Samuel Beckett Research Centre Visiting Research Fellowship programme 2026

-

Priority will be given to candidates and applications that show the greatest academic promise and whose current and proposed research demonstrates a good fit with UoR holdings

-

If a PhD student, applicants must be close to submitting their thesis at the time of application to this call (please include expected submission date) and be able to take the Fellowship up this academic year

-

Applicants must be eligible to apply for either UK postdoctoral schemes such as the British Academy Postdoctoral Fellowship scheme and the Leverhulme Trust Early Career Fellowship (or equivalent) when they complete their Visiting Fellowship, and/or EC Marie Curie Postdoctoral Fellowships; candidates in existing academic posts must be eligible to apply to external grant awarding bodies (national or international) in collaboration with the SBRC.

-

Project details to include: title of project, proposed start and end date of fellowship, objectives, methodology, an outline of potential sources to be consulted, and a description of how this project will build upon your existing research (500 words max)

-

Funder/funding scheme you are intending to apply for (250 words max)

-

An up-to-date curriculum vitae (maximum 2 pages), including publications list

-

An allowance up to a maximum of £2,000 to cover travel, accommodation and living expenses during the Fellowship (subject to UK tax and National Insurance)

-

Support from SBRC academic staff, expert curators, and UoR Research Development Manager

-

Workspace and reading room provision

-

You will write up a blog post or contribute to a podcast episode at the end of the project and contribute to the wider SBRC research culture

-

Visiting Fellows must spend time in the Beckett Collections at the University of Reading developing their project

-

All awarded funding must be spent before 10 July 2026

-

Fellows will work with SBRC academics and the Research Development Manager to develop concrete plans for research funding applications or other grant/collaborative bids, to be submitted at an agreed time.

Being Poorly with Samuel Beckett (An Addendum)

Amy Grandvoinet

Royal Berkshire Hospital’s A&E department is directly opposite the Museum of English Rural Life, where the Samuel Beckett Special Collection at the University of Reading is held, and which I’m calling the Beckett Centre. In that A&E, as in most A&Es, there is a waiting-room. Some people are more comfortable in the waiting-room than others; some are not comfortable at all. In 2023, we went to a Wellcome-Trust-run ‘Waiting Times’ conference on Euston Road, co-hosted by Dr Laura Salisbury who scholars on Beckett and health occasionally. The conference took place near Tavistock Square and Tavistock Place and Tavistock Square Gardens, nomenclaturally reminiscent of the Tavistock Centre (NW3 5BA) where Beckett received psychotherapy in the early-to-mid 1930s.

We were invited to the conference by somebody I’d been to secondary school with in the post-war New Town of Bracknell (coincidentally close to the Beckett Centre). After attending the conference, which discussed Beckett a lot, I experienced medicality-related flashbacks from that secondary-school-in-Bracknell era at what should have been a delightful park-café we’d found. I tried to write them down and got confusingly – for myself and my company – upset. Not long ago, GIG Cymru or NHS Wales gave me a P.T.S.D. diagnosis, a condition affecting at least 1-in-10 humans in the UK & Ireland today.

It was so nice to be able to go to the Beckett Centre and continue to work out, while investigating the (non)presence of ‘psychogeography’ in Beckett’s gestalt, such persistent mind-hums. An unexpectedly busy episode prior to arriving, however, had turned them up Mezzo piano to Forte. I got to the Beckett Centre whacked and relapse-y. The Sure Hotel by Best Western Reading where I’d be staying assigned me a room that felt scary and I got all upset. Reading is full of personal memories, and I was anticipating pleasant-yet-intense reunions ahead, as well as the pressure of research success. Things felt awry. Enter heart palpitations, brain-fog / delirium, night-sweats and night-mares, large headache. I developed a mouth ulcer.

James Knowlson’s authorised biography tells you Beckett suffered depression and acute anxiety in his late twenties – an arrhythmic heart, night-sweats, night-mares, shudders, panic, breathlessness, paralysis. Symptoms augmented in 1933 after he translated André Breton’s and Louis Aragon’s ‘The Fiftieth Anniversary of Hysteria’, concurrent also with the death of his Daidí. Beckett began psychotherapy in London where he’d joined Thomas MacGreevy from Dublin. Between walking or reading or sipping on lime-juice, says Knowlson, Beckett saw Dr Wilfred Bion almost one-hundred-and-fifty times over a period of two years (though this felt to him only six months). Beckett lay on couches, Beckett dream-diaried, Beckett educated himself via Robert S. Woodworth’s Contemporary Schools of Psychology (1932). He believed the ventures somewhat alleviated his debilitating disturbances.

Beckett is known for being tenacious. He survived a near-fatal stabbing in 1938, recovering from a coma in Hôpital Broussais. He fought in the French Resistance in the mid-1940s, before beginning his frenzy-of-writing epoch in Paris. In the late 60s, Beckett was treated at Hôpital Cochin for a bad lung-abscess involving a technique of hypnotic rêves éveillés dirigés (guided waking dreams in which he remembered walks with his father) and forwent the pleasures of alcohol and cigarettes, confined to his flat at 38 Boulevard Raspail until he was better. Beckett never ceased writing, but this too seems bound up in sickness-talk: he wrote to a friend in 1954 ‘I am absurdly and stupidly the creature of my books’. Which are often about affliction and dying.

To what extent did writing deleteriously effect Beckett’s psyche? Frenzy. When at the Beckett Centre, I admit to Steven Matthews (the centre’s director) just how many notes I’ve made, way too exhaustingly Joyce-ish and not enough pared-back Beckett but am reassured (?) that Beckett made loads loads and loads of notes also. I say I’m ofnadwy (poorly) and Steven says he’s wedi blino (tired). Someone else and I spoke at the Beckett Centre on the potential obsessiveness occurring with writing projects, ousting valorisations of harmful ‘creative’ habits. I remember the importance of NOT PROJECT, as well as of project. Projects can give life, but also derail it? All in good measure? Tá?

I went to A&E at the Royal Berkshire Hospital when the headache had reached its seventh-day and was now freaking me out. In A&E, everyone chatted about how long they’d been there. ‘I’ve been waiting here for ages,’ said a lady. ‘Gosh, how much longer?’ said a man, looking at his wrist-watch. Once, I watched Waiting for Godot (1954) on my Fairphone 2 in the bath at the sanctum ‘The House of Virtue’ (where I lived with two angels proto-healing ravenously) and missed the ending as water gurgled loudly down the plughole, which seemed very fitting it is a story I like to repeat at parties. A&E’s ceilings were static trompe-l’oeil sky-lights, which people rustled biscuit-packets under from the free tea cart. Eventually leaving with codeine, steroids, and conflicting dose instructions, I ripped off my QR-coded NHS wristband and gained a hot new bookmark.

At the Beckett Centre I read someone say only great writers are unafraid of shame and thus capable of creating literature carrying within it humanity’s imprint. Nervously, I consumed my new meds (plus a.t.m.-usual Sertraline) at breakfast in the Sure Hotel by Best Western Reading. I tried to visualise Beckett in spates of recuperation, seeking figmentary solidarity. Manuscripts in the Beckett Centre listed instances in Waiting for Godot when its four players ask each others’ assistance below a subtitle HELP. As well as his tenacity, Beckett is known for his kindness. To cross things out, he typed ‘x’s over glyphs on type-written documents, reminding me of a while ago crossing out hand-written errors with love-hearts as acts of self-care. My G.P. recently recommended reading Montaigne (+ EMDR) as opposed to more talking therapies; I lol when witnessing Francophilic t-shirts in Reading town-centre emblazoned PARIS AVENUE MONTAIGNE 75008 PARIS and MON AMIE PARISIENNE. I bought neither of them. We had drinks by the Seine wait no the Kennett that flows beneath the Oracle Shopping Galleria.

Unsatisfied with the NHS (where you must pay for prescriptions unlike yr GIG), I went to MyDentist and found I need not worry about suspected temporal arthritis or other mystery ailments, but take anti-biotics to solve a trauma-ulcer caused by a wisdom tooth. MyDentist is one-hour away from the Beckett Centre, a liberating stroll on Bath Road and past Prospect Park to a neglected precinct in Tilehurst. Beckett, did you know, had lots of teeth out. She told you they(’d) consider(ed) you an enigma, and we talked of Point Royale.

The next day at a new arts venue named Reading Biscuit Factory I attempted drinking a small glass of vin rouge watching The Substance (2024), which features a disgusting crustacean scene (Beckett did not like to see lobsters in fish-tanks at restaurants fyi) and the slicing of human skin. Nauseously, I got up to leave and collapsed, crawling out of Screen 3 and into the foyer where duty-of-care staff phoned 999. Did Beckett undergo immersive ciné too? Phone-call paramedics asked if my head felt like it had been hit with a brick and whether I looked deathly pale, among other alarming questions surely designed to arouse lucidity. Meanwhile, four dolphins leapt in Paradise Aberystwyth.

I could not bring myself to go back to A&E as a courtesy 111 check-up call later advised, and I don’t think Beckett would have wanted to either. Instead, I read through my notes from the Beckett Centre so-far back at the Sure Hotel by Best Western Reading, and slept relatively soundly. Another guest, I’d overheard, believed ‘The rooms are not nice’ here, but personally I’d grown fond of the Sure Hotel by Best Western Reading, where Beckett’s books were all laid out all over my bed. Many ambulances sirened in the night outside. We are legitimately concerned about health, but health-scare can really take over! Sometimes I dreamt about Beckett doing normal things, like brushing his teeth or opening cupboards, which was bon.

Matin, a sister sent a sympathetic WhatsApp message: ‘It’s been a week of mouths and beckett!’. She attached a YouTube clip of Not I (1972), Beckett’s play featuring a lit-up character MOUTH speaking on a dark stage.

Isn’t it totally humane and reasonable to find it sad (difficult even, yes!) to not drink for a few days? My Dad found it worrisome. But Beckett was miserable in convalescence, and weaned himself a.s.a.p. back into his preferred lifestyle via tiny gifted Champagne bottles from painter Henri Hayden and his wife Josette. Mom and I went for a Sunday walk, and a Beckett scholar recommended me Whiteknights Lake around which to peregrinate Beckett-ishly.

The NHS is in tatters Sky News broadcasts about it perpetually at the Sure Hotel by Best Western Reading, with guidance on how to talk about health with your loved ones. Vox-pops probe health’s socio-economic determinance, as the public is asked to recall advantageous and disadvantageous experiential aspects of their postcode-locations.

