By Ieuan Higgs, February 2026

Perception of AI

Artificial intelligence (AI) has become closely associated, in the public imagination, with large language models (LLMs). From a user perspective, AI chatbots such as ChatGPT or Claude operate on a simple and intuitive principle: text goes in and text comes out (or some combination of text, images, sound, and/or video). This framing has made AI feel familiar to millions. However, it has also narrowed the way in which we might sometimes think about AI, the forms which AI can take, and the potential for beneficial scientific AI applications.

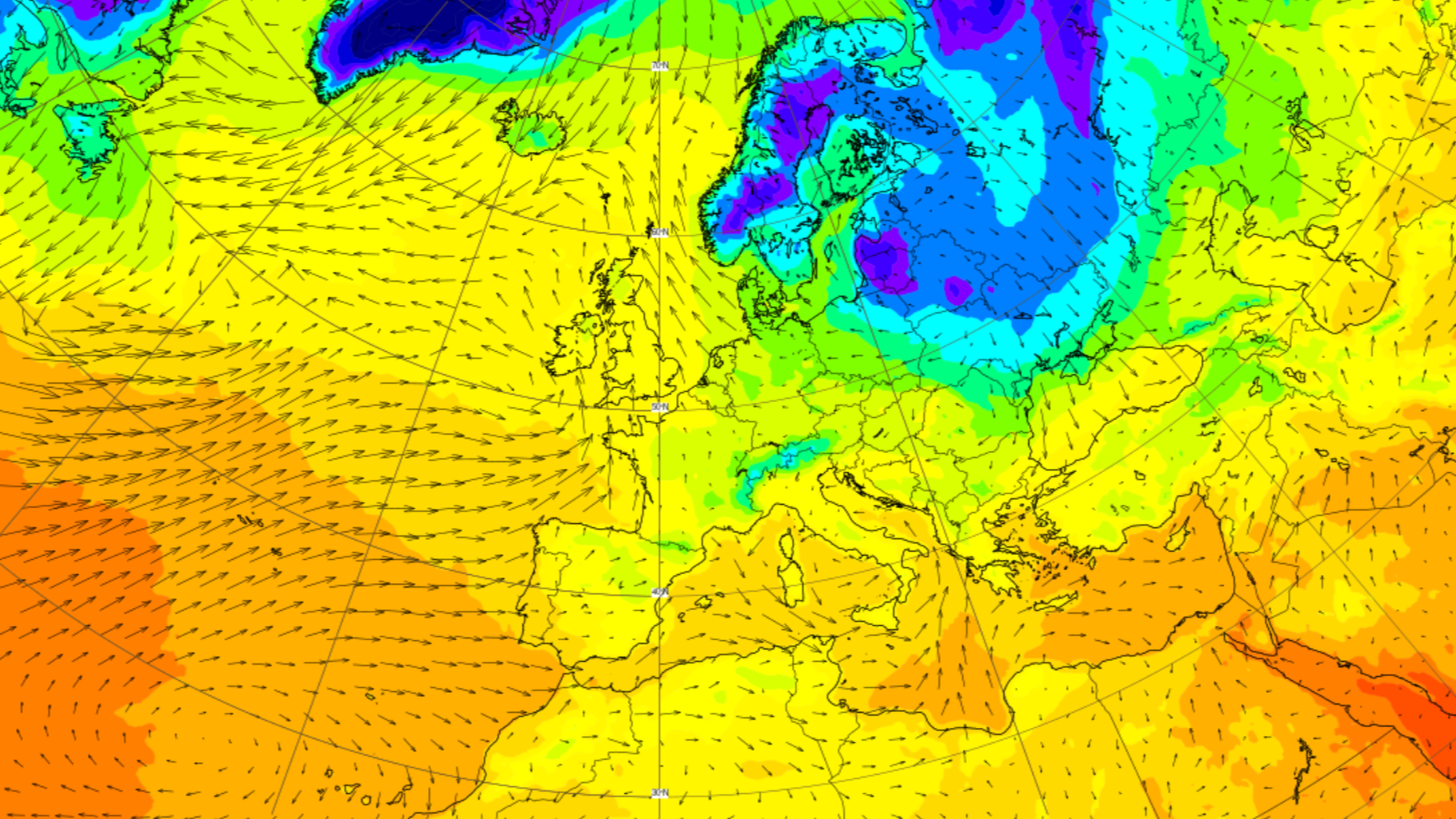

Weather prediction and Earth system scientists are developing AI in ways that look very different from conversational chatbots (even if they use many of the same underlying components and optimisation methods). Rather than generating text or media, these models operate on large amounts of numerical data. Their purpose is to attempt to predict the future evolution of Earth system processes. These AI applications can directly benefit people by informing hazards and emergency responses, including storm warnings, flood risk, and heatwave risk. This contrasts quite heavily with some well-known AI applications, which have confusing-at-best and deliberate-misinformation-at-worst impacts on society (is a cat video on social media even funny if it isn’t real?).

Earth system AI models can already offer gains in some operational settings. This is because AI generated forecasts are faster to compute than traditional physics-based model forecasts (while maintaining comparable accuracy). However, if we are using these models in safety critical settings, how do we know we can trust the output?

Trusting AI in Earth Science

The main factors affecting trust in AI models usually reflect the differing development paradigms of AI and physics-based models.

At a basic level, the two types of model can look very similar. AI weather models (e.g., AIFS or FourCastNet) often take inputs and produce outputs in the same format as physics-based models. These inputs and outputs are gridded fields of atmospheric variables, including temperature, wind, and pressure. The model evolves the gridded input fields forward in time to produce output fields. These grids contain spatial, temporal, and multivariate structure which corresponds to physical processes such as weather fronts, atmospheric waves, and cyclones.

