By Meg Cathcart-James

Back in 2017, I wrote an Advent Botany article about juniper; its links to Christmas and myriad culinary uses, including its role as the main botanical in gin. I thought it was high time we delved into the source of gin’s quintessential partner – tonic water! Fantastic as this delicious mixer is, the plant that flavours it is most famous for an entirely different reason.

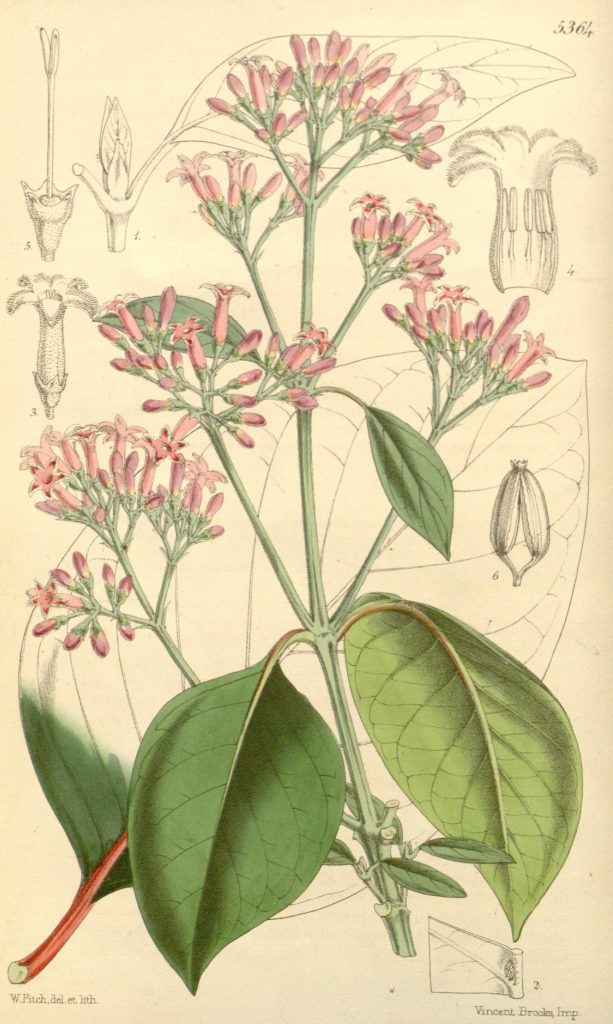

Cinchona officinalis is an evergreen shrub or small tree of the family Rubiaceae, native to mountainous regions of South America and is the species usually associated with quinine however this species has low quinine yields and commercial species are usually C. calisaya and C. pubescens (Andersson, 1998; Predergast & Dolle 2001). I think it’s fair to say that the cinchona tree is a plant that has saved lives for centuries.

Fever tree or Jesuit’s bark

Known as the ‘fever tree’ (remind you of a certain tonic water brand?), the bark has been used by natives as a medicine since time immemorial; Spanish missionaries brought it to Europe (hence the name Jesuits bark). In addition to alleviating fever, relaxing muscle spasms or cramps and relieving pain, it was also used in the treatment of the deadly disease malaria. The chemical compound responsible for the bark’s medicinal capabilities, quinine, was isolated by French researchers in the early 1800’s. They named it after the native Quechua word for the tree – ‘quina-quina’, meaning ‘holy bark’. Purified quinine became the standard treatment for malaria and remains an important drug in its treatment to this day.

Fever-tree describe their discovery of an old plantation of Cinchona ledgeriana in the Democratic Republic of Congo as the base for their Premium Indian Tonic. C. ledgeriana is now included in a broader concumscription of C. calisaya. I feel I should add that other mixers are also available… Schhh, you know who, voiced famously for eight years by William Franklyn. Cinchona tree bark has always been considered very bitter, and people have prepared it in various ways to make it more palatable. In true British style, colonialists in India who had to take a quinine tonic to prevent malaria loaded it with alcohol – gin, of course – to help the medicine go down! And so, the classic gin and tonic we Brits cherish was born.

Whilst the cinchona tree doesn’t immediately shout ‘Christmas’ to the masses, for me gin and tonic is my family’s quintessential festive drink; one of those little family quirks! Perhaps this year more than ever, those traditions and flavours we hold affection for, and find comfort in, should be embraced. This Christmas, hopefully with my gin-quaffing family around me, I will find my festive comfort in the essence of the fever tree.

References

Andersson, L., 1998. A revision of the genus Cinchona (Rubiaceae-Cinchoneae). Memoirs-New York botanical garden.

Maldonado, C., Barnes, C.J., Cornett, C., Holmfred, E., Hansen, S.H., Persson, C., Antonelli, A. and Rønsted, N., 2017. Phylogeny predicts the quantity of antimalarial alkaloids within the iconic yellow Cinchona bark (Rubiaceae: Cinchona calisaya). Frontiers in Plant Science, 8, 00391.

Prendergast, H.D.V. & Dolle, D. (2001). Jesuits’ Bark (Cinchona [Rubiaceae]) and Other Medicines. Economic Botany, 55(1) 3-6

Editor’s note

For me, one of the fun things about tonic is the intense fluorescence of quinine under UV light!

For more #AdventBotany see our 2020 index page.