Many visitors to Glastonbury Abbey today expect to see a visible monument to King Arthur, commemorating the popular belief that he was buried at Glastonbury in the 6th century. In 1191, the monks uncovered two skeletons that they claimed were those of King Arthur and his second queen, Guinevere. They placed the bones in a tomb chest in front of the high altar of the great church, the place of highest honour, and a royal cult around Arthur was born.

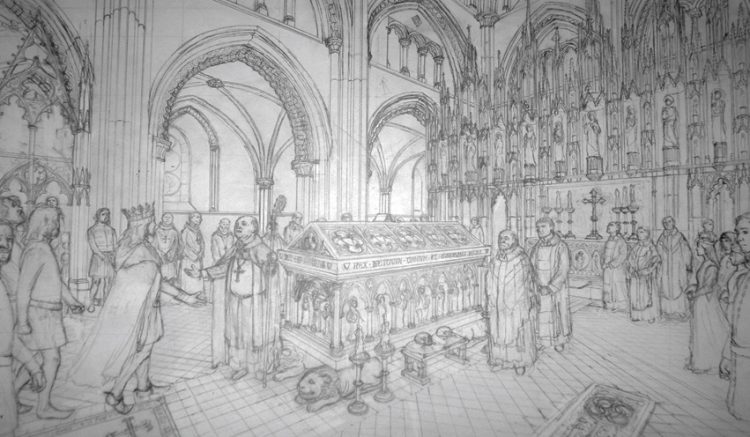

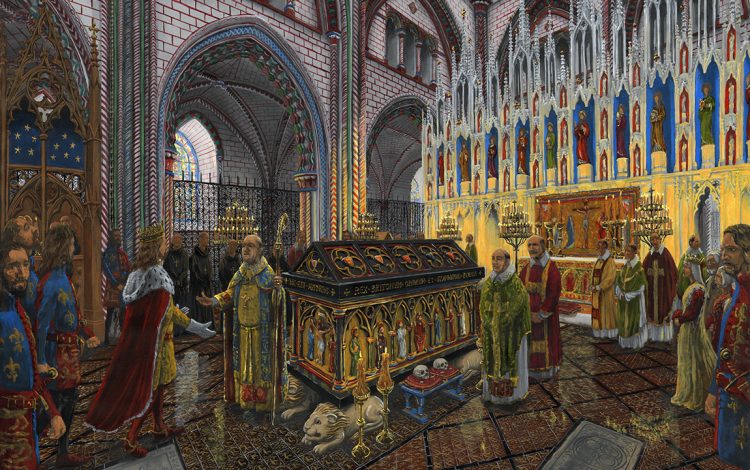

Arthur has been associated with Glastonbury Abbey for over 800 years but today there are no physical remains of his tomb. A reconstruction of the tomb was therefore a high priority for the abbey, to help visitors to understand what Arthur’s tomb may have looked like and how it related to the spaces of the medieval church. We took the decision to represent Arthur’s tomb through the medium of a traditional artist’s drawing (by Dominic Andrews), rather than a digital reconstruction. Particular care is needed when reconstructing objects associated with legends – there is a risk that digital reconstructions may be perceived as somehow more ‘real’ than an artist’s reconstruction.

The reconstruction drawing is based on archaeological evidence for the layout of the great church and a detailed description of the tomb by the antiquary John Leland in the 1530s. Leland described a tomb of black marble with four lions at its base, a crucifix at the head and an image of Arthur carved in relief at the foot. The style Leland described is very similar to Roman tomb chests and this archaic style may have been chosen to emphasise the antiquity of King Arthur.

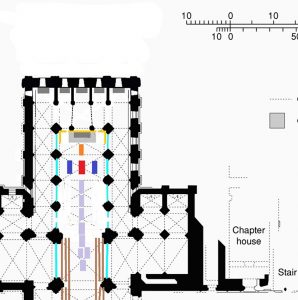

Dominic began by making a plan of the church based on excavated evidence and historical sources, to work out exactly where Arthur’s tomb was sited and how the choir, the area around it, was arranged.

The next step was to reconstruct the interior of the choir, the eastern part of the church which accommodated the monks during liturgy, and where Arthur’s tomb was also located. We had a long debate on whether the entrance to the eastern end of the church should be shown as having two or three arches leading to chapels – the archaeological evidence suggests two, but three would be more in keeping with the aesthetics of Gothic architecture. This turned out to be a moot point – as the reredos, a decorative screen above and behind the high altar, blocks this view in the final reconstruction!

We chose to depict a visit to Arthur’s tomb by King Edward III and Queen Philippa in December, 1331. This is a well-documented occasion when a high status woman was at the centre of action in the male monastic community. The king is shown being greeted by the abbot, while the queen (who had arrived earlier) waits to one side. The skulls and knee bones of Arthur and Guinevere are laid out for devotion on velvet cushions for inspection.

The tomb takes pride of place before a painted altar and reredos, surrounded by richly robed clergy and royal retainers. Archaeological evidence from Glastonbury suggests the colour palette and details of wall-painting and floor-tiles. Additional furnishings shown in the reconstruction are modelled on examples surviving from elsewhere, such as the iron screen (based on the Chichester Grille, now in the V&A), while the reredos is based on architectural details from Glastonbury and contemporary sites including Winchester and Wells.

Building on the brief information in Leland’s description, we used marble tomb-chests which survive in Cordoba (Spain) as a guide to what the tomb may have looked like. In particular, the positioning of the prominent lions as ‘feet’ facing outwards at either end. We also drew on the architecture and style of Henry of Blois’ own tomb in Winchester, as Henry was so closely connected with Glastonbury and its history. All these have lost their original paint, so the colour scheme is conjectural, but we do know that medieval tombs were brightly painted and gilded and studded with both real and paste jewels.

Roberta Gilchrist is Professor of Archaeology and Research Dean at the University of Reading. She has worked with Glastonbury Abbey since 2006, is a Trustee of the Abbey, and led both the ‘Glastonbury Abbey Archaeological Archive Project’ and ‘Glastonbury Abbey: archaeology, legend and public engagement’. She has published pioneering works on medieval nunneries (1994), hospitals (1995), burial practices (2005) and popular devotion (2012), as well as major studies on Glastonbury Abbey (2015) and Norwich Cathedral Close (2005). She is an elected Fellow of the British Academy and was voted Current Archaeology’s ‘Archaeologist of the Year 2016’.

Roberta Gilchrist is Professor of Archaeology and Research Dean at the University of Reading. She has worked with Glastonbury Abbey since 2006, is a Trustee of the Abbey, and led both the ‘Glastonbury Abbey Archaeological Archive Project’ and ‘Glastonbury Abbey: archaeology, legend and public engagement’. She has published pioneering works on medieval nunneries (1994), hospitals (1995), burial practices (2005) and popular devotion (2012), as well as major studies on Glastonbury Abbey (2015) and Norwich Cathedral Close (2005). She is an elected Fellow of the British Academy and was voted Current Archaeology’s ‘