However, in traditional physics-based models, this structure arises from model equations which explicitly encode physical laws. Conservation laws, thermodynamics, and fluid dynamics constrain how information propagates through the system. The complex behaviour of the atmosphere can emerge from these first principles. Decades of development and validation have built confidence in how these models behave. Importantly, this includes an understanding of their limitations.

Beyond the AI models being new and lacking this time-in-operation, they also approach the problem from a fundamentally different direction. They do not encode physical laws directly. Instead, the AI models train on examples of atmospheric evolution (e.g., a historical record of combined model runs and real observations). They must then infer internal representations that allow them to make predictions on unseen examples (i.e., data which the model is not trained on). If successful, the model has captured something meaningful about atmospheric dynamics. However, this immediately raises some critical questions:

- How do we know that the internal logic the model has learned is physically sensible and aligns with domain knowledge? Is it merely statistically convenient?

- Is the internal logic fully representative, such that the model will generalise well to unseen cases? Or has it learned spurious relationships and shortcuts?

Explainable AI

Now, the questions posed above begin to point us at the field of explainable AI (XAI) for answers. Can we check if a model does the right thing for the right reasons?

Explainable AI provides a collection of methods designed to interrogate models beyond the validation of outputs. These techniques aim to probe the internal mechanisms of a neural network, helping us understand how the network transforms inputs into outputs and makes particular predictions. In this sense, XAI tools represent a new class of diagnostics. Some of these are analogous to the diagnostics routinely applied to physical models.

So, why are you talking about this on a data assimilation blog?

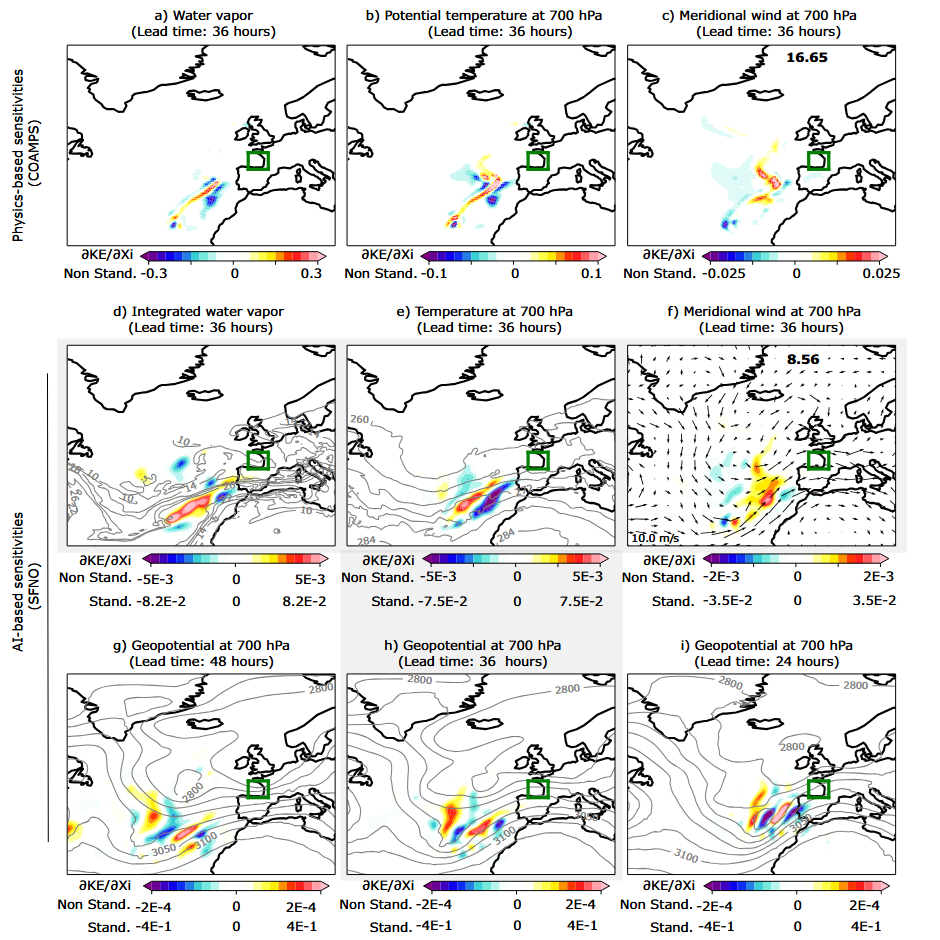

Out of the many parallels between AI and data assimilation (DA), explainability is where a particularly natural connection emerges. A widely used XAI technique is saliency analysis, often implemented using vanilla gradients. This gradient-based approach uses backpropagation to compute the sensitivity of a chosen output with respect to each input. This can highlight which parts of the input most strongly influence a given aspect of a neural networks output prediction.

This perspective is closely related to adjoint-based sensitivity methods developed in the context of variational DA. In variational DA, adjoint models are used to compute gradients of a cost function. This typically combines model dynamics with observations to estimate optimal initial conditions. The same adjoint machinery can also be used outside the assimilation problem to quantify how perturbations to inputs propagate through a dynamical system and affect a chosen output. From this perspective, saliency-related analysis may be viewed as an adjoint-style sensitivity calculation applied to neural networks rather than physical models.

Seen in this light, the connection above shows just one way in which ideas from DA and AI can be combined through XAI. Concepts for sensitivity analysis naturally align between two distinct-but-related fields. Both use gradient information to assess how inputs influence outcomes. This shared perspective provides a natural foundation for transferring established adjoint-based sensitivity concepts to the interpretation, evaluation and trust-building of AI-based forecasting systems.