As my gums were healing, archive fever gripped. I endeavoured calming myself with the Beckett Centre’s print-version archive catalogue, but only spied proliferate items to impossibly look at. I was relieved to learn Eimar McBride was overwhelmed by the archive’s quantities. Going through my Addendum-specific notes I’d started compiling I came upon following: ‘Repeat repeat repeat repeat trying and trying and trying and trying, confused confused confused confused, soothe soothe soothe soothe’. God. Beckett had five or six different pairs of glasses for different activities, a consoling discovery as I’d been having to wear my own semi-optional pair 24/7 while ill at the Beckett Centre, which I left still-poorly but happy, blessed with Steven’s sympathies and plenty of word-loot from an idiosyncratic episode.

I ate a banana from the shop near the Sure Hotel by Best Western Reading. Beckett used to eat bunches of bananas, according to the Beckett Centre, as we’d eaten them along the prom on mornings before the day’s onslaught began. Android bleeped it’s constantly sunny in Aberystwyth. Beckett considered going to the Canary Islands on holiday for restorative purposes, but went to Madeira and Porto Santo alternatively.

The train back to the Welsh Riviera split without notice at Shrewsbury I swear there was no announcement I am hyper-vigilant. Realising at the last moment, I jumped off it, dropping my empty Amoxicillin packet (a litter-bug) and waited un heure for the carriage prochain. Waiting, waiting. I got home on 25th September. I like a line from Beckett’s short story ‘Dante and the Lobster’ from More Pricks Than Kicks (1934): ‘It took time, but if a thing was worth doing at all it was worth doing well, that was a true saying’. It had been a scramble, but back at MyDentist Aberystwyth my Dentist removed some of my wisdom tooth and everything healed pretty nicely.

Amy Grandvoinet is a PhD researcher in fraught avant-garde literary legacies (mainly pertaining to the contested signifier ‘psychogeography’) between Aberystwyth and Cardiff Universities. Her work can be found in SPAMzine, Content Journal, The London Magazine, Worms, The Polyphony, and elsewhere (click linktr.ee/amy_k_grandvoinet for more). She is part of Literature Wales x Disability Arts Cymru’s Reinventing the Protagonist 2024-5 writing programme, and is a co-founder of think.material Press.

What’s Sam got to do with psychogeography?

What’s Sam got to do with psychogeography? Alexander Trocchi and Samuel Beckett from Paris 5, 6 & 7e to Reading

Amy Grandvoinet

AHRC-funded PhD student

An aeon article with web-address ending ‘psychogeography-where-writers-should-now-fear-to-tread’ features just one snap: a gigantic portrait of Samuel Beckett on a Notting Hill wall (1). The article regrets psychogeography’s diminished status today as a formulaic literary genre, whereby writers traverse urban landscapes and scribe about them whilst celebrating an avant-garde canon. Psychogeography’s not what it was, says aeon, tired and depoliticised since its radical origins in the 1950s and 60s. Defined by Paris-based Lettrist and Situationist Internationals (1952 to 1957 and 1957 to 1972 respectively) exécutif Guy Debord as ‘the study of the precise laws of the specific effects of the geographical environment, whether consciously organised or not, on the emotions and behaviours of individuals’, ancien psychogeography wasn’t a creative writing prompt, but a means of analysing the social production of space in an immediate post-war milieu aligned with Marxist sociologist Henri Lefebvre (2). En fait, Lettrists and Situationists were very sceptical about artistic production under the hyper-commodifying global order they dubbed ‘the Spectacle’ (3). Beckett’s position within this picture is left silent; aeon mentions him no further beyond the snap-caption, yet Beckett was significantly embroiled in the Rive Gauche worlds from which psychogeography hatched.

For Lettrists and Situationists, a ‘psychogeographer […] explores and reports on psychogeographical phenomena’ (4). It is important to note Lettrists and Situationists did write occasional literature (albeit sardonically) relating to their psychogeographical work as such, and there were some artists they believed to be good. Beckett was one of them. In her ‘Preface in the Guise of an Autobiography (or Vice Versa)’ to the recent English translation of La nuit (1960), Michèle Bernstein, first wife of Debord and co-founding Lettrist and Situationist, cites ‘our Beckett’ outlining the complex inspirations behind her own deviant novels (5). A distant influence? A covert acquaintance? It is extremely unlikely Beckett identified as a psychogeographer, and one of my PhD supervisors (a Lettrist-Situationist specialist) confirms he’s found not much of Beckett in the field, but assumes they all must have crossed paths at least now and then. A Beckett-scholar friend tells me it’s notoriously tough to locate Beckett’s encounters with others in Paris as, of course, people met everywhere in-person often spontaneously. It is fairly well understood, though, that Beckett was friends with Alexander Trocchi, member of both Lettrist and Situationist Internationals and editor of little magazine Merlin and Collection Merlin which published some of his most renowned Anglophone fiction in 1950s paʁi.

I wanted to come to The Samuel Beckett Research Centre (hereafter the Beckett Centre) to learn whether anything in the Beckett Collection at Reading University’s Archive explicitly or implicitly evidences any psychogeography utterances between Beckett and Trocchi or otherwise. Funnily enough, I grew up nearby, twenty minutes down the A329(M) in a New Town called Bracknell, just the kind of urban development the mid-century Parisian Left Bank’s intelligentsia lamented as the epitome of ultra-functionalist Corbusian ‘machines for living’ civic designs, optimising Capital and not much else. Psyched. I knew Trocchi partook in the dérive, i.e. observing the city à pied, with Debord (‘I remember long, wonderful psychogeographical walks […] with Guy’) and Beckett is apparently famous for street walking (Steven Matthews, the Beckett Centre’s director, immediately recalled footage of Beckett drifting through Berlin as we planned my visit, and more than three friends readily commended Beckett’s sun-tanned imago cavorting down boulevards) (6). But besides any investigative walking, as I got them both Trocchi and Beckett were concerned generally with questions like: where are our bodies situated, and how? what are their capacities, or incapacities, and why? how might we orientate ourselves under present historical circumstances?

Much of the Beckett Collection is archived in a big brick box at the Museum of English Rural Life (MERL), University of Reading London Road Campus. Steven laughed Beckett would have found that hilarious. Steven and I met on Tuesdays, and remarked how all that Paris activity’s all locked away now . . .

But nuh-uh! People keep getting stuff out and doing stuff with it. See the Beckett Centre website’s Projects, Creative Fellowships, Talking Beckett Series, and Beckett Forum pages, and also Tolka Issue 7 (7).

Aside from the big brick box, the Beckett Centre is essentially a conceptual entity. There are no glass sliding doors announcing the Samuel Beckett Research Centre in frosted sans-serif font, no gift-shop selling Samuel Beckett Official Merchandise such as rubbers and pencils and postcartes. Indeed no Wonderful World of Samuel Beckett theme-park aesthetic as another of my PhD supervisors jestfully conjectured. Still, magnificent photographs of Beckett and austere scenes from his plays are mounted around the MERL Reading Room, and James Joyce’s fountain pen accessorised with a Finnegans Wake (1938) charm is displayed in a cabinet in an understated entrance foyer. Prior to arrival, I’d searched the Beckett Collection for ‘psychogeography’ via the Online Database yielding zero result, so had entered ‘trocchi’ and ‘merlin’ and ‘walk’ alternatively, which invoked over thirty items. Lots (Steven’s recommendation was music and coffee against archive fever). James Knowlson’s heroic authorised biography Damned to Fame: The Life of Samuel Beckett (2014) would be permanent company at my desk (No. 1) across the semaines deux, while cardboard tray batches of called-up artefacts awaited me daily (thank you Michele, thank you Emma). I’d examine siphonings from the big brick box at the ephemeral Beckett Centre 9.30am til 4.30pm Tuesdays to Fridays, then continue to immerse myself in Beckett’s sentence-outputs at the Sure Hotel by Best Western Reading in a cell-like room (which of course felt ‘Beckettian’) into the night (8).

So it began. Ten working days (more-or-less) of questful delving, hoping to better-place Beckett within, or outside of, Trocchi’s psychogeographic-minded coterie circles. What follows is a conglomeration of information discovered at the Beckett Centre organised into nine locations somewhat shared, each living in Paris 1937 to 1989 and 1949 to the late 1950s, by Beckett and Trocchi. Biographic info is mostly taken from Knowlson’s all-hallowed Beckett Bible and from Andrew Murray Scott’s more controversial Alexander Trocchi: The Making of a Monster (2012). Copyright is massive at the Beckett Centre, so my sharings from Beckett Collection artefacts can only be limited and confined to paraphrase, but their archival whereabouts is duly referenced so that if you really want to, you can go to the Beckett Centre and enjoy their gospel directly. Read on if you have any remote interest in continuing to find out about Beckett in the context of psychogeography, or psychogeography in the context of Samuel Beckett.

37 rue de la Bûcherie (Librairie Mistral)

Trocchi and his then-girlfriend Alice Jane Lougee (Jane) set up Merlin in 1952, and its HQ was the now-cult-followed Shakespeare & Company Bookshop at 37 rue de la Bûcherie Paris 7e opposite Notre-Dame. It may not have been selling cronuts and matcha lattes, but was open – as Librairie Mistral – weekdays midday-to-midnight and Sundays for tea from 1951. Librairie Mistral’s founder, George Whitman, changed its name in 1964 to celebrate William Shakespeare’s four-hundredth birthday and in homage to Sylvia Beach’s original Shakespeare & Company Bookshop at 12 rue l’Odéon, a hot-hub for émigré writers such as Gertrude Stein and James Joyce, until its closure in 1941 during World War Two (9). Beckett had gone there, and was part of the scene, pals with Joyce whose Finnegans Wake he assisted on. By the time Trocchi got to the City of Light, things had moved intellectually on. In Paris Interzone (1994), James Campbell says Merlin was a new publication distinguished by ‘a particular intelligence’, intending to surpass influential existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre’s Les Temps Modernes established in 1945 to ‘give an account of the present, as complete and faithful as possible’ (10). Trocchi, like Beckett, was well-connected, soon hanging out with the razer-sharp Lettrists (he appears at 6:11 in Debord’s film Critique de la Separation (1961) which documents their early-50s psychogeographically-guided proceedings) (11). Like Beckett’s, Lettrists approved Trocchi’s writing as of decent integrity. A pale yellow folder in the Beckett Centre packed with 1990s missives from Jane to Knowlson detail Merlin’s early printing logistics at Imprim’ier Mazarie nearby and Fonteney-aux-Roses in the suburbs: Merlin #1 came out in May, and Merlin #2 in Autumn. Merlin #2 features co-editor Richard Seaver’s essay ‘Samuel Beckett: An Introduction’, penned after snatching up Beckett’s Molloy (1951) and Malone meurt (1951) from Les Editions de Minuit’s shop window at 7 rue Bernard-Palissy (12).

