By Natalie Douglas, January 2026

A recent community paper, Parameter Estimation in Land Surface Models: Challenges and Opportunities with Data Assimilation and Machine Learning, addresses a deceptively simple question with far-reaching implications: as researchers, how should we choose the parameters that govern land surface models, and how confident can we be in them?

Land surface models sit at the core of modern climate and environmental prediction. They describe how land exchanges water, energy, and carbon with the atmosphere. This influences everything from daily weather forecasts to long-term climate projections. Many of the parameters that control these models remain uncertain, difficult to observe directly, or variable across space and time. This uncertainty matters: it can strongly influence both model behaviour and the conclusions drawn from simulations.

As decision-makers increasingly rely on Earth system models to inform high-stakes choices — from climate adaptation to carbon budgeting and ecosystem management — it is becoming impossible for researchers to ignore questions about parameter choice and uncertainty. The timing of this work reflects a growing recognition across the community that parameter estimation is no longer a peripheral technical issue, but a central scientific challenge.

Why parameters matter

Parameters are fixed numerical values within a model that represent land surface properties — such as how quickly plants use water or how much carbon soils can store — and they strongly shape how the model behaves. Many modelling systems still treat parameters as fixed values that quietly sit in the background. In reality, they shape how vegetation responds to drought, how soils store water, and how ecosystems take up carbon. Different, equally plausible parameter choices can lead to markedly different model behaviour.

The paper argues that parameter estimation should be viewed not as a one-off calibration step, but as an ongoing scientific process that evolves alongside models, data streams, and scientific understanding. This shift in perspective is increasingly timely, as models grow more complex and observational constraints become richer but also more heterogeneous.

A central role for data assimilation

A core theme of the paper is the role of data assimilation as a unifying framework for parameter estimation. Data assimilation provides a formal way to combine models with observations, allowing each to inform the other in a statistically consistent manner. While these methods are already foundational in numerical weather prediction, their systematic use for land surface parameter estimation is only now beginning to mature.

At a high level, data assimilation offers three critical advantages:

- It provides a transparent and statistically consistent framework for combining models and data.

- It allows uncertainty to be quantified rather than ignored.

