By James Dinsley

Childhood trips to IKEA

Every year as I was growing up my family would embark on a quest (in what seemed like a Christmas tradition in itself) to visit IKEA, in the hopes of finding the best new and exciting decorations for turning our living room into a Winter wonderland. Whilst it is safe to say that furniture shopping is rarely the highlight of any child’s day, one thing that always stood out to me was the delicious food on offer at the end of the trip: fresh hot dogs, Swedish meatballs and luxury chocolates to name a few. In addition to these meats and confectionaries however, a far less familiar yet iconic drink also caught my attention – lingonberry juice. Whilst the taste was sharp, this ruby-coloured beverage became a favourite of my time at IKEA, and it was rare that I would ever come across lingonberries again in the outside world. I’m sure that my younger self would be bewildered at the prospect that I may one day write an article about these mysterious “lingonberries”, or to find out that they were not as rare or peculiar as he naïvely once believed.

Abisko Expedition

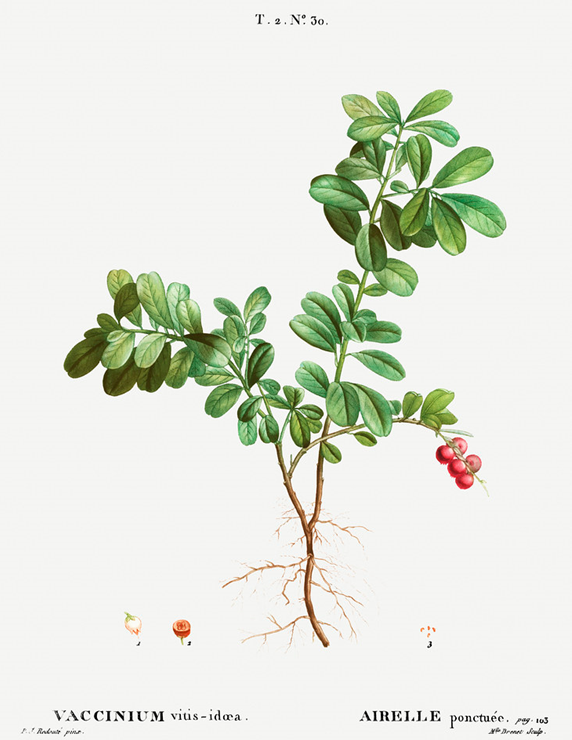

It was when I was 22 years old on an undergraduate expedition to the Abisko National Park in Northern Sweden, situated within the Arctic Circle, that I would discover the true source of this juice in the wild for myself. Vaccinium vitis-idaea (“lingonberry”, or “cowberry”) is a small, evergreen shrub native to colder habitats within the Northern Hemisphere such as Scandinavia, Scotland, Russia, North America and Canada. The Vaccinium genus encompasses over 400 species, including other low-lying evergreen shrubs such as Vaccinium myrtillus (bilberry or European blueberry), Vaccinium uliginosum (bog bilberry) and Vaccinium oxycoccos (bog cranberry). This prostrate shrub forms broad, oval leaves that grow in an alternating pattern and possess a small notch at the tip (Figure 1). These leaves are preserved throughout the Winter, supported by the insulating effect produced by a light blanket of snow cover.

As part of this Arctic expedition, my colleagues and I would study the ecological and climatic controls that influence the biodiversity and dominance of the Vaccinium shrubs at different field sites across the boreal forests, tundra and swamps of the Abisko National Park. To do this, we used one of the most famous, classic tools in a botanist’s arsenal – the mighty quadrat! As flowering and fruiting had yet to occur, identification between the Vaccinium species for a junior botanist was difficult, especially under the repeated attack of the local arctic mosquitoes (Aedes nigripes) and horseflies (Tabantus sp.; Figure 2). However the experience was phenomenal and gave me the opportunity to discover more about the origins of these delicious berries.

The Egtved girl

As a result of the Swedish customary law of Allemansrätten, translating to “everyman’s right” in English, the ability to forage and pick wild berries such as those of the Vaccinium species is permitted. This practice has existed for centuries and is common throughout Scandinavia and Northern Europe. The earliest reporting of lingonberry usage by ancient humans was in the discovery of lingonberry traces in ceremonial beer remnants buried within the grave of the iconic Egtved girl. The Egtved girl was a young woman buried in 1370 BC in present-day Denmark, who lived during the Nordic Bronze Age (1700 – 1100 BC) and was believed to be a merchant traveller, indicating that lingonberries were consumed during this period.

