’s history is a longer-term project that has begun to be ably tackled by Ruth Lloyd, both through her Trowelblazers article and with the booklet, Annie Dunman Hunt Ure, 1893–1976, now downloadable from our new webpages, collections.reading.ac.uk/ure-museum/learn. Now that the door has been opened, however, we have found so much more to be studied, understood and written about our recent history.

Before the Ure Museum of Greek Archaeology (originally Museum of Greek Archaeology) came into being, University College Reading had a short-lived Museum of History and Archaeology that unified archaeological remains of Mediterranean and other cultures, notably artefacts from Donald Atkinson’s 1914 excavations at Lowbury Hill, even a pair of Anglo-Saxon skeletons displayed in a double-decker case. By the early 1920s, however, the antiquities were divided and the Lowbury finds played their part in the Romano-British Museum, then in Reading’s History Department. By the 1970s these finds devolved to the Archaeology Department and finally dispersed. So went the history—at least in the 20th century—of academic specialisation and institutional siloing of artefacts, information and knowledge. Just as it is impossible for us to study the ancient Greeks without the Romans, or vice versa, it is a mistake to learn about ancient histories without consideration of the modern histories that have shaped our perceptions of antiquity. As for archaeologies, I share with Annie Ure—who as a University of Reading student was inspired by the excavations at Lowbury Hill (see On museum beginnings)—an enthusiasm for archaeological sites, whether or not they pertain to the ancient Greeks on whom my academic writings tend to focus.

Last year, together with Amara & other colleagues, I went in search of Lowbury Hill and its now dispersed antiquities. Alongside the 2nd-century AD Roman-Celtic temple (Fulford & Rippon 1994), Atkinson had found the barrow burial of an Anglo-Saxon chieftain—Mr Low, as Annie Ure (and therefore I) call him—with all his gear. (The hill’s name actually comes from old English hlaw-burgh, meaning ‘barrow by the enclosure’.) Mr Low, a complete ‘Vatcher’ type Anglo-Saxon (7th century) warrior, was recently restored to his former splendour at the Oxfordshire Museum in Woodstock, in a phallocentric arrangement that apparently replicates his original deposition.The female skeleton hitherto displayed alongside him in Reading’s Museum of Archaeology remains in boxes, shelved at Oxfordshire County Council’s Museums Resource Centre. Like so many women who occupied the limelight briefly in the earlier 20th century, she’s all but forgotten, seemingly not for the first time, yet might someday reveal her own hidden histories.

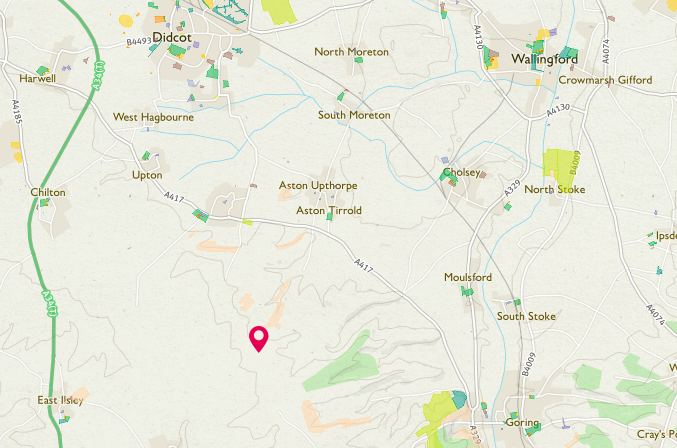

And what of the site itself? Annie & her fellow students had cycled to Lowbury from Cholsey Station, via the Fair Mile, still a byway. When I walked this route with Amara & other colleagues on a beautiful Spring day last year, our explorations were brief, but the hill exceeded my expectations and beckoned me back. During COVID19-induced lockdown, my ‘Boris walks’ helped me reconnect with nature and history, and I eventually approached Lowbury Hill from the Ridgeway, which runs just south of it. Because of the adjacent farm, at a similarly high elevation, Lowbury Hill (at 186m, the highest point of the eastern Berkshire Downs) comes into focus quickly at the top.