Merlin wanted Beckett. Copies were sent to he and Jérôme Lindon, who’d told Seaver a certain English novel of his still sought publication. Merlin was by no means a Lettrist wing (they had their own periodical Potlatch), but loosely associated and with kindred objectives, but reading Beckett’s early writing in mind of its psychogeography-ish appeal seems fructiferous. Before Molloy and Malone meurt, in which old ill and woeful Molloy is failingly searched for by detective Moran then Malone reflects on his deathbed, Beckett’s More Pricks Than Kicks’ (1934) short stories comment abundantly on contemporary environs and the constituent human moods they effect. Dublin-based young man Belacqua (named after a minor character in Dante’s Divina Commedia (1321)) escapades with familiars eating lobster gorgonzola toast, remarking ruins and Portrane Lunatic Asylum, reading, feeling like a ‘sad animal’, and attempting to tackle ‘the Furies’ by going hither and thither to no avail (13). Beckett had just undergone a stretch of difficult psychotherapy in Belsize Park. In Murphy (1938), Beckett’s first novel, Murphy’s adrift in London, and withdraws from life to a troubled rocking-chair. I found a piece in The Stinging Fly where Cathy Sweeney reads First Love (1973), written in 1943 during his service in the French Resistance, and detects Beckett’s ability to offer ‘the being’ of characters uniquely (14). Conor Carville, a colleague of Steven’s at the Beckett Centre, deems some of Beckett’s tôt poetry ‘almost psychogeographical’ – see for instance lines on Saint-Lô, where Beckett was stationed at the Irish Red Cross Hospital in 1945, as ‘bombed out of existence in one night’ bringing ‘the trauma of a new situation encountered face to face’ (also documented as ‘The Capital of Ruins’ in the Irish Times) (15). Beckett’s foci matched perfectly what Trocchi’s debut editorial classified ‘good writing with a social function not aesthetically compromised geared up to treat an Orwellian now’ (16).

Dépôt at 8 rue du Sabot

Beckett wrote to Trocchi in February 1953: ‘Watt is at your disposal whenever you like. I’ll have it round as soon as I get back to Paris’ (17). Trocchi and Jane were living rent-free in Seaver’s house, an ex-banana-drying warehouse in Saint-Germain-des-Près. They waited. Seaver remembers: ‘We had all but given up when one rainy afternoon, at the rue du Sabot banana-drying dépôt, a knock came at the door and a tall, gaunt figure in a raincoat handed in a manuscript in a black imitation-leather binding, and left us almost without a word. That night half a dozen of us […] sat up half the night and read Watt aloud, taking turns till our voices gave out. If it took many more hours than that it should have, it was because we kept pausing to wait for the laughter to subside’ (18). Hourra! On a muffly CD at the Beckett Centre labelled ‘Hardly used in the biography or anywhere else’, Jane remembers to Knowlson that night too, and says Merlin writers often gathered at 8 rue du Sabot because Trocchi was an excellent cook (contrary to mine and Sharon Kivland’s hypotheses), but that when Beckett visited he only ever stood in the doorway (19). Jane seems to think Beckett was lovely, real, old-fashioned, and quite unlike the rest of them but sympathetic. In a letter to literary agent George Reavey in May 1953 Beckett mentions ‘the Merlin Juveniles’.

Watt (1953) would be published on the last day of August by Collection Merlin, an imprint of Olympia Press governed by Maurice Girodias, who Jane says Beckett disliked. Girodias’s papa was Jack Kahane of Obelisk Press, for whom Beckett had almost translated the Marquis de Sade (did he see Debord’s screening of Hurlements en faveur de Sade (1952) at 17 Place du Trocadéro?). Trocchi, Christopher Logue, Austryn Wainhouse, and others from Merlin wrote erotic or ‘db’ (dirty books) fiction under Olympia Press’s Traveller’s Companion series to buoy up funds (so did ex-Situationist Raoul Vaneigem with L’Ile aux delices (1979) much later with Éditions du Bébé Noir). Beckett’s Watt was differently bodily-oriented. The extract he chose as a preview for Merlin #3, Winter 1952-3 (one of four issues held by the Beckett Centre), depicts Watt’s observations of master Knott in mundane hilarity: ‘As for his feet, sometimes he wore on each a sock, or on the one a sock and on the other a stocking, or a boot, or a shoe, or a slipper, or a sock and boot, or a sock and shoe, or a sock and slipper, or a stocking and boot, or a stocking and shoe, or a stocking and slipper, or nothing at all’, and so on. And ‘Here he stood. Here he sat. Here he knelt. Here he lay. Here he moved, to and fro, from the door to the window, from the window to the door; from the window to the door, from the door to the window; from the fire to the bed, from the bed to the fire; from the bed to the fire’, and so on. And then on Sunday Mr Knott moves his furniture about in an incessant feng shui which continues Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday and répéter alllllll the way to ‘Sunday week’ then ‘Friday fortnight’ before closing – ‘And then, while he put on the one, the black boot, the brown shoe, the black slipper, the brown boot, the black shoe, the brown slipper, on the one foot, he held the other tight, lest it should escape, or put it in his pocket, or put it in his mouth, or put his foot upon it, or put it in a drawer, till he might put it on, on the other foot’ (20). Watt’s room is bare and dingy with a single window through which a racecourse is visible, and stars Watt gazes at when he cannot sleep. In a ‘Letter from Paris’ in Nimbus Quarterly, Summer 1953, Trocchi wrote: ‘Beckett’s characters (Molloy, Malone, Watt) are so inactive, so vegetable, that they are also in a queer and disquieting way in revolt’ (21). As states Andre Furlani, Beckett’s characters are never bourgeois flâneurs, Surrealist déambulatists, or psychogoegrapher-dérivers (22). Their tragi-comically compromised subjectivities dramatise the atrocities of human thingification.

Merlin #3’s announcement of upcoming Watt (twenty-five signed copies lettered A to Y and one-thousand-one-hundred regular numbered copies payable in francs or pounds or dollars) praises Beckett in comparison to Franz Kafka (another writer Lettrists and Situationists broadly condoned). Trocchi’s editorial is busy correcting ‘art for art’s sake’ accusations, Seaver addresses politics head-on in an essay ‘Revolt and Revolution’, and at the back there’s a chance to order loads (many if not all Lettrist-Situationist approved) more books by Guillaume Apollinaire, Louis Aragon, André Breton, Albert Camus, Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette, André Gide, Julien Gracq, Comte de Lautréamont, Lefebvre, André Malraux, Marcel Proust, and Sartre, via Librairie Mistral. Merlin #4, Spring-Summer 1953 (two of four issues held by the Beckett Centre), celebrating ‘beckett samuel beckett samuel beckett samuel beckett samuel beckett samuel beckett samuel’ across its back-cover touting the now-available tome (23). Beckett wasn’t joyeux, though, ruing the ‘awful magenta’ cover in a letter to Reavey in September, as well as mass (eighty) spelling and typographical errors including an entire omitted sentence on page nineteen (Beckett’s miffed annotations in his own personal copy (number eight-five) can be viewed at the Beckett Centre from a special foam plinth) (24).

Chez Moineau, 22 rue du Four

Drinking, thinking, and writing was a classic combo in Saint-Germain-des-Près, already becoming a tourist destination as such. I can find no verification Beckett mixed with Lettrists and Situationists at their favoured café Chez Moineau (22 rue du Four), though his frequentations of more upmarket Café Deux Magot, Café de Flore, Closerie des Lilas, the Dôme, the Cigogne, the Iles Marquises, Chez Tournon, La Coupole et cetera are well-documented (Knowlson’s biography indexes over thirty entries under ‘drinking’). Another founding member of the Situationist International and solo London Psychogeographical Society component also living in Paris in the 1950s and 60s, Ralph Rumney, remembers Moineau’s as ‘more or less the only place we were welcome or at least well received’ being ‘extremely disreputable, scruffy, scurrilous, and penniless’ (25). Did Trocchi even mingle here, always turned-out and with money on him says Logue? They weren’t close, but Rumney knew Trocchi as editor of Merlin (which he describes as ‘a magazine of the Anglo-intellectual expat scene in Paris’) and as courteous (‘he put me up’). Beckett’s and Rumney’s link is more convoluted, and pertains to some darkness. At the Beckett Centre, in a Peggy Guggenheim folder is Rumney’s obituary from 2002 titled ‘Ralph Rumney: Co-founder of the Situationist International accused by Peggy Guggenheim of murdering her daughter’ (26). Pegeen died of an overdose in 1967 while married to Rumney since 1958, and having birthed their child Sandro. Peggy’s reputation as patron and affair-monger came with toxicity – ‘You’re f***ing your way up to quite a collection’ said she to Pegeen who Rumney simply gifted a painting Peggy’d wanted to purchase. Beckett and Peggy had dallianced in the late 1930s; the folder also contains photocopies of pages from Guggenheim’s mémoire about it, plus a French ELLE (No. 2273 Juliett 1989) article on she and her sex-life with an image of Beckett described ‘L’écrivain irlandais est très grand, tres timide, tres mélancolique, jeune (il a 31 ans) et tres séduisant’. What Beckett later thought of it all seems crucial in ways I can’t hope to know and don’t wish to gossip about. Anyway, Beckett and Trocchi, according to Jane, met to discuss writing matters at a private bar which remains unidentifiable (quite right).

École Normale Supérieure Paris 75005

Beckett, Trocchi, and the Lettrists and Situationists perhaps had in common an appetite for meaningful thought outside the academy (and not always in pubs). Both Trocchi and Beckett came to Paris’s literati post degree-level study, English & Philosophy at Glasgow University and French & Italian at Trinity College Dublin. After a lecturing stint at the École Normale Supérieure, 45 rue d’Ulm 1928 to 1930, Beckett realised an academic profession was not for him, though his hunger for learning hardly waned. Steven and Matthew Feldman recently collated reams of ‘Philosophy Notes’ Beckett made over his lifetime (ancient Greeks through to nineteenth-century nihilism) using his ‘note-snatching’ method, considering having not covered a philosophical canon as an undergraduate a ‘serious defect’ (27). Although Beckett’s notes are fairly irreverent (sometimes scribbling expressions like ‘Tra-la-la-la’ and allegedly quipping ‘I never understand anything they write’), Beckett was philosophically-dedicated, his interests particularly gravitated toward the psychoanalysis he absorbed totally. More non-swottish scrawls were found alongside these papers in a trunk in Beckett’s cellar posthumously from gallery visits, including on Claude Lorrain’s paintings which Lettrists and Situationists loved (28). Trocchi was similarly passionate. Edwin Morgan regarded him a most talented (and maverick) student, and a travel scholarship funded his move to Paris following Royal Navy conscription 1943 to 1946. Trocchi later schemed project sigma as ‘a worldwide linking up of intellectuals, poets and writers to effect a revolutionary transformation of Western Society’ avec free universities, outlined in ‘A Revolutionary Proposal: The Invisible Insurrection of A Million Minds’ in the Situationist journal Internationale Situationniste (29). Its ideas still iterate now (30). The Situationists were instrumental in the student and worker uprisings of May ’68, occupying Strasbourg, Nanterre, and Sorbonne universities, where Beckett appears by a statue of Auguste Comte in one of few photos in Knowlson’s biography (31).

