By Claudia Ciotir

Date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.), is a socio-economically important tree due to its food, fibre and construction material uses in arid and semiarid regions of the world. It is a monocotyledonous dioecious tree producing male and female flowers on separate individual plants. Morphologically, male inflorescences are protected by an inflated spathe with flowers developing visible petals and anthers, while female flowers lacking petals are protected by a flat spathe with globular ovaries (Figure 1).

Origin of date palms

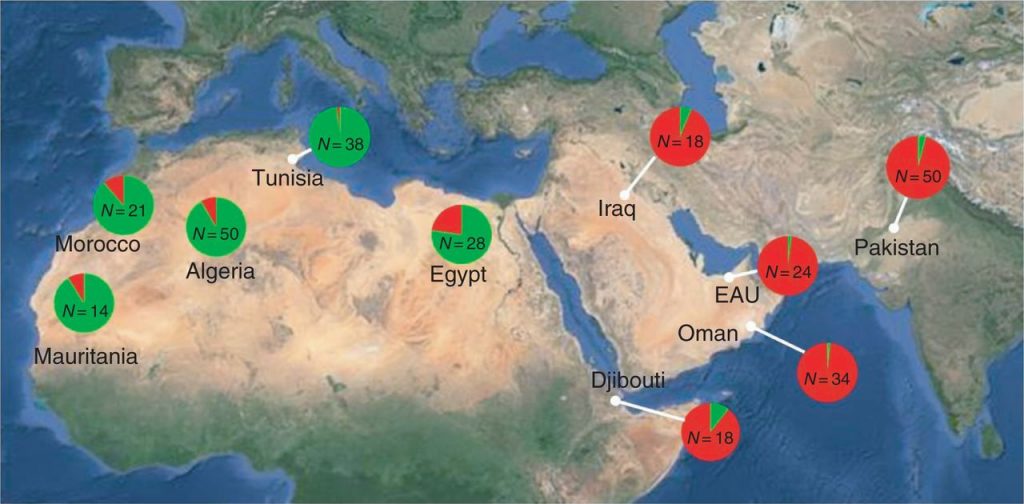

The origin of date palm remains obscure (Mohamoud et al. 2019) and molecular evidence suggests multiple domestication events. Morphometric analysis of seed shape (Gros-Balthazard et al. 2016, 2017; Terral et al. 2012) indicates an origin in the Middle East around the Persian Gulf with some of the most distinct populations in the mountains of Oman. The Persian Gulf region near Abu Dhabi has ancient Neolithic sites with preserved charred seeds calibrated to the late sixth and early fifth millennia BCE (Beech and Shepherd 2001). Recently Zehdi-Azouzi et al. (2015) have sugested multiple origins of domesticated dates due to the very distinctive patterns of genotype found in north Africa in contrast with those typical of the Middle East.

Traditionally, date palm was cultivated in the Middle East and North Africa, later introduced to favourable climates in California, Peru and Australia and in many areas with hot and dry climates (Tengberg 2014). Although dates are essential food and an important commercial crop in Middle Eastern countries, they are currently consumed as winter dry fruit in most countries of the world.

Long lived seeds

The longevity of date palm seeds is outstanding. In Israel, the Judean date palm (extinct from cultivation) has been revived from 1900years old seeds recovered from the historical site of Masada in vicinity of the Dead Sea (Sallon et al. 2008). In Haifa city, as in many areas of warm temperate climate, date palms are planted in public streets and gardens.

Identification of gender

Each female inflorescence yields half male and half female seeded fruits. Most date plantations plant female trees and only few male trees for pollinations. For a manual and automatic pollination foresights enjoy the amazing video of Dates Palm Cultivation Process from planting until harvesting and packaging (courtesy of Agriculture Technology Inc.).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4QeRF3m5IlM

Until recently, male and female plants could only be identified in mature trees at the flowering time. Date palms usually reach maturity between 4-8 years of life, but the Thai cultivar cv. KL1 matures within two years (Intha and Chaiprasart 2018). However, growing trees with unknown sex is uneconomical for date plantations especially in arid areas where fertile land and water resources are scarce. Although multiple studies released methods to identify dates tree sex, a simple molecular method to differentiate sex chromosomes in early stage of seedling was developed in Thailand by Intha and Chaiprasart (2018).