Writing back in 1994, Heinrich Härke complained that “the view from the closest valley sites to the barrow location is obscured by the foothills of the Downs and even a massive barrow would have been impossible to spot with the naked eye from the Anglo-Saxon settlements along the river” (Fulford et al. 1994, 204). This perspective is true enough from the Reading / Berkshire approach but he couldn’t be more wrong if approaching from elsewhere. Lowbury Hill affords superb views across the Downs extending to the west, the Vale of the White Horse to the north-west, the Thames Valley and the Chilterns to the north-east. Likewise I have since spotted Lowbury Hill from most Anglo-Saxon sites in South Oxfordshire’s Thames River Valley, to its North and East. A sharp dropoff in the profile of the Ridgeway clearly indicates Lowbury’s western end. The barrow, especially if marked by construction or trees—two hawthorn trees currently frame the spot—thus would have been easily visible from the closest Anglo-Saxon settlements and cemeteries in the Thames Valley. Its visibility is borne out by its role as a beacon station for the 1887 summer solstice when no less than 40 beacons were lit there to celebrate Queen Victoria’s golden jubilee, according to a Victor Milward, reporting to the Times on Tuesday, Jun 28, 1887 (8). While Heinrich complained again that the Anglo-Saxon sites were far away—more than 5 kilometres—as my lockdown walks have lengthened that distance has shrunk. If the temple and then the barrow were placed on Lowbury Hill because of its high elevation, they were prominent because of the visibility of the spot, not necessarily because of its proximity to any settlements.

Who warranted such a prominent burial? Our Mr Low was clearly positioned like an Anglo-Saxon warlord, with the usual grave goods—spear, sword, shield—and indeed the barrow: the Anglo-Saxons of the 6th-7th centuries had begun to imitate this Neolithic–Bronze Age burial practice, perhaps in homage to the traditional rulers. His connection to the Romano-Celtic cultural past, however, was marked both in the positioning of his barrow alongside a typically square 2nd-century AC Romano-Celtic temple of large proportions and in his grave goods—hanging bowl and spear head—which were decorated in Romano-Celtic style with enamel. While Heinrich & the excavators preferred to see him as an Anglo-Saxon, Martin Henig has argued “it looks rather as if he wanted to make it clear that he was British” (2002, 11). The spear blade was a simple ‘C2’ leaf-shaped form that was popular among 7th-century Anglo-Saxon barrow burials (Swanton, 1974, 8; Pollington 2008, 166) so the hybridity of grave goods supports the ‘continuity hypothesis’, whereby intermarriage and trade amongst Britons, invading Saxons and others caused a blur in the distinctions between the two cultural groups (Heather, 2015, 290). Further indications of local symbiosis in the relatively peaceful 7th century might be found in place names that developed at that time, for example Wallingford, just to the northwest, whose name recalls the Welsh (thus Celts/Britons) who used/controlled its ford across the Thames.

Was Mr Low British? Skeletal analysis, specifically isotope analysis (oxygen & strontium levels), in fact, suggest this tall Caucasian male must have lived as a child at the tip of Cornwall or in western Ireland (Bryant-Buck 2013, 58, 73). Such evidence isn’t conclusive either way, but certainly encourages a nuanced reading of his origins that supports our inference of his cultural connections to the Romano-Celtic past generated from his use of enamel and his proximity to a Romano-Celtic temple.

A mixed population is also suggested by the textual sources/legends. While there is evidence of Germanic/Anglo-Saxon populations settling in the Thames River Valley from around from the 4th century AD, St. Birinus legendarily converted them to Christianity, when he baptised the King of the ‘Gewisse’, Cynegils, in 636 (Seymour 1764, 43). Mr Low was seemingly buried in the next generation: could he be one of Cynegils’ sons, Cwichelm or Cenwalh, whose name is British rather than Anglo-Saxon and again suggests a blended culture? Such blended populations with intercultural tendencies recall the need for cross-cultural and interdisciplinary archaeological and historical research as fostered in Reading’s first Museum of History and Archaeology.

References/Further Reading

Atkinson, Donald. 1916. The Romano-British Site on Lowbury Hill in Berkshire. University College Reading Studies in History and Archaeology. Reading: University College Reading.

Bryant-Buck, Harriet. 2013. A Bioarchaeological Study of Skeletal Remains from Lowbury Hill, Oxfordshire. Master’s Thesis. Cranfield University.

Fulford, Michael J. et al. 1994. A Re-Assessment of the Probable Romano-Celtic Temple and the Anglo-Saxon Barrow, Archaeological Journal 151, 158–211 (including Härke, Heinrich. 1994. Lowbury Hill: A context for the Saxon barrow, 202-206).

Heather, Paul. 2015. Empires and Barbarians: The Fall of Rome and the Birth of Europe, 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Henig, Martin. 2002. Roman Britons after 410. British Archaeology 68, 8-11.

Pollington, Stephen. 2008. Anglo-Saxon Burial Mounds: Princely Burials in the 6th and 7th Centuries. Norfolk: Anglo-Saxon Books.

Seymour, Edward, 1764. The Complete History of England 1. London.

Swanton, Michael J. 1974. A Corpus of Pagan Anglo-Saxon Spear Types. British Archaeological Reports 7. Oxford:

Williams, Howard. 2014. Exploring the Biggest Ever Anglo-Saxon Knob. Online at https://howardwilliamsblog.wordpress.com/2014/06/01/exploring-the-biggest-ever/ [Accessed 3 July 2020]