6 rue des Favorites

Beckett invited Trocchi to his apartment at 6 rue des Favorites (where he lived with Suzanne Déchevaux-Dumesnil), arm’s length from Saint Germain in 15e down long, long rue de Vaugirard. It was high up, desk at the living-room window (Knowlson tells us Beckett ‘felt very miserable when he was deprived of light’) next to which was a waste-paper basket keeping a bottle of whisky. Steven joked Beckett lived on whisky-spiked French onion soup at some point probably (I immediately buy tins of Lidl French onion soup returning to Aberystwyth). Murray Scott says Beckett had Trocchi round often and once even made him ‘a breakfast of kippers’ (32)! Fuel for psychogeography. Jane reminisces a relaxed hour in 1953 in which she and Trocchi were at Beckett’s, talking about how funny it was Jane’s dad lived in Limerick in Maine while there was a Limerick in Ireland. Jane divulged she’d sold her car to help get Merlin going in addition to their tutoring and translating and Trocchi’s dbs, and Beckett spoke of struggles he’d had getting Watt anywhere in England. It is a pleasant vignette. Trocchi was at this time completing his novel Young Adam (1954), on Glasgow-Edinburgh barge-skipper assistant Joe, soon to be published in France under pseudonym Frances Lengel due to illicit content (it’s now listed in The Scottish Book Trust’s Best 100 Scottish Books of All Time) (33). In the same folder as Jane’s correspondence with Knowlson, there’s a letter from Beckett to Trocchi I can hardly make out because the handwriting’s sooo relax’dly slanted, but which seems to thank intimately-addressed dear Alex for a letter he’d sent, and that Young Adam is very good c o n g r a t u l a t i o n s.

Knowlson says Beckett found Paris increasingly difficult from the 1950s, too many appointments and too much epistolary upkeep in a city he referred to as ‘petrol chamber’. Incidentally, car proliferation was a key motivation for the instigation of psychogeography, a recurring gripe in Lettrist and Situationist bulletins (34). Paris was changing rapidly. Hôtel particulieurs slum the Marais (where Debord and Bernstein had temporarily nested) was disappearing, by 1968 historic Les Halles market had been demolished (replaced by an RER terminal plus shopping-and-entertainment facilities), Beaubourg in 1969 became the crass Pompidou Centre, and in the 70s peripheral grands ensembles (for example Sarcelles) had sucked the working-class populations out of the inner-city where white-collar residents doubled (35). Beckett and Suzanne had a house built in Ussy-sur-Marne in the early-50s, forty miles (sixty kilometres continentally) North-East of Paris, where they’d bolt to regularly. While at the Beckett Centre, I forayed into Reading town-centre to assess the changes there since my pre-2011 Berkshire-zones life: all still locked in a ring of A-roads and roundabouts, there is no more emo-destination Shakeaway Milkshake Bar on Union Street (but still Timpsons and phone shops e.g. PHONE CITY), smashed up Edwardian Harris Arcade just about manages to sell tobacco and vinyl though mainly is derelict, a gentrified Brixton/Peckham/Shoreditch-style shipping-container street food conglomeration (Blue Collar Corner) mushrooms in an abandoned yard on Hosier Street, millennium-2000 shopping centre The Oracle (once glaringly glitzy) looks pretty drab.

Party-Time at 5 rue Vaneau

Five photographs from a Merlin party, December 1953, in the Beckett Centre’s Merlin file, are beguiling (36). In spite of being Merlin’s blue-eyed boy, Beckett’s as-far-as-is-tellable not present. As well as Watt, Minuit had now released L’Innommable (1953), third in the so-called trilogy after Molloy and Malone meurt, too. The party was on a Wednesday (9th) 5-7.30pm at 5 rue Vaneau Paris 7e, à la maison de Important-Author enthusiasts Mr and Mrs Clements. Photo I, Trocchi is broad and charismatic in tailored suit (herringbone?) talking to Seaver also dressed smartly in jacket-and-tie before a three-flamed candelabra and large metal clock. Photo II, Trocchi smirks with Jane who laughs in off-shoulder black dress and drop-pearl earrings; they sit on a satin floral sofa, both wearing Merlin logo-pins (black silhouettes of the falco columbarius or pigeon-hawk known for its vision and boldness and formidability). Photo III is Trocchi, Seaver, and George Plimpton of The Paris Review. Photo IV, Eugène Ionesco and Trocchi admire Merlin’s latest issue. In Photo V, everyone (still no Beckett) comes together by a table of snacks and beverages. Where was Beckett instead? Strolling the Jardin du Luxembourg or Parc Montsouris? Playing tennis on the tennis-court, or Hayden or Schubert on the piano, or chess with Marcel Duchamp amid bepop and jazz and smoke-puffs? Enjoying sweet ‘square words’ word-game invented with colleague and lover Pamela Mitchell who he’d just met? Dining at the Les Invalides Air Terminal restaurant on ham spinach sandwiches and Beaujolais? Not going to the zoo which he considered distasteful? Knowlson provides idiosyncratic intel infinitely superior to Sky Arts’s 2023 biopic scoring a way-too-generous forty-two percent on Rotten Tomatoes (37).

The English Bookshop, 42 rue de Seine

It’s unclear why but Merlin had moved their address in Autumn 1953 to the English Bookshop at 42 rue de Seine, run by proprietress Gaïte Frogé from Brittany. It was smaller than Librairie Mistral and more discriminate in stock (classics and new avant-garde). Merlin #5 (three of four issues held by the Beckett Centre) from this new location presents an excerpt from Collection Merlin’s forthcoming English translation of Molloy that Beckett and Patrick Bowles (‘an English inebriate living in Majorca’ who’s ‘pleasant to work with’ wrote Beckett to Pamela November 1953) had started and would finally finish January 1955 in an arduous process Pim Velhurst and Dillen Wout have nobly traced out of obscurity (38). December, Beckett wrote again to Pamela sick with Molloy and wishing it would snow. Merlin #5 opens advertising Collection Merlin’s already-available products (incl. Watt) and pending publications (incl. Molloy), followed by another Trocchi editorial emphasising the ‘serious writer’ over ‘popular writing’ (a Lettrist-Situationist-esque distinction) (39). The Molloy tract’s illustrated by a mad drawing of a mad man with mad hair and mad v-neck top and mad fish-like hands, and opens from the novel’s paragraph premier: ‘I am in my mother’s room. It’s I who live there now’. External landscapes which uncanny figures ‘A’ and ‘C’ negotiate ‘and not only that but the within, all the inner space one never sees, the brain and the heart and other caverns where thought and feeling dance their sabbath’ unfold, before the passage finishes twenty-three pages on with a burning sulphur and phosphorous horizon Molloy is bound to. Molloy, Malone Dies, and The Unnameable (Beckett translated the second two himself) are known as tales of profound lostness, loneliness, despair and panic (40). They capture the mass schizophrenia of a traumatised epoch. Psycho-geography?

Merlin’s penultimate issue, #6 (four of four issues held by the Beckett Centre, and now declaring itself ‘one of the few serious international reviews’ which ‘faithfully exposes the intellectual climate on both sides of the Atlantic’) printed Beckett’s and Seavers’ ‘The End’, originally ‘La Fin’ in Les Temps Moderne, in Summer-Autumn 1954. Strangely, Merlin #6’s back-cover is a perfume ad – le Meilleur parfum du monde (41). Surely a hoax? In a huge editorial ‘words and war’ pages three-to-five cont. two-hundred-and-nine-to-two-hundred-and-seven, Trocchi berates ‘the East-West deadlock today’ and news discourse that lulls listeners into binary thinking, a scenario to be busted if global sanity’s to be gained outside of the (nuclear) war economy (writers should not be ‘literary courtiers of this new Versailles’ but urgently exteriorise ‘emotively significant psychological states’ coterminous with ‘affective’ environments to encourage reason). ‘The End’ starts on page six (‘They dressed me and gave me money. I knew what the money was to be used for, it was my travelling expenses. When it was gone, they said, I would have to get some more, if I wanted to go on travelling’) and lasts eighteen pages depicting disappearing buildings and morphing slogans and a river that seems like it’s going backwards and more, amplifying l’horreur claustrophobie. Trocchi’s short story ‘The Rum and the Pelican’ lies adjacent – a man is aware of his ‘gradual decay’ as the planet’s ‘going from bad to worse’, plot hinging on a regular bus-route that passes tinglingly a colossal Martinique poster-woman. Merlin #6 closes on black and red uprising stick-men, and notification of an Abbaye Rotisserie with medieval atmosphere event at 22 rue Jacob: seventy years on scrolling Instagram a Story I glimpse promotes a Techno Medieval Banquet Night happening in Leeds this October, and much seems undifferent.

There’d been hullabaloo around paying Beckett for Watt (late), translating Molloy (long), and publishing ‘The End’ (full of mistakes). At the Beckett Centre, there’s a Beckett-Merlin correspondence folder where you can read all about it (42). August 1954 Beckett wrote to Pamela ‘Have written a stinker to Trocchi. Fed up with them’. Basically, though, it all got resolved or blew over. Trocchi and Beckett were not ‘on speaking terms’ for a bit, as Beckett wrote to Barney Rosset of Grove Press in October, but Beckett and ‘the Merlin lads’ were soon out together for dinner when he wrote to A. J. Leventhal November the following year (after the final issue of Merlin, #7, Summer-Autumn 1955), and in 1958 Beckett wrote to Seaver that Logue had been over ‘in good form’ and that he and Bowles (whose recent poems he ‘liked very much’) had met for lunch in the last fortnight, adding ‘Remember me to Trocchi if you write to him’ (43). Trocchi left Paris for New York in the late 50s and completed Cain’s Book (1960), which quotes Beckett directly at length (‘This time I know where I am going’ and then much about playing and to be able to play alone even in the dark and that to ‘To have been able to conceive such a plan is encouraging’) (44). Further, ‘stumbling across tundras of unmeaning, planting words like bloody flags in my wake’ might be a reference to Beckett’s poem after Watt (‘of the empty heart / of the empty hands / of the dark mind stumbling / through barren lands’). Beckett continued to read and appreciate Trocchi’s work; he wrote to Seaver in 1958 saying he’d read a portion of Cain’s Book in Evergreen and ‘liked it very much indeed’ and to Judith Schmidt (Rosset’s assistant) on having read it all that it was ‘Very good indeed I think. Shall be writing to Trocchi next semi-lucid intermission’. Too, Knowlson told Jane on the muffly CD he read Cain’s Book because Beckett instructed him so.