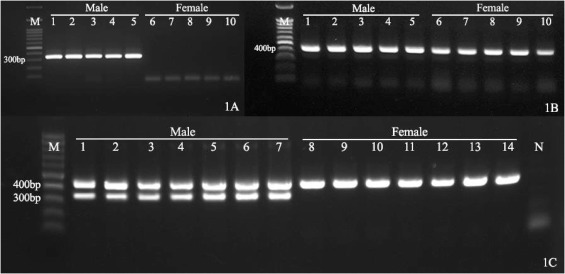

Phoenix dactylifera is a diploid species with 2n=36 chromosomes. Male sex chromosomes are heterogametic (XY) and female are homogametic XX. To facilitate sex identification Intha and Chaiprasart (2018) developed PCR markers specific to sex chromosomes amplifying PCR bands of different lengths in seedlings. For example, a 430 bp is amplified from chromosome X and a 320 bp from the Y chromosome. As a result, male genotypes amplify two PCR fragments of different lengths while female genotypes amplify only the 430bp long (Figure 2).

Figure 2. PCR profiles of sex determination in date palm consists of a combination of primers used to amplify fragments of 320bp specific to the male Y chromosome and 430bp specific in the X chromosome of both male and female genotypes (Intha and Chaiprasart 2018).

References

Beech M. and Shepherd E. 2001. Archeobotanical evidence for early date consumption on Dalma Island, United Arab Emirates. Antiquity, 75:83-89. http://www.adias-uae.com/publications/dates.pdf.

Gros-Balthazard, M., Newton, C., Ivorra, S., Pierre, M.H., Pintaud, J.C. and Terral, J.F., 2016. The domestication syndrome in Phoenix dactylifera seeds: Toward the identification of wild date palm populations. PloS one, 11(3), p.e0152394. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0152394

Inthaab N. and Chaiprasartab P. 2018. Sex determination in date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) by PCR based marker analysis. Scientia Horticulturae, 236: 251-255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2018.03.039.

Gros-Balthazard, M., Galimberti, M., Kousathanas, A., Newton, C., Ivorra, S., Paradis, L., Vigouroux, Y., Carter, R., Tengberg, M., Battesti, V. and Santoni, S., 2017. The discovery of wild date palms in Oman reveals a complex domestication history involving centers in the Middle East and Africa. Current Biology, 27(14), pp.2211-2218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2017.06.045

Intha, N. and Chaiprasart, P., 2018. Sex determination in date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) by PCR based marker analysis. Scientia Horticulturae, 236, pp.251-255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2018.03.039

Mohamoud, Y.A., Mathew, L.S., Torres, M.F., Younuskunju, S., Krueger, R., Suhre, K. and Malek, J.A., 2019. Novel subpopulations in date palm (Phoenix dactylifera) identified by population-wide organellar genome sequencing. BMC genomics, 20(1), 498. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-019-5834-7

Sallon, S., Solowey E., Cohen Y., Korchinsky R., Egli M., Woodhatch I., Simchoni O., Kislev M. 2008. Germination, genetics and growth of an ancient date seed. Science 320(5882):1464 (2008). DOI: 10.1126/science.1153600

Tengberg M. 2014. Date Palm: Origins and Development. Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-0465-2_2175.

Terral, J.‐F., Newton, C., Ivorra, S., Gros‐Balthazard, M., de Morais, C.T., Picq, S., Tengberg, M. and Pintaud, J.‐C. (2012), Insights into the historical biogeography of the date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) using geometric morphometry of modern and ancient seeds. Journal of Biogeography, 39: 929-941. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02649.x

Zehdi-Azouzi, S., Cherif, E., Moussouni, S., Gros-Balthazard, M., Abbas Naqvi, S., Ludeña, B., Castillo, K., Chabrillange, N., Bouguedoura, N., Bennaceur, M. and Si-Dehbi, F., 2015. Genetic structure of the date palm (Phoenix dactylifera) in the Old World reveals a strong differentiation between eastern and western populations. Annals of Botany, 116 (1), pp.101-112. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcv068

For more on dates you can read our previous #AdventBotany blog here.