By Amie Bolissian-McRae

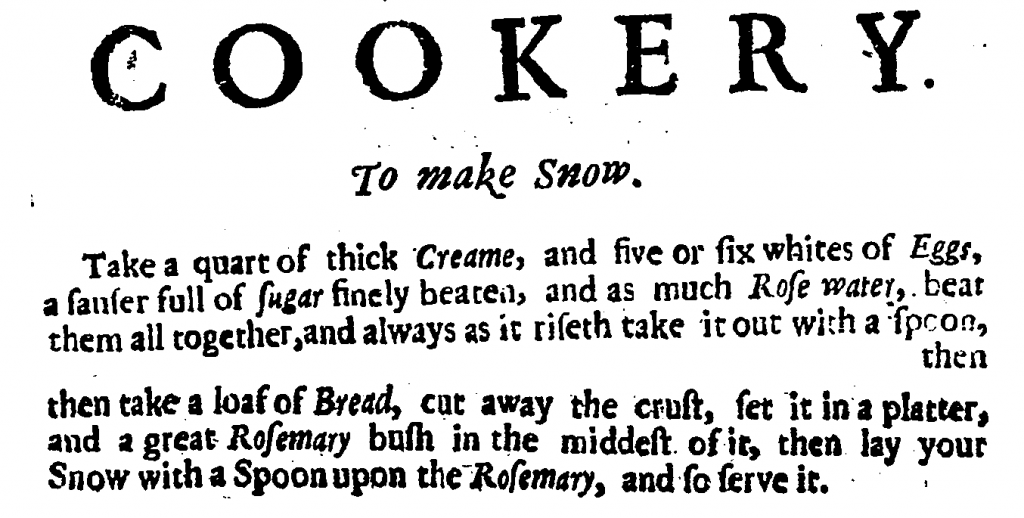

How can you make your White Christmas dreams come true every year if you don’t live in a winter wonderland country like Norway or Canada? Well, you can always try making your own snow. Recipes ‘To Make Snow’ are found in dozens of ‘receipt’ books, both printed and handwritten, in the 16th to 18th centuries. Snow or Snow Cream was a popular dessert, which was made by beating egg whites, cream and sugar until it was light and fluffy.

Different additional flavoursome ingredients could be added to your snow, like almond milk, or musk (from the gland of a deer), or ambergris (from the digestive system of a whale).1 However, thankfully for the deer and the whale, it was far more likely, to find snow flavoured with rosewater.

To show off the snow to its best effect recipes such as this one suggested making a base from a round loaf of bread called a manchet, with all the crusts cut away, or maybe even half an apple [Malus domestica (Suckow) Borkh.].2 Then you could place a branch or ‘bush’ of rosemary in the middle and lay your flurries of snow over and around it.

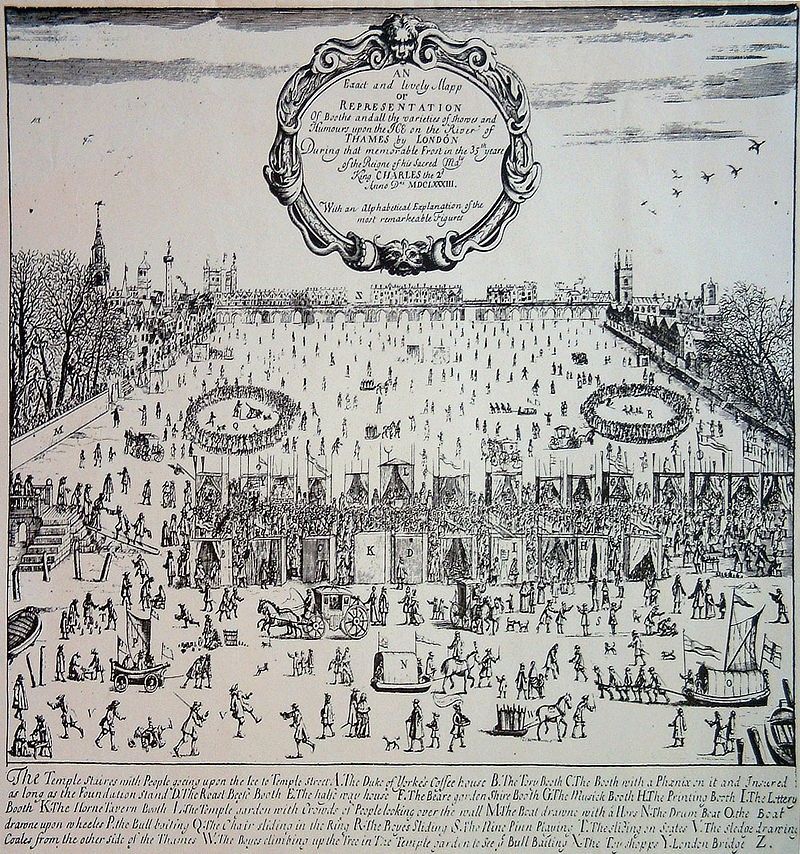

Although this was a relatively simple decoration compared to many elaborate banquet centrepieces, it must have looked pleasingly festive and wintry. Especially as, during this period in the Northern Hemisphere, a weather event which researchers now call the Little Ice Age made many winters extremely cold and snowbound. These cold spells caused the River Thames to freeze over, and the renowned London frost fairs, boasting games, plays, sports, and food stalls were held on the capital’s icy waterway.