Théâtre de Babylone, Boulevard Raspail

So… no explicit recorded utterance of psychogeography between Trocchi and Beckett, no hard evidence Beckett ever met any Lettrist or Situationist other than Trocchi. Any further conversation and path-crossing can only be speculative. Steven said the Merlin boys must have attended the debut of En attendant Godot (1952) at Théâtre de Babylone 38 Boulevard Raspail back in January 1953 – maybe all of the Lettrists were there too, debriefing afterwards on its psychogeographical acumen? Applauding Beckett’s shrewd hijacking of Spectacular culture? I heard in the archives Beckett was gutted for having had to turn down New York Broadway’s proposition pitch that Buster Keaton and Marlon Brando play Didi and Gogo. The Waiting for Godot (1954) West-End team (Ben Whishaw, Lucien Msamati et. al.) were at the Beckett Centre a mere week prior to my visit to prepare for their 2024 Haymarket hijinks.

Steven told me Beckett’s attention to spatiality is typically most-recognised in respect to his dramatic works (Rónán McDonald mentions ‘the spare Beckettian stage’ as the paragon). Beckett in theatre is maybe metteur en scene most obviously. A scene-setter, a scientist experimenting with conditions and outcomes. Were Situationists in the audiences of Fin de partie (1957) or Krapp’s Last Tape (1958) or Oh les beaux jours (1963) or Play (1964) thinking so? Beckett is fastidious in his stagely directives. In Footfalls (1976) a mother (‘Woman’s voice (V)’) and daughter (‘May (M)’) poise between ‘(pacing)’ and ‘(Pause.)’-ing for twenty-five minutes according to precise step-sequences, set scant (Steven recommended its draft manuscripts jammed, on gridded paper, with Beckett’s equation and diagram workings-out) (45). At the end, V asks M ‘Will you never have done . . . revolving it all? (Pause.) It? (Pause.) It all. (Pause.) In your poor mind’… Probably not?! Beckett’s workings out for QUAD (1981) for German telly are similar, where Beckett maps a choreography of four numbered and colour-lit percussion-accompanied players (preferably ballet-trained) in hooded floor-length gowns round and intersecting at diagonal lines a six-pace-sided square (46). John Green gave a conference paper on QUAD and psychogeography in 2020 at the National University of Ireland, Galway, which is not readily available online but its abstract states: ‘Samuel Beckett and Guy Debord both experienced walking as therapeutic exercise, a psycho-physical conduit to creative revelation’ and that ‘Walking as act, as dream, as memory, defines the consciousness of Beckett’s characters’ – keywords Theatre, Samuel Beckett, Psychogeography, Situationists, Actor Training (47). Curious.

I browse the shelves of the Beckett Centre’s Open Access Library Room G07 where a sign reminds you Please ask for assistance if required Please ask for permission before taking photographs, and generate two book-stacks Michele tells me are the tallest she’s seen in two years (#ResearchVirtueSignal). There’s scholarship on: Beckett and wandering, Beckett and home, Beckett and metaphysics, Beckett and void, Beckett and cosmology, Beckett and geometry, Beckett and trauma, Beckett and bodily malfunction, Beckett and prosthetics, Beckett and mechanics, Beckett and love, Beckett and abjection, Beckett and catastrophe, Beckett and slow violence, Beckett and psychoanalysis, Beckett and Ireland, Beckett and diaspora, Beckett and the future, Beckett and comedy, Beckett and mood, Beckett and dream, Beckett and alienation, Beckett and the tragicomic, Beckett and medievalism, Beckett and heroes, Beckett and joy, Beckett and healing, Beckett and hyper-subjectivity, Beckett and ontology, Beckett and the extra-linguistic, Beckett and semiotics, Beckett and Leiblichkeit, Beckett and the extra-socially social, Beckett and the angelic, Beckett and truth, Beckett and materialism, Beckett and sans frontières, Beckett and Romanticism, Beckett and refuge, Beckett and human rights, more. I particularly liked Bert O. States’s title Great Reckonings in Little Rooms: On the Phenomenology of Theater (1985). Il n’y a pas beaucoup de temps.

38 Boulevard Saint-Jacques

It seems unlikely Trocchi visited Beckett’s new flat at 38 Boulevard Saint-Jacques, where he moved with Suzanne in 1961. By that time, Trocchi was in New York and San Francisco, getting into trouble with the law and narrowly evading imprisonment (the Situationists wrote to his defence in ‘Hands Off Alexander Trocchi!’), then would live in London for the rest of his days (48). After Cain’s Book, on junkie life and writing as a scow on the Hudson River, Trocchi didn’t publish loads else. sigma garnered some interest for a while; its Sigma Portfolio digest, featuring an updated translation of the ‘Manifesto Situationniste’ and stressing the need for enduring concentration on ‘what we call “psycho-geographic” factors’, circulated among the likes of Jeff Nuttal, Morgan, R. D. Laing, and William Burroughs in the early 1960s. In 1962, Trocchi spoke at the Edinburgh Writers Conference, and in 1965 co-compered the International Poetry Incarnation at the Royal Albert Hall starring Allen Ginsburg. Michael Horovitz’s anthology Children of Albion: Poetry of the Underground in Britain (1969) contains four poems by Trocchi, and Calder Publications, who’d become the main publisher of Beckett’s works in English, collated Trocchi’s poetic oeuvre as Man at Leisure (1972), and short fiction as The Holy Man and Other Stories (2019) posthumously. His unfinished The Long Book is unpublished. What does it do? Was Beckett reading it after he’d so enjoyed Cain’s Book?

From Floor 7 at 38 Boulevard Saint-Jacques in 14e closer to 5, 6, & 7, Beckett sat a metal desk overlooking Prisión de La Santé (where the man who near-fatally stabbed him in 1938 was briefly incarcerated) and continued to write prolifically into the 60s and 70s and 80s. Steven recommended Stories and Texts for Nothing (1967) for its jumbled and vanishing locations, reminding me of the ‘vaguening’ and ‘topophobia’ and ‘glissading’ techniques Conor mentions in his psychogeography-referencing podcast on Beckett’s poetry (note Beckett was also printed by Horovitz, his poem ‘hors crâne / something there / dread nay’ in New Departures in 1975). When May ’68 was in its full throes (the ‘Night of the Barricades’ just up the boulevard at Place Denfert-Rochereau) Beckett was poorly and could only follow closely the events in newspapers and via the radio, continuing his bilingual exertions: as well as his plays, cue for example Le Dépeupleur (1970) and The Lost Ones (1971), Pour finir encore et autres foirades and For to End Yet Again and Other Fizzles (both 1976), Company (1980), Mal vu mal dit (1981) and Ill Seen Ill Said (1982), Worstward Ho (1983). The Beckett Centre’s Worstward Ho manuscripts are on more grid-paper, designed as if for the stage, organising an ambiguous narrator’s movement in space to beget a kinaesthetic soliloquy: ‘On. Say on. Be said on. Somehow on. Till nohow on. Said nohow on. […] First the body. No. First the place. No. First both. […] Somehow in. Beyondless. Thenceless there. Thitherless there. Thenceless thitherless there’ (49). Can you believe Beckett was born on Friday 13th and Good Friday?! The weight of life, and death, and luckiness, past present and future? Both Beckett and Trocchi died in the 80s, Beckett eighty-three and Trocchi fifty-eight. Beckett is buried with Suzanne in, second only to Père Lachaise, Paris’s Montparnasse Cemetery, while Trocchi’s ashes are rumoured to be mislaid under mysterious circumstances.

Whopping thunderstorms at the archives. Beckett and Trocchi were concerned with a lot, dissatisfied with a dissatisfactory world (and absolutely fighting for the more satisfactory, felicitous, and fête). They implore: keep moving. As Beckett cantilled to Thomas McGreevy in February 1936 ‘Quando il piede cammina, il cuore gode’ (when the foot walks, the heart rejoices) (50). I think he means it metaphorically and literally, and I think the Lettrist and Situationist psychogeographers would have saluted the sentiment with vigour. If it was not possible to gauge Beckett’s awareness or unawareness of psychogeography visiting the Beckett Centre, could it be reasonable to suggest Beckett, at minimum, shared with Trocchi and the Lettrists and Situationists a psychogeographic sensibility? When Sky News Breakfast was on at the Sure Hotel by Best Western Reading at breakfast each morning, I attempted imagining just what Beckett and Trocchi might make of it all – from ongoing genocide in Gaza and Lebanon to this year’s Para-Olympics in Paris – betwixt mouthfuls of twenty-first century baked-beans and eggs. It was raining a lot now at the end of September, but all of the Beckett Collection documentations were safe in the Beckett Centre’s big brick box. Precious. Kept. As conkers fell off spiky-chestnut trees and leaves turned copper. Big big big thunderstorms and lightning huge rain. It stops, and the papillons jaunes are eleutheria in the grounds of the Beckett Centre.

(1) Will Wiles, ‘Walk the lines’, aeon, 12 Apr, 2017 .

(2) Guy Debord, ‘Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography’, Situationist International Anthology: Revised and Expanded Edition Ken Knabb ed. trans. (Berkeley: Bureau of Public Secrets, 2006).

(3) Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle Ken Knabb ed. trans. (Berkeley: Bureau of Public Secrets, 2014).

(4) ‘Definitions’, Situationist International Anthology: Revised and Expanded Edition Ken Knabb ed. trans. (Berkeley: Bureau of Public Secrets, 2006).

(5) Michèle Bernstein, The Night, 2nd edn. (London: Book Works, 2020).

(6) Merlin Coverley, Psychogeography (Harpenden: Pocket Essentials, 2010); Francesco Ghisi, ‘Samuel Beckett in Berlin – 1969’, YouTube, 20 Feb, 2015 .

(7) ‘The Samuel Beckett Research Centre’, University of Reading ; Chloé Duane, ‘FOUR RESPONSES TO SAMUEL BECKETT’, Tolka 7 (2024).

(8) See Luke Thurston, ‘Samuel Beckett’, British and Irish Literature: Oxford Bibliographies Andrew Hadfield ed. (2012), ; see Rónán McDonald, ‘Introduction’ in The Cambridge Introduction to Samuel Beckett Rónán McDonald ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

(9) ‘A Brief History of a Parisian Bookstore’, Shakespeare & Company Paris (2024) .

(10) James Campbell, Paris Interzone: Richard Wright, Lolita, O and Others on the Left Bank, 1946-60 (London: Minerva, 1994).

(11) COUNTER PUBLICS, ‘Critique of Separation – Guy Debord – 1961’, YouTube, 23 Feb, 2009 .

(12) ‘Folder entitled Lougee Bryant, Jane and Christopher Logue’ [JEK A/2/179], Beckett Collection; James Knowlson, Damned to Fame: The Life of Samuel Beckett 2nd edn. (London: Bloomsbury, 2014).

