Silchester Environs Aerial and Lidar Survey

A detailed examination of aerial photographs and lidar imagery has been carried out as part of the desk-based assessment of the Silchester Environs Project. Aerial photographs have the potential to reveal archaeological sites that may not be apparent in a landscape possibly due to their scale, or, their lack of survival above the ground surface meaning that they can only be identified through their effects on vegetation growing above them. Lidar (Light detection and ranging) is a method of airborne laser scanning which builds up a detailed model of the ground surface. The laser can penetrate some types of tree foliage which enables archaeological sites within woodland to be identified.

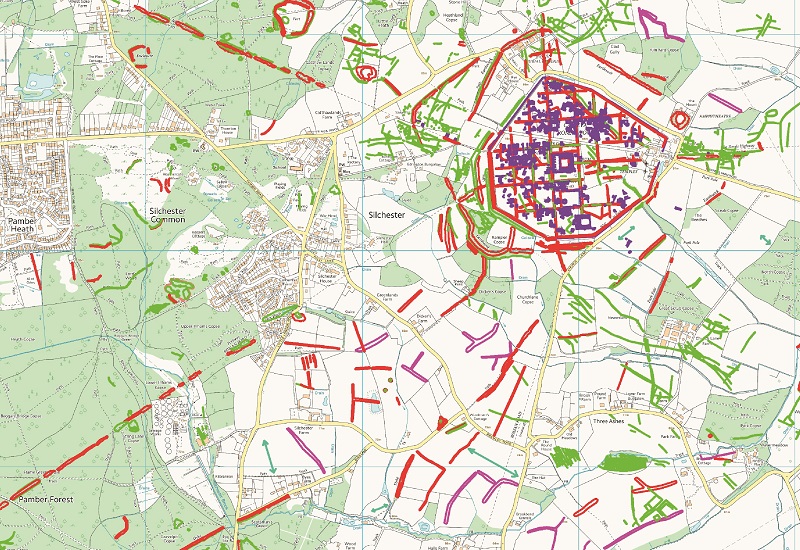

The aerial photo and lidar survey has covered 143 km², larger than the core project area of c. 100 km², in order to join the survey with previous aerial mapping projects carried out around it and put Silchester into a wider context. While the emphasis of the overall project is on the Iron Age, monuments from all periods from the Neolithic up until the Cold War have been mapped and recorded; a total of 671 new sites were discovered and information was added to 81 of the known sites in the area. Site types include prehistoric funerary monuments and settlements, medieval deer park boundaries and Second World War ordnance production and storage sites. This provides a framework for understanding how the landscape has been altered over time and how this affects our understanding and perception of the Iron Age to Roman transition.

Silchester and its earthworks

The Iron Age oppidum and later Roman and town of Calleva Atrebatum has been recorded and earlier features, possibly roads or trackways, have also been identified within it. Later field boundaries were also identified from aerial photographs and lidar which comparison with historic maps suggested might date to the medieval, or early post medieval, periods, when the interior of the town was split into communally cultivated fields.

Lidar shows clearly that the oppidum may incorporate an earlier enclosure at Rampier Copse in the south-western corner of the outer defensive earthwork. A curving bank extends from the outer earthwork to meet the town walls.

A system of linear dykes are found around Silchester which may have had an association with either the oppidum or, possibly, earlier Iron Age settlement. They may delineate individual areas of land or control access or movement of people in some way, or be a more symbolic form of territorial boundary marker. They are found at varying distances from the Late Iron Age settlement, either leading away from it or on different orientations. They extend to the south and west and to the north-east from Calleva and, in the case of Grim’s Bank, run from south-west to north-east at some distance from the oppidum but following a similar alignment to the earthworks closer to the settlement. The total area covered by the oppidum and dykes around it is approximately 129 hectares.

The dykes around Calleva may not all be of one design or purpose, but they do constitute distinct markers in the landscape. It is unclear whether they are delineating separate types of settlement, or controlling movement within a specified territory. What can be seen now is probably a small proportion of the original earthworks, but their alignments persist in the landscape in a way that cannot be seen for the majority of the Roman roads. The surviving sections identified as earthworks or cropmarks often sit between extant trackways, roads and field boundaries, which suggest that the dykes may once have been more extensive features.