Snow-covered trees and fields would, therefore, have been a familiar winter landscape in England. A little tree of rosemary with our frothy, sweet snowy dessert smothering it could have been instantly reminiscent of the festive season.

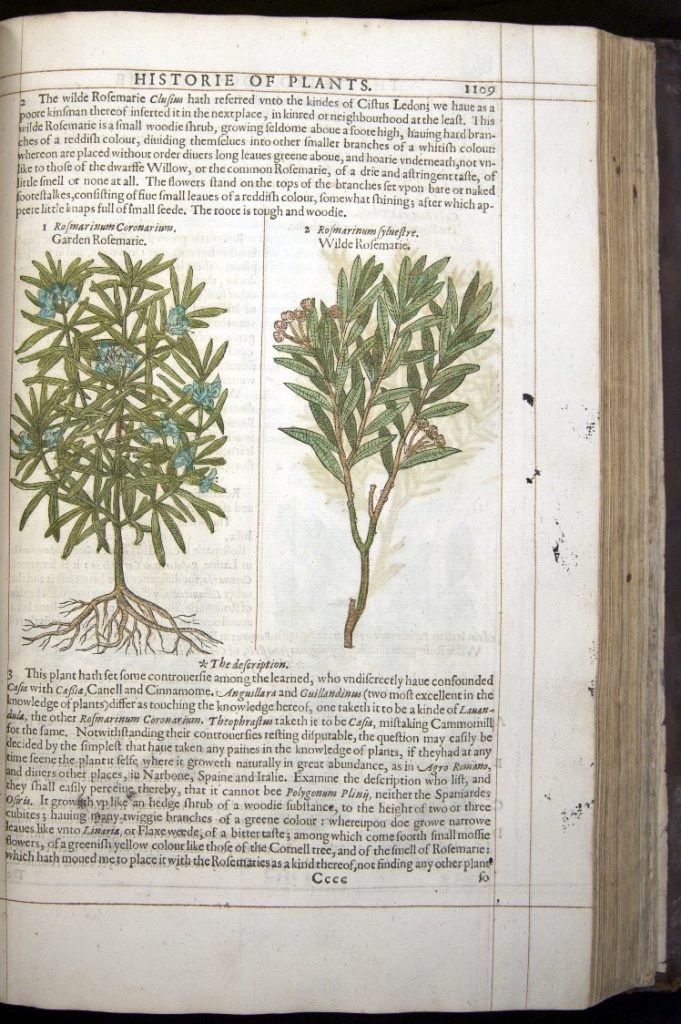

But what of the botanical ingredients in this dish? The early modern recipes for ‘Snow’ combined two very traditional flavours in Elizabethan and Jacobean cooking: rosewater and rosemary [salvia rosmarinus].

Image from the Open University History of Science on Flickr, used under Creative Commons licence (CC BY-SA 2.0)

We know from Shakespeare’s Hamlet that “There’s rosemary, that’s for remembrance”, which was a widespread belief during this period and beyond. John Gerard writes, in his Herball, or General Historie of Plants,3

“The Arabians and other Physitions succeeding, do write, that Rosemary comforteth the brain, the memorie, the inward senses, and restoreth speech upon them that are possessed with the dumbe palsie, especially the conserve made of the floures and sugar, or any other way confected with sugar, being taken every day fasting.”

Rosewater, which was an extremely popular culinary ingredient rosemary was in 16th to 18th century recipes, is the topic of its own Advent Botany blog.

This meant that the addition of rosewater and rosemary in our fluffy, seasonal snow dessert was historically considered not only delicious, but with added health benefits. Let it snow, indeed!

- Receipt Book, ca.1700, Folger, v.b. 272; Anon., Cookery-book: 17th/18th century, 1685-c.1725, Wellcome Library MS1796/45.

- A book of fruit and flowers, 1653 46-47. With an apple: A.W., A book of cookrye Very necessary for all such as delight therin, 1591, 24-5.

- Gerard, J., (1597). Herball, or General Historie of Plants, 1597 edition, page 1111

- Dickens, C., Ainsworth, W.H., and Smith, A., (1841). Bentley’s Miscellany, Volume 9 by ; publisher: Richard Bentley; year: 1841