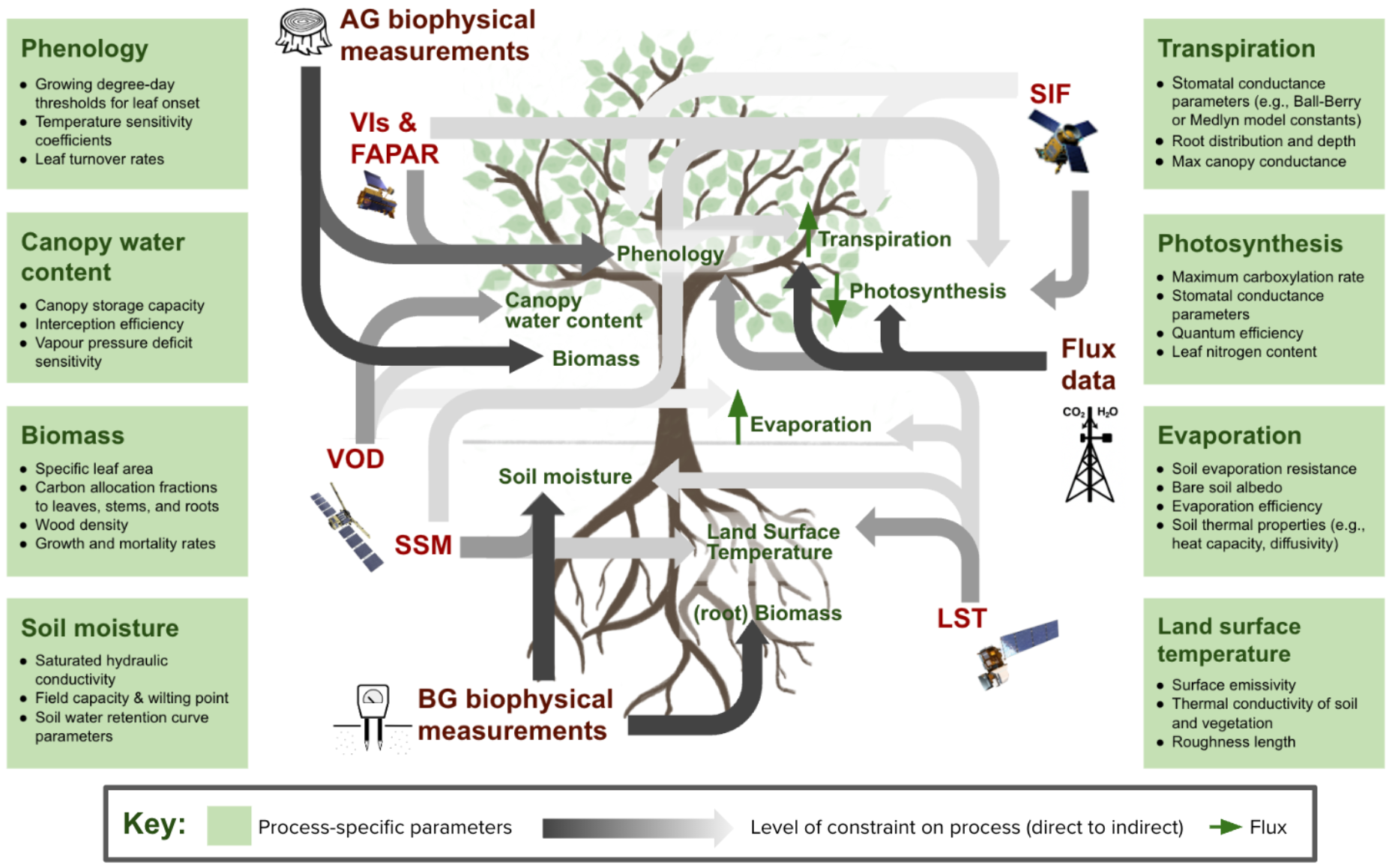

- It enables parameters to be constrained using diverse observations, including satellite products and long-term field measurements – see Figure 1.

Data assimilation does not “force” models to match observations. Instead, it helps to reveal where they perform well and where they struggle. Moreover, it identifies which parameters and processes most strongly control behaviour.

Where machine learning fits in

The paper also addresses the rapidly growing role of machine learning in land and climate science. Instead of positioning machine learning as a replacement for physical models, it presents a more integrated and pragmatic vision. Physical models encode decades of process understanding, while machine learning excels at extracting structure from large, complex datasets.

Used carefully, machine learning can:

- Help identify relationships that are difficult to represent explicitly

- Accelerate computationally expensive components of models

- Support parameter estimation when observations are sparse, noisy, or indirect

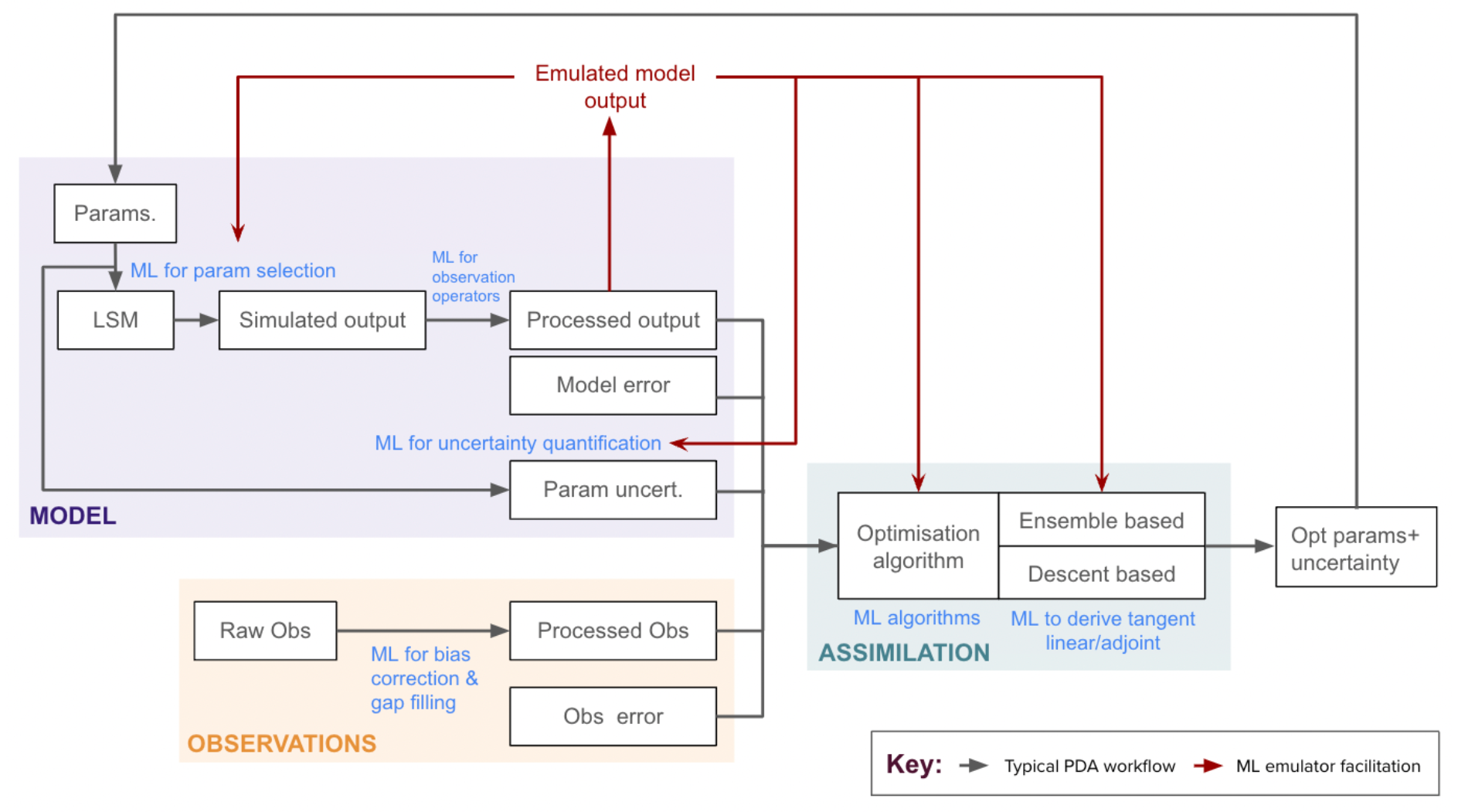

The most promising direction is the development of hybrid approaches. These can combine physical modelling, data assimilation, and machine learning in ways that are both flexible and physically interpretable – see Figure 2.

A timely contribution with early momentum

The response to the paper suggests that it has arrived at a particularly opportune moment. It has already been taken up and cited by studies exploring new approaches to parameter estimation, uncertainty quantification, and hybrid modelling frameworks. This early uptake reflects a broader appetite across the community for more systematic, transparent, and data-driven ways of confronting long-standing uncertainties in land surface modelling.

Rather than simply summarising the state of the art, the paper is increasingly being used as a reference point for framing new work in this rapidly evolving area.

A genuinely cross-disciplinary effort

The paper brings together perspectives from land-surface modelling, data assimilation, and machine learning. That breadth is not incidental: the challenges it addresses sit at the intersection of theory, computation, and observation. No single methodological tradition can solve them.

This cross-disciplinary perspective is essential if the next generation of land-surface models is to be both more realistic and more honest about uncertainty.

Looking ahead

At its core, the paper is both a synthesis and a forward-looking statement. It argues for a shift in how the community thinks about parameters, uncertainty, and the relationship between models and data. In particular, it encourages researchers to:

- Treat parameter estimation as a core scientific problem, not a technical afterthought

- Embrace uncertainty as something to be quantified, understood, and communicated

- Develop hybrid approaches that combine physical insight with data-driven methods

Environmental models continue to play an ever larger role in informing decisions about climate, ecosystems, and resources. This makes improving the estimation and evaluation of their parameters increasingly critical. The work highlighted in this article contributes to that broader shift. With it, we can outline a more rigorous, transparent, and data-rich future for land-surface modelling.