(13) Samuel Beckett, More Pricks Than Kicks (New York: Grove Press, 2010).

(14) Cathy Sweeney, ‘First Love by Samuel Beckett’, The Stinging Fly 34.2 (2016) .

(15) Samuel Beckett, Collected Poems Seán Lawlor and John Pilling eds. (London: Faber & Faber, 2013).

(16) ‘Folder entitled Trocchi, Alexander’ [JEK A/2/292], Beckett Collection.

(17) George Craig, Martha Dow Fehsenfeld, Dan Gunn, and Lois More Overbeck eds., The Letters of Samuel Beckett: 1941-56 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016).

(18) Richard Seaver ed., I Can’t Go On, I’ll Go On: A Samuel Beckett Reader (New York: Grove Weidenfeld, 1976).

(19) ‘Interviews with Jane Lougee-Bryant, and Leonard Fenton’ [JEK C/1/108], Beckett Collection.

(20) ‘Merlin: revue trimestrielle. vol. 1, no. 3 (Winter 1952/3)’ [70-MER], Beckett Collection.

(21) Allan Campbell and Tim Niel eds., A Life in Pieces: Reflections on Alexander Trocchi (Edinburgh: Rebel Inc, 1997).

(22) Andre Furlani, ‘Samuel Beckett: From the Talking Cure to the Walking Cure’, breac: A Digital Journal of Irish Studies (2017) .

(23) ‘Merlin: revue trimestrielle. vol. 2, no. 1 (1953/4)’ [70-MER], Beckett Collection.

(24) ‘Watt / Samuel Beckett. 1st ed. 1953’ Copy 2 (no. 85) [30-WAT], Beckett Collection.

(25) Ralph Rumney, The Consul: Contributions to the History of the Situationist International and Its Time, Vol. II trans. by Malcom Imrie (London: Verso, 2002).

(26) ‘Folder entitled Guggenheim, Peggy’ [JEK A/2/118], Beckett Collection.

(27) Steven Matthews and Matthew Feldman, Samuel Beckett’s ‘Philosophy Notes’ (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020).

(28) ‘Folder entitled English Galleries’ [JEK A/6/2], Beckett Collection.

(29) Alexander Trocchi, ‘A Revolutionary Proposal: The Invisible Insurrection of a Million Minds’, Internationale Situationniste 8 .

(30) The Invisible Committee, The Coming Insurrection (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2007).

(31) See Alastair Hemmens and Gabriel Zacarias eds., The Situationist International: A Radical Handbook (London: Pluto Press, 2020).

(32) Andrew Murray Scott, Alexander Trocchi: The Making of a Monster Revised and Updated edn. (Glasgow: Kennedy & Boyd, 2012).

(33) Willy Maley and Brian Donaldson eds., The 100 Best Scottish Books of All Time (Edinburgh: Scottish Book Trust, 2005); see Alexander Trocchi, Young Adam (London: One World Classics, 2008).

(34) See Guy Debord, ‘Situationist Theses on Traffic’, Situationist International Anthology: Revised and Expanded Edition Ken Knabb ed. trans. (Berkeley: Bureau of Public Secrets, 2006).

(35) Simon Sadler, The Situationist City (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1998).

(36) ‘Merlin group file’ [JEK D/1/13], Beckett Collection.

(37) ‘Dance First – 42%’, Rotten Tomatoes .

(38) ‘Part of 73 items of correspondence between Samuel Beckett and Pamela Mitchell sub-series’ [BC MS 5060], Beckett Collection; Pim Verhulst and Dillen Wout, ‘“I CAN MAKE NOTHING OF IT”: Beckett’s Collaboration with “Merlin” on the English “Molloy”’, Samuel Beckett today/aujourd’hui 26 (2014).

(39) ‘Merlin :revue trimestrielle. vol. 2, no. 2 (1953/4)’ [70-MER], Beckett Collection.

(40) Samuel Beckett, The Trilogy: Molloy, Malone Dies, The Unnamable (London: Calder, 1997).

(41) ‘Merlin :revue trimestrielle. vol. 2, no. 3 (1953/4)’ [70-MER], Beckett Collection.

(42) ‘Photocopies of Samuel Beckett’s correspondence (dated 1953 – 1954) with the Collection Merlin’ [BC MS 5039], Beckett Collection.

(43) George Craig, Martha Dow Fehsenfeld, Dan Gunn, and Lois More Overbeck eds., The Letters of Samuel Beckett: 1957-65 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016).

(44) Alexander Trocchi, Cain’s Book (New York: Grove Press, 1960).

(45) Samuel Beckett, Footfalls (London: Faber & Faber, 1978); ‘Part of Manuscripts: Drama – Footfalls sub-series’ [BC MSS DRAMA/FOO], Beckett Collection.

(46) ‘Part of Manuscripts: Drama – Quad sub-series’ [BC MSS DRAMA/QUA], Beckett Collection; see noël Claude, ‘U B U W E B Samuel Beckett Quadrat 1+2 1982’, YouTube, 11 Oct, 2012 .

(47) John Green, ‘“On the Passage of a Few People Through a Brief Moment of Time”: Utilizing Psychogeography in Creating a Live Staging of Samuel Beckett’s QUAD’, CGScholar .

(48) Guy Debord, Jacqueline de Jong, and Asger Jorn, ‘Hands off Alexander Trocchi!’ (1960) .

(49) ‘Part of Manuscripts: Prose – Worstward ho sub-series’ [BC MSS PROSE/WOR], Beckett Collectin; Samuel Beckett, Worstward Ho (London: Calder, 1983).

(50) George Craig, Martha Dow Fehsenfeld, Dan Gunn, and Lois More Overbeck eds., The Letters of Samuel Beckett: 1929-40 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016).

Amy Grandvoinet is a PhD researcher in fraught avant-garde literary legacies (mainly pertaining to the contested signifier ‘psychogeography’) between Aberystwyth and Cardiff Universities. Her work can be found in SPAMzine, Content Journal, The London Magazine, Worms, The Polyphony, and elsewhere (click linktr.ee/amy_k_grandvoinet for more). She is part of Literature Wales x Disability Arts Cymru’s Reinventing the Protagonist 2024-5 writing programme, and is a co-founder of think.material Press.

Samuel Beckett Creative Fellows: A Reading and Q & A by Claire-Louise Bennett and Simon Okotie

The Rosemary Pountney Collection at the University of Reading

The Rosemary Pountney Collection at the University of Reading

A Guest Blog by Professor Jonathan Heron (University of Warwick)

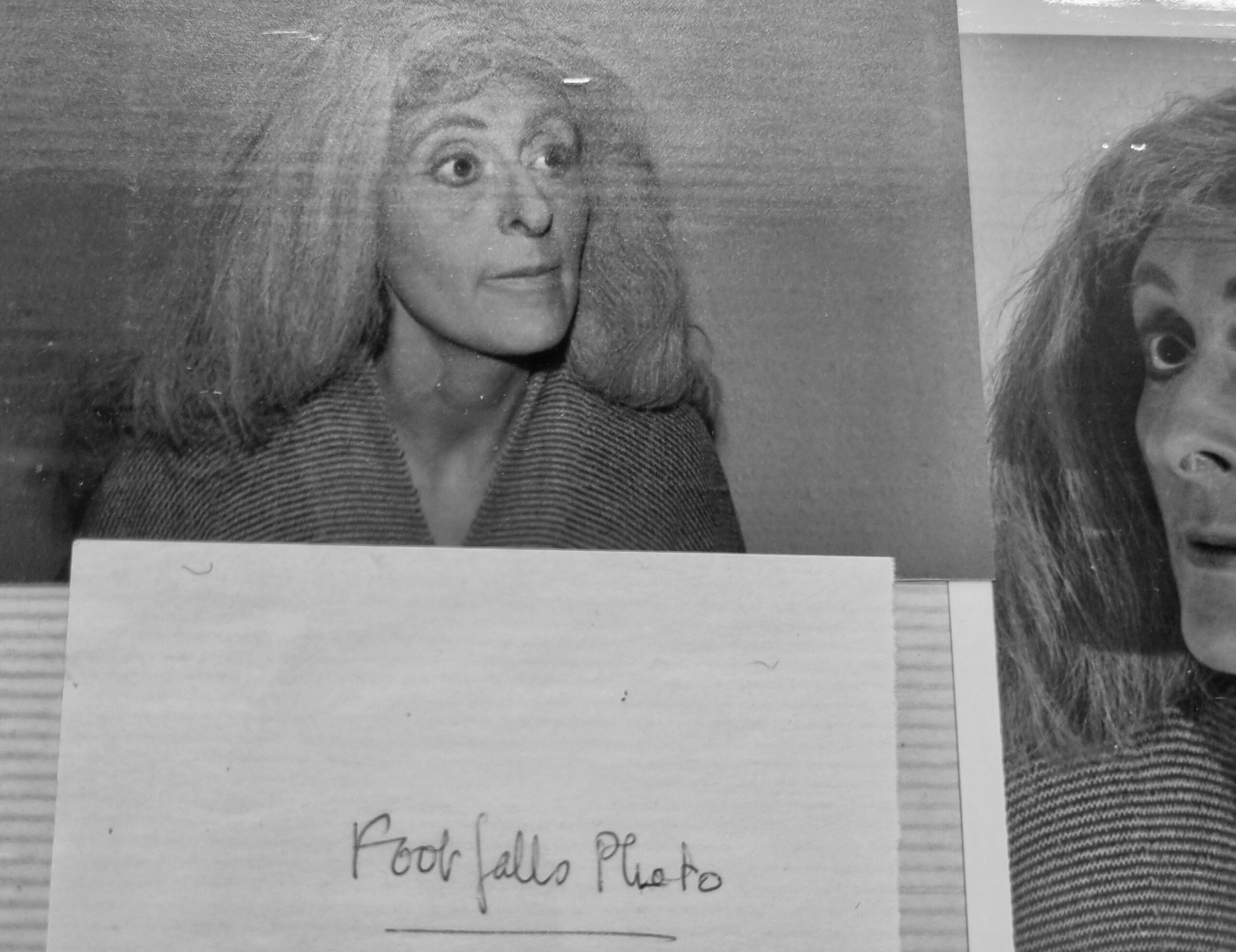

[Image 1: Production photo of Rosemary Pountney, Footfalls, 1978, image by author]

[Image 1: Production photo of Rosemary Pountney, Footfalls, 1978, image by author]

In the early hours of 20 March 2024, Rosemary Pountney’s recorded voice gave the 250,000th reading of Lessness by Samuel Beckett, some eight years since she passed. The online project End/Lessness has been running since 2017, and is available here as an indefinite memorial to her work on Beckett’s writing: [weblink].

Rosemary was a friend, colleague, mentor and collaborator who offered me guidance during my doctoral years and taught me much about performing and reading Beckett’s writing. Between 2009 and 2015, I was able to work alongside her in Oxford, Southampton, Warwick and York. In 2012 I acted as her associate director on a revival of Footfalls and Rockaby for DNS Bergen in Norway which we rehearsed in Oxford and then transferred to Trinity College Dublin as part of the annual Samuel Beckett Summer School. Throughout this period, she supported my own development as a theatre practitioner, giving notes on my theatre company’s 2009 revival of Rough for Theatre II and Ohio Impromptu, advising me on aspects of my own academic research and professional practice, and we recorded her reading of Lessness at Warwick Arts Centre in 2010, which forms the basis of the End/Lessness project, which has been described by Laura Salisbury as follows:

[The piece] uses recordings of the actor and Beckett scholar Rosemary Pountney reading out the sections from Lessness that are then played out according to computer pseudo-random generation. The possibility of ghostly endurance is particularly emphasised by the fact that the pieces of text were recorded when Pountney knew her death was imminent. But the piece is also not quite endless. Computer systems are not energyless or workless, despite an imaginary dominated by matter seemingly becoming immaterial – clouds and the ether. The material server power that underpins End/Lessness and our access to it puts back in work and organising energy into the online world and the online text; at least temporarily, it therefore opposes the thermodynamic movement towards disorder and heat death. (Salisbury, 2023)

I have written about the genesis of the work in terms of recalling Coetzee’s 1973 essay on Lessness as ‘linguistic game’, which we moved online as an ‘endless’ – If not infinite – sound installation (after Haahr and Drew, 2000):

In our collaboration with James Ball (creator of the ‘disorder algorithm’ and the website itself) we used the computational model of time to play every permutation of the sentences, without repetition, from 2017 until completion. Ball describes this process as follows: ‘to be able to create an iteration is one thing, but to be able to be sure that it hasn’t already happened is another… so the way of doing it is to make it pseudo-random… a pre-existing sequence that would carry on for a long time and would never repeat… so time’ (unpublished interview). This focus on temporal permutation, rather than textual re-iteration, resonates with Coetzee’s notion of the text as ‘linguistic game’ as well as other Beckettian permutations in performance. (Heron, 2018).

For Salisbury, our project extends our understanding of literary text in terms of its extended temporality and its cyclical, digital materiality for those who listen online.

The losses over time are also real and can be measured through intensity and affect. Rosemary is gone, which pains those who knew her, even as traces of her live on. Despite the repeated term ‘endlessness’, then, both Heron’s and Pountney’s End/Lessness and Beckett’s Lessness are only theoretically negentropic. The material text as given, as produced, published and read by material bodies, indeed suggests a time that inches forwards rather than repeats endlessly, backwards as forwards, through randomly generated equivalence. Instead, it is the intensity of lessness in the shadow of endlessness that is evoked: an anachromistic grey of modulating intensities. A grey on grey instance of difference is momentarily subtracted from endless grey, endless indifference, and gathered in a textual word heap. (Salisbury, 2023)

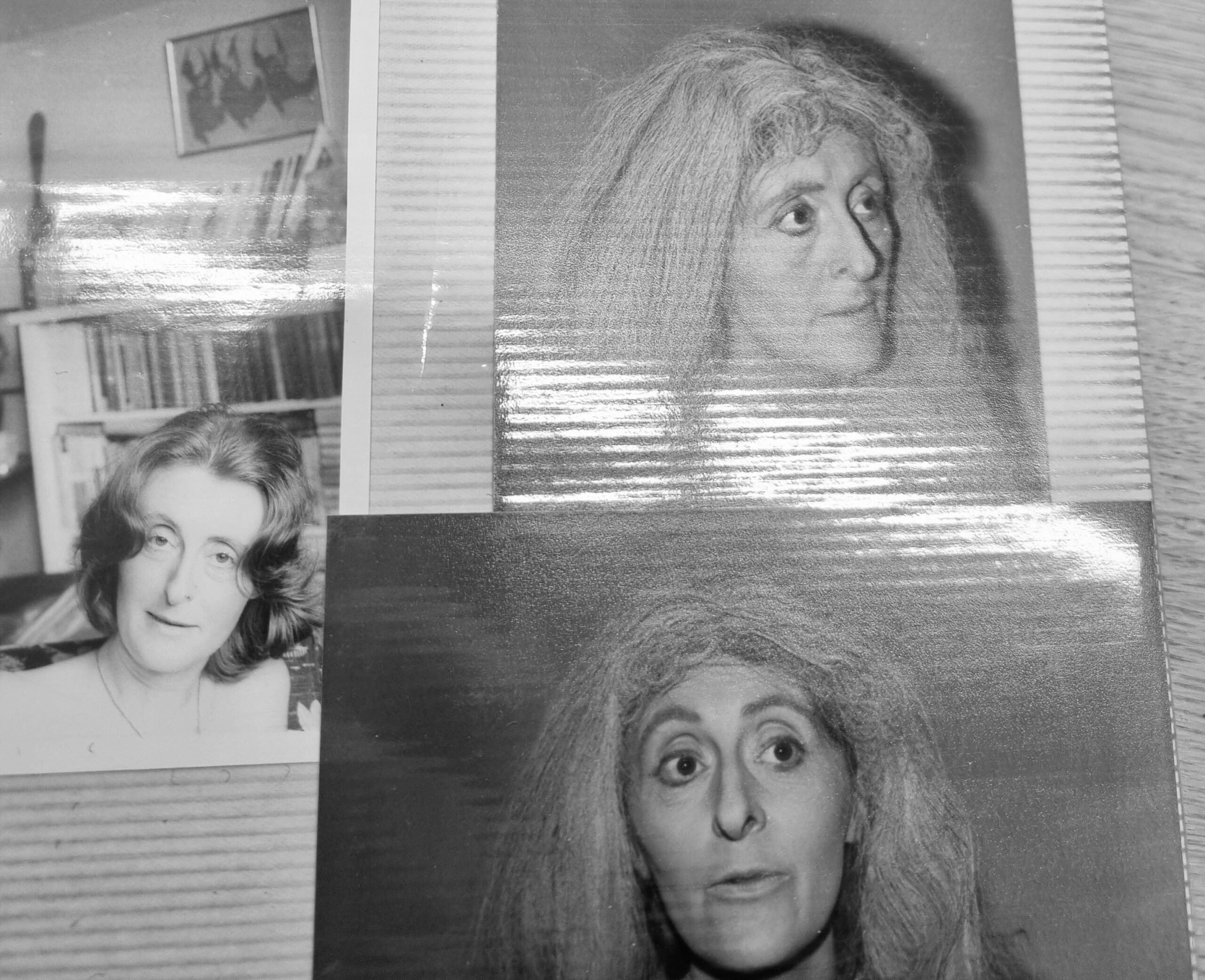

[Image 2: Production photo of Rosemary Pountney, Footfalls, 1978, image by author]

[Image 2: Production photo of Rosemary Pountney, Footfalls, 1978, image by author]

Special Collections at the University of Reading have completed a full box list of the Rosemary Pountney collection, ahead of a cataloguing process to follow. The collection is unique within Beckett studies, forming a body of work in practice and research from the 1970s to the 2010s. Her collection contains the first doctoral thesis on Beckett at the University of Oxford, submitted in 1978, which informed her monograph Theatre of Shadows (1988) alongside significant correspondence with Barbara Bray and others over many decades. Her productions of Not I, Footfalls and Rockaby are extensively documented in files, photographs and video, with a rich collection of sound media across multiple formats, covering the period 1978—2015. It is extremely rare to have one actor’s voice performing the same texts across such an extended period of theatre history and therefore there is potential for future research projects on this aspect of the archive. As Diana Taylor has shown, there is a tension ‘between the archive of supposedly enduring materials (i.e. texts, documents, buildings, bones) and the so-called ephemeral repertoire of embodied practice/knowledge (i.e. spoken language, dance, sports, ritual)’ (2003:19).

The materiality of the performance archive has been captured and celebrated elsewhere (e.g. Heron and Johnson, 2014; Johnson and Heron, 2020), but this is perhaps best documented in Rosemary’s own words (Pountney, 2014):

I first played May in Footfalls at the Dublin Theatre Festival in 1978, directed by Peter O’Shaughnessy. Rachel Burrows (one of Beckett’s Modern Language students at Trinity College Dublin) played V. In 1980 we performed the play again at Oxford Playhouse, directed by Gordon MacDougall. This production was revived in 1981 and, after performances at University College Dublin, was taken to the Beckett conference at Ohio State University, where it was performed with the world premiere of Ohio Impromptu and A Piece of Monologue with David Warrilow. Since Rachel Burrows was unable to fly to the USA for medical reasons, I had to perform May with V as a recorded voice, and it was fiendishly difficult to synchronise my replies and footsteps with the vocal cues. When in 2011 I was invited by the Norwegian National Theatre and the University of Bergen to perform Rockaby/Berceuse, a further play was required to complete the evening and I began to consider whether it might be possible to do another experimental Footfalls. A Bergen experiment would need to be far more radical than the Ohio performance, since I had developed bone problems and was unable to walk without a stick. In the original production I had been directed to pace rather like a lion in a cage. (Pountney, 2014)

[Image 3: Rosemary Pountney, Footfalls, 2012, photograph by Jennifer Schnarr]

[Image 3: Rosemary Pountney, Footfalls, 2012, photograph by Jennifer Schnarr]

The costume matters – a tangle of tatters – recalling the materiality of Beckettian productions in this first wave of work, which therefore allows for new comparative research when we consider the other collections available at Reading, especially the materials relating to Billie Whitelaw and Jocelyn Herbert as well as Katherine Worth. What is worn is important – even when it is worn out – where the embodiment of the performer co-constructs theatre histories and our understanding of the texts themselves, which brings to mind Anna McMullan’s account of the materiality of Beckettian embodiment: ‘[the body] is presented as both sign and site, engine or matrix of production (of stories, semblances, voice, footfalls or hiccups) and fabric to be composed and recomposed with limited materials’ (2010, 125, emphasis added).

