By Zakiyah A. Alsiddiqi (PhD Student – School of Psychology and Clinical Language Sciences)

Research has shown that early years’ experiences in children’s lives lay the foundation of their later learning success. Early behaviours and interactions in their environments nourish their communication and learning skills. Reading is the window for learning; therefore, it is important to know when children begin learning to read.

As we know, formal reading instruction begins once the child reaches school age. However, in reality, pre-literacy skills for reading emerge when children are much younger (i.e., in preschool or even younger). Crucial pre-literacy foundation skills include oral language (i.e., listening & speaking), phonological awareness (i.e., the ability to attend to and work with sounds in spoken language), letter knowledge, and understanding common print concepts (e.g., whether print goes from left to right, and top to bottom of the page). So, how can we foster children’s pre-literacy skills?

Although learning letters is essential for reading in an alphabetic script like English, oral language skills are the foundation for literacy development. Research has shown that different language skills are intertwined with literacy skills. Also, many studies have suggested that language difficulties may hinder the development of literacy. It is therefore important to enhance children’s oral language skills, and parents and teachers play an active role by providing rich language experiences. Oral language skills can be fostered by: (1) providing authentic conversations between children and adults, (2) asking open-ended questions and encouraging children to do the same, (3) exposing children to diverse vocabulary, (4) facilitating active listening and the expression of thoughts and ideas, and (6) using stories to foster language comprehension and use.

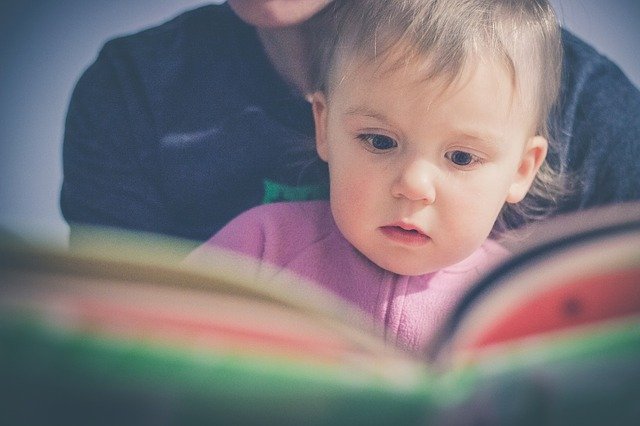

Shared book activity is one of the best ways of enhancing children’s language skills. It incorporates both language and literacy at the same time. Through book reading, new words, grammar rules, concepts, and feelings are introduced to children. Also, by reading to children, parents expose them to print and letters and may indirectly increase children’s motivation and interest in reading. Book reading activity acts as a link between oral and written language skills, and it promotes letter knowledge and print concepts skills. Developing the concept of print is a key pre-literacy skill. It includes knowing how to hold a book, turning pages, the direction of reading (i.e., left to right, or right to left, and top to bottom), learning to identify the units of the writing system, i.e. letters in alphabetic systems like the one English uses, differentiating between letters and words, and understanding that a written script conveys meaning. Parents also may promote their children’s letter knowledge skills by encouraging them to look at different letter shapes, learning their name, and linking letters to their corresponding sounds. Phonological awareness is another important pre-literacy skills. It is the ability to hear and manipulate sound structures within spoken words. Parents may play with sounds to foster their children’s phonological awareness. During shared book reading, parents may draw their children’s attention to rhyming words, encourage them to sound out the words, blend the sounds to say a word, clap out each word of a sentence (e.g., I-will-eat-an-apple) or segment the a word into syllables (e.g., rain-bow), or even isolate the first sounds of the words (cat begins with c).

While it is important to understand pre-literacy skills, it is equally important to know that not all children acquire these skills at the same pace. Some children may struggle and this might be indicative of broader difficulties with language leading to later literacy difficulties. Some children who have difficulties with learning to read and write also have underlying language and communication difficulties in the absence of a known biomedical condition (e.g., autism, cerebral palsy, hearing loss, etc.). For these children difficulties with language tend to be persistent, may affect both understanding and language use and can have lifelong consequences for their social and emotional wellbeing, for their behaviour, and for their academic success. Children with this profile are typically diagnosed by a speech and language therapist as having a Developmental Language Disorder – DLD (see the RADLD website for more information on DLD). Children with DLD are 6 times more likely to have reading difficulties than their peers (McGregor, 2020) and it is imperative to raise awareness so that professionals and parents can provide the appropriate support.

Understanding how language and pre-literacy skills are related allows professionals to tailor their intervention to the child’s needs. For example, speech and language therapists (SLTs) would administer a comprehensive language assessment to identify areas of need and provide an individualized therapy plan. Further, they would address pre-literacy skills in their assessment and intervention as well. Parents of children with DLD could help their children by exposing them to books, reading to them regularly, and incorporating different speech and pre-literacy activities during reading time.

As part of my Ph.D. project, I am exploring the relationship between oral language and pre-literacy skills in Arabic-speaking children with and without DLD. Given the differences between English and Arabic, I am investigating which linguistic skills might be most related to pre-literacy skills in Arabic. Is it the same as in English or different? Based on the existing literature, I predicted that children with DLD would perform lower on all emergent literacy tests than their typically developing peers. I also expected that oral language skills would be related to emergent literacy skills in both groups.

To test these hypotheses I recruited a group of 24 children with DLD and 40 typically developing peers aged between 4 and 6. I tested children’s knowledge of words, grammar and their language understanding, alongside their emergent literacy skills: phonological awareness, letter knowledge, and decoding. The study’s findings are consistent with research on English-speaking children. Children with DLD performed lower than typically developing peers in all emergent literacy tasks. The preliminary findings also show some evidence of a relationship between oral language and emergent literacy skills in both groups. In-depth analyses are still in progress to investigate language predictors of emergent literacy in Arabic. Findings from this project will provide a preliminary description of the pre-literacy skills in Arabic speaking children with and without DLD, and a better understanding of the relationship between language and emergent literacy in Arabic language. This is the kind of research evidence that SLTs and education professionals need to assist Arabic-speaking children who are currently struggling with language and literacy.

The study is funded by King Saud University in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia and supervised by Prof. Vesna Stojonavik and Dr. Emma Pagnamenta (University of Reading, UK).