The survey has identified an interesting pattern of Later Prehistoric to Roman settlement around the town. Probable later prehistoric settlement sites, often consisting of circular or oval enclosures, have been identified as surviving earthworks within woodland and as cropmarks within farmland.

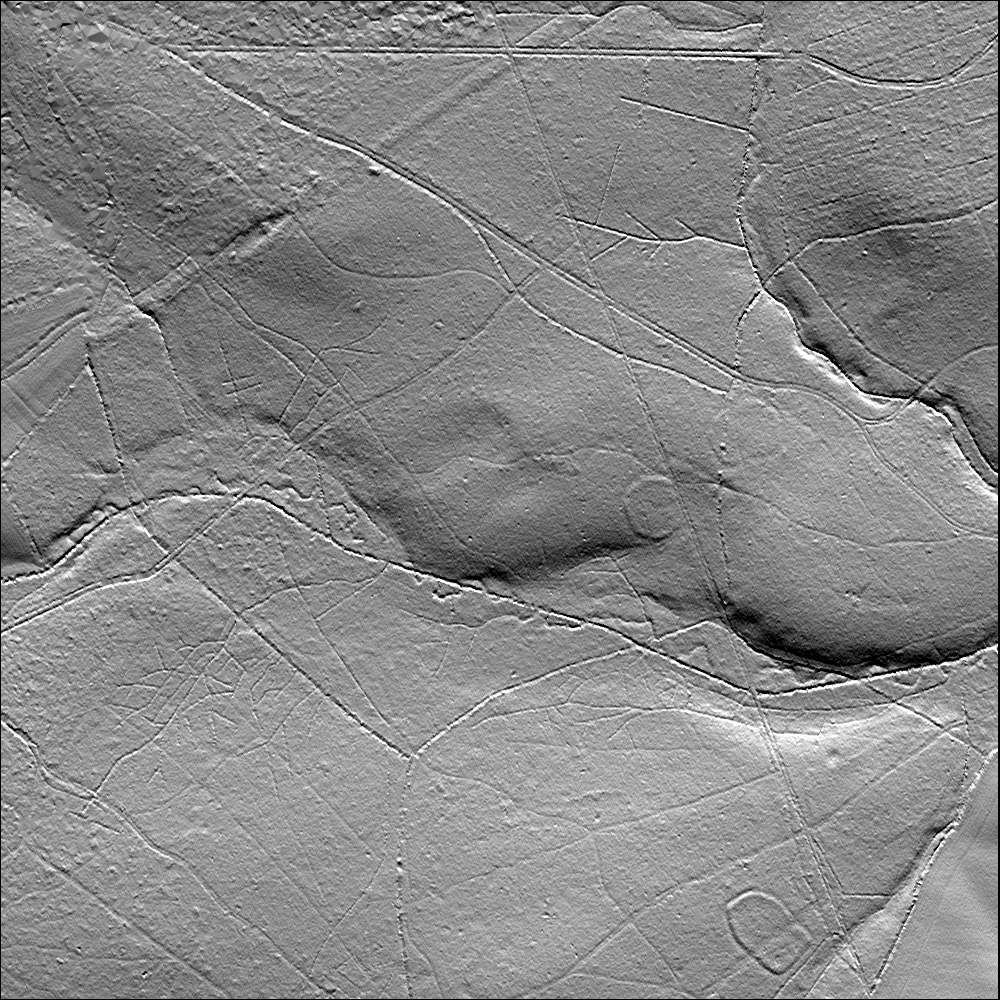

Four enclosures, which may date to the Bronze Age and Iron Age, were identified through the survey as extant earthworks on lidar coverage of Pamber Forest. The forest, though now reduced in size, has been in existence since at least the time of the Domesday Survey and it was designated as a Royal hunting forest. It is possible that this different status and land use protected the enclosures within it, which probably survive from a period when the land was more open. Two of the enclosures (1 and 2 on the lidar hillshade image) are located in the northern part of the forest and may be Later Bronze Age or Iron Age in date. A sub-rectangular enclosure in the south of the forest (3 on the lidar image) adjacent to a possible Bronze Age round barrow, newly identified through the lidar survey. It is a more substantial earthwork with a well-defined bank with an external ditch. The fourth enclosure in Gold Oak Copse is smaller in size and appears to have been damaged by a later network of trackways.