Furthermore, in the 13th century, an Icelandic law was forged to restrict the consumption of lingonberries (and other berry plants) to what could be eaten on the spot, preventing over-consumption and sustaining the population’s food supplies.

Lingonberries come in to cultivation

By the 1600s, lingonberries were grown for decorative purposes by larger, wealthier households under the guidance of respected gardening books such as Le Jardin de Plaisir by the French gardener, André Mollet, in 1651 and Hortikultura written by the Norwegian Christian Gartner, in 1694. This ornamental cultivation practice continued for centuries after, as has been recorded previously with the planting of Vaccinium vitis-idaea fructu albo (white lingonberry) at the Swedish Baldersnäs Herrgård manor house in 1845. Since the 18th century, lingonberries are recorded to have been prevalent in delicacies such as wines, jams and jellies and were accessible to both the richer and poorer members of society. The most destitute members of society at the time had the ability to forage for wild berries via the Allemansrätten, providing a vital and accessible food source to ensure survival even through-out cold winters.

In modern times, global Vaccinium vitis-idaea demand is predominantly met through exports of wild harvested berries from Scandinavia, with some agricultural cultivation and export from the USA. Despite the cultural imprint that lingonberries have had in Northern and Eastern Europe for centuries, the feasibility for the commercial cultivation of lingonberries in Finland, Sweden, Norway, Poland and Russia was only first tested in the 1960s. It is possible that the localised cultivation of Vaccinium vitis-idaea (relative to more widespread, mass-produced fruit such as apples and oranges) is owing to a greater awareness and wider adoption of a close member of the Vaccinium genus, cranberries (Vaccinium oxycoccos, or the North American Vaccinium macrocarpon), by countries such as the UK, USA and Canada

Mustamakkara and other treats

For Christmas, lingonberries are a fantastic accompaniment for many traditional and tasty delicacies. Lingonberry gravy or jam is a common preparation in Scandinavia to partner with meatballs, reindeer, elk and moose steak, alongside a favoured addition for the Finnish specialities of maksalaatikko (liver casserole) and mustamakkara, a porcine blood sausage that is similar to the UK’s black pudding.

As for sweet treats, lingonberries also play a prominent role in another Scandinavian Christmas favourite, Lingonpäron, which uses baked or poached pears preserved in lingonberry juice to produce a sweet and simple dessert. The Norwegian “Trollkrem”, which is a light, creamy mousse whipped up from a combination of egg whites, sugar and lingonberries, also provides a healthy source of sugar for over the holidays. The use of watered lingonberries was particularly valuable many centuries ago, when access to sugar was limited and expensive, as a cheap method of preserving food to last through-out the winter.

Vaccinium vitis-idaea, with its simple leaves and bright red berries, has had culinary, medicinal and ornamental value within the Northern Hemisphere for centuries. Through uncovering the history of this special plant, which once looked so unassuming in my Arctic quadrats, I now discover the origins of the mysterious lingonberry juice that I tried as a child many years ago one Christmas in IKEA.

References

Felding, L. (2015). The Egtved Girl: Travel, Trade & Alliances in the Bronze Age. Adoranten. Pp. 5-20.

Hjalmarsson, I. and Ortiz, R. (2001). Lingonberry Botany and Horticulture. Horticultural Reviews. 27, 79-92.

National Museum of Denmark (n.d.). The Egtved Girl. https://en.natmus.dk/historical-knowledge/denmark/prehistoric-period-until-1050-ad/the-bronze-age/the-egtved-girl/ (accessed 10th December 2020).

Staub, J. (2007). 75 Remarkable Fruits for Your Garden. Utah: Gibbs Smith. Pp. 128-129.

Vänersborgs Museum (2014). Baldersnäs Herrgård Dals Långed. https://digitaltmuseum.org/021015611282/baldersnas-herrgard-dals-langed (accessed 10th December 2020).

For more #AdventBotany see our 2020 index page.