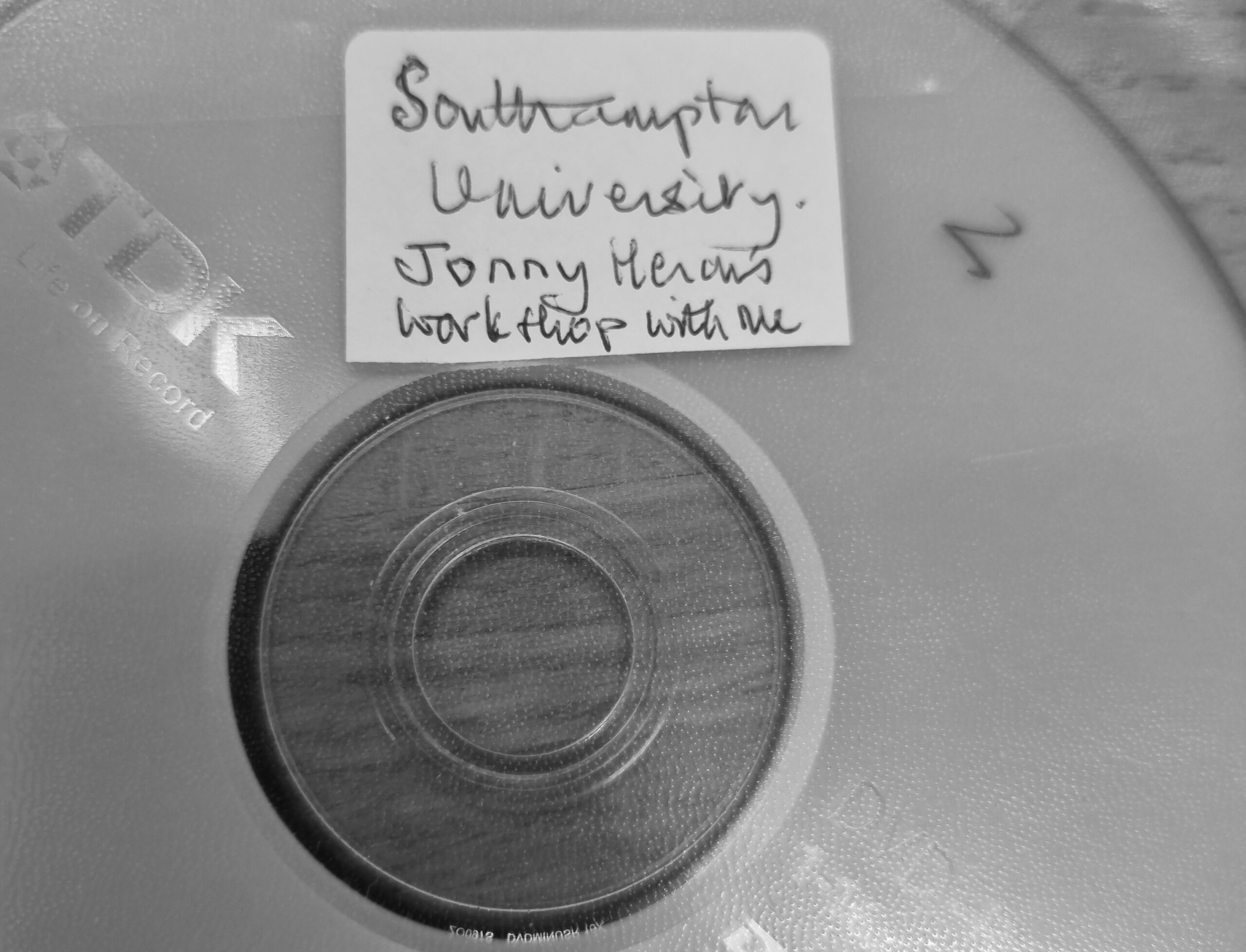

[Image 4: DVD handwritten note by Rosemary Pountney, image by author]

[Image 4: DVD handwritten note by Rosemary Pountney, image by author]

… so here I am … at the MERL in March… such a feeling buzzing between me… that sense of recognition… of self and community… the dense tangles of archival material… the box waiting patiently on the table… pencils to leave lessened traces upon items stored… so carefully curated by Rosemary herself… as she battled her illness… the box list leading me to memories of our workshops… my own writing and hers on discs and files… my illegible surname scribbled on a sticker… that time on the Solent with her and Julie… those students hearing her voice for the first time… that time on the Thames with her and Peter… and those profounds of mind… when reaching for the last file… underneath the letters to Barbara… now there’s a thing… an image floating at the bottom of the box… a card I had written towards the end… kept, collected and collated… I did not know that it was here… but there it is… the two of us in a box listed… so there we are…

[Image 5: photograph found at the bottom of the archive box, image by author]

[Image 5: photograph found at the bottom of the archive box, image by author]

For more information on the actor and scholar Rosemary Pountney, see here: https://research.reading.ac.uk/staging-beckett/interview-rosemary-pountney/

Works Cited

Coetzee, JM (1973) ‘Samuel Beckett’s Lessness: An Exercise in Decomposition’, Computers and the Humanities, Vol. 7, No. 4, pp. 195-198.

Haahr and Drew (2000) ‘Possible Lessnesses’, https://www.random.org/lessness/

Heron, Jonathan (2018) ‘End/Lessness’ in Contemporary Theatre Review: Interventions, https://www.contemporarytheatrereview.org/2018/end-lessness/

Heron, Jonathan and Johnson, Nicholas (2014) “‘First both’: Introduction to ‘the Performance Issue.’” Journal of Beckett Studies 23:1, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Johnson, Nicholas and Heron, Jonathan (2020) Experimental Beckett: Contemporary Performance Practices, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McMullan, Anna (2010) Performing Embodiment in Samuel Beckett’s Drama. London & New York: Routledge.

Pountney, Rosemary (1988), Theatre of Shadows: Samuel Beckett’s Drama 1956–76, Buckinghamshire: Colin Smythe.

Salisbury, Laura (2023) ‘Grey Time: Anachromism and Waiting for Beckett’ in Grey on Grey: At the Threshold of Philosophy and Art’ ed. Vellodi & Vinegar, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Taylor, Diana (2003), The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas, Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Beckett International Foundation Seminar – Registration

Beckett International Foundation Seminar

Minghella Studios, University of Reading, 4 November 2023

Registration for the BIF seminar on Saturday 4 November 2023 is now available here.

As in previous years, our speakers represent a mixture of early career researchers as well as established scholars, local and international, reflecting current research into Beckett’s work. We hope that the programme will, as in the past, attract a wide and varied audience.

Programme

10.30 – 11.00: Registration / Welcome

11.00 – 11.30: Xander Ryan (University of Reading): ‘From Little Jerusalem to the Paris Conservatoire: Samuel Beckett, Leslie Daiken, Melanie Daiken’

11.30 – 12.00: Discussion

12.00 – 12.15: Tea / Coffee Break

12.15 – 12.45: Velibor Topic (Actor): ‘Waiting for Godot in Sarajevo: Reflections 30 Years On’

12.45 – 1.15: Discussion

1.15 – 2.15: Lunch

2.15 – 2.45: Elizabeth Barry (University of Warwick): ‘“The Protestant Thing to Do”: Beckett, Charity and the Ambivalent Work of Social Care’

2.45 – 3.15: Discussion

3.15 – 3.30: Tea / Coffee Break

3.30 – 4.00: Hannah Simpson (University of Edinburgh): ‘Samuel Beckett and Disability Performance’

4.00 – 4.30: Discussion

To attend this year’s BIF Seminar, please register here: https://www.store.reading.ac.uk/conferences-and-events/faculty-of-arts-humanities-social-science/english-literature-department/beckett-international-foundation-research-seminar-2023

We look forward to seeing you there!

Beckett International Foundation Seminar – 4 November 2023

We are pleased to announce that the 33rd BIF Seminar will take place at the University of Reading on Saturday 4 November 2023, with the following speakers:

Elizabeth Barry (University of Warwick): ‘“The Protestant Thing to Do”: Beckett, Charity and the Ambivalent Work of Social Care’

Xander Ryan (University of Reading): ‘From Little Jerusalem to the Paris Conservatoire: Samuel Beckett, Leslie Daiken, Melanie Daiken’

Hannah Simpson (University of Edinburgh): ‘Samuel Beckett and Disability Performance’

Velibor Topic (Actor): ‘Waiting for Godot in Sarajevo: Reflections 30 Years On’

Further details re timings and how to register will be sent out later this week. Please save the date, and we hope to see you at the seminar!

Update on the Solange and Stephen Joyce Archive at the University of Reading

We write to provide news of progress about the acquisition of the Joyce archive at Special Collections, University of Reading. This progress has been somewhat hampered by delays outside of our control, beyond our previous announcements of a schedule for curating the archive and opening it for public viewing; therefore, we thought it helpful to provide this update.

Work began last year on curating and cataloguing the materials then arrived in Reading, including the correspondence and family documents and photographs. The University has also employed a qualified postdoctoral researcher to conduct an initial scoping of the materials and to input to the cataloguing process.

However, customs delays meant that the portion of the archive coming from France only arrived in Reading in late April this year. This means that we have put in place a new timetable for making the collection available to the public and launching the materials for research:

- 26th September 2023 – 2 February 2024. Small exhibition of rare books, art works and artefacts;

- Autumn 2023. Full access to published materials in the Joyce Open Access Room, a dedicated space alongside our extant Samuel Beckett Open Access collection. Rarer books will be available on request via the Reading Room;

- December 2024/January 2025. Launch event for the archival materials and letters in Reading; publication of a physical catalogue alongside the web-based catalogue, with full descriptive content. Opening of archive for researcher use;

- Summer 2026 Conference about the archive with invited speakers and CFP.

Please address any enquiries to Steven Matthews, Co-Director of the Samuel Beckett Research Centre, at s.matthews@reading.ac.uk

Screening: Samuel Beckett and Artists’ Cinema

Beckett’s work has inspired many contemporary visual artists, but in recent years it has been the area of artists’ film that has seen the clearest impact.

On Friday 23rd of June 2023, The Samuel Beckett Research Centre at the University of Reading will present rarely screened work by several artists. The screenings will be followed by a roundtable discussion and the launch of Samuel Beckett’s Afterlives: Adaptation, Remediation, Appropriation, the recent collection of essays edited by Jonathan Bignell, Anna McMullan and Pim Verhulst.

The programme for the event includes:

Introduction by Conor Carville

Stan Douglas, Vidéo (2007): Introduced by Pim Verhulst.

Stan Douglas’ video installation Vidéo is a reimagining of both Orson Welles’s film “The Trial” (based on Kafka’s novel of the same name) and Beckett’s film “Film”.

John Gerrard, Bone Work (Gulf of Mexico) (2022): Introduced by John Gerrard (Via Zoom).

John Gerrard’s Bone Work (Gulf of Mexico) is a simulation centred on sixteen fragments of dead coral found by the artist on the shores of the Yucatán Peninsula on the Gulf Of Mexico.

Duncan Campbell, o Joan, no…(2006): Introduced by Duncan Campbell.

Duncan Campbell’s o Joan, no…(2006) is a short film drawing on the lighting directions and effects in Beckett’s Play.

Roundtable Discussion on Beckett, Artists’ Film/Installation and Adaptation.

Jonathan Bignell (Reading); Pim Verhulst (Antwerp); Duncan Campbell; David Houston Jones (Exeter); Anthony Paraskeva (Roehampton); Derval Tubridy (Goldsmiths); Jivitesh Vashisht (UCD).