As a result of this survey, excavation has been carried out on enclosures 1, 2 and 3 (March 2017) by the Silchester Environs project team. Preliminary results suggest that the pair of enclosures (1 and 2) may be Bronze Age in date and that the larger enclosure (3) is probably Iron Age. Pottery from enclosure 3 is yet to be dated, but, by form and appearance, is Iron Age in date. The paired enclosures may have originated in the Late Bronze Age. If these are farming settlements, there is no evidence that can be identified on the lidar coverage of field systems associated with them. Field boundaries might be expected to be preserved as earthworks within the forest given the clear appearance of the enclosures but may be too slight as features to be identified by the available lidar (1 m resolution Environment Agency). It is possible that their location on clay soils meant that they specialised in livestock rather than arable farming.

Settlements of Iron Age to Roman date have also been identified from cropmarks on aerial photographs, either as single, rectangular, ditched enclosures, or as multiple enclosures in a ladder pattern. The majority of these settlements were identified on areas of soil overlying gravels, but a new site, consisting of multiple enclosures, was discovered from cropmarks unusually seen on clay soils to the west of Little London.

To add to this picture of changing social structures and patterns of settlement, the remains of what may be a villa complex or settlement have been recorded from cropmarks to the south of Calleva in Nelson’s Field. A group of enclosures were recorded as earthworks from lidar imagery within Bramley Frith Wood to the south of Nelson’s Field which appear to end at the parish boundary on their northern side. This leaves an intriguing gap between the two sets of features where nothing could be identified from either aerial imagery or lidar.

Little evidence has been found so far of the field systems that would have accompanied these settlement sites, but fragments have been recorded in several locations around Silchester. Cropmarks can be seen on 1930s aerial photographs (collected by OGS Crawford) to the north of Calleva, but they appear to have been completely removed after this time. Recent geophysical survey produced no results for this area and the field boundaries cannot be seen on later photographs. The fact that they could be recorded at all demonstrates the value of a systematic survey of historic aerial photography. It also indicates that, while the landscape use may be relatively static today, it has seen the effects of agricultural intensification in the past, probably in the post-Second World War period.

Visibility of Archaeological Features

The geology of the Silchester area has a great effect on the appearance of archaeological sites on aerial photographs and lidar imagery. The Silchester area itself sits on a gravel plateau which, with its free draining soils, is conducive to cropmark formation. The landscape around it to the north, east and south is predominantly London Clay and the appearance of cropmarks on these heavy soils is, while not unknown, relatively rare. The predominance of London Clay in this area also has an effect on the type of archaeology found. Sites associated with drainage and water management, such as water meadows, homestead moats and brickworks are common across the project area. Brickworks continue into at least the 19th century and Brickearth pits have been recorded as surviving earthworks from lidar. Exploitation of the clay has a long history in this area. For example, Roman kiln sites have been identified through geophysical survey and excavation around Calleva.

Later use of the landscape has probably also greatly affected the appearance of archaeology in this area. Large areas have been turned over to military use from the First World War onwards and many continue to be Ministry of Defence sites, such as the Second World War Aldermaston airfield which is now the Atomic Weapons Establishment. The area was a focus for ordnance production and storage: the Burghfield Ordnance Filling Factory was located in the northern part of the survey area and the First and Second World War ordnance depot at Bramley Camp in the southern area. Numerous, extensive, areas of dispersed munitions storage were located within the country parks and woodland around Bramley Camp. Other features were more transitory in nature, including: a Prisoner of War Camp at Stratfield Mortimer; e; and Heavy Anti-Aircraft batteries.

The results of this survey are enabling the team to identify sites which warrant further investigation, by geophysical survey, use of historical records and in some cases coring or excavation, the latter to enable dating and study of the artefacts and ecofacts which can tell us about the use and chronology of the sites and their relationship to others in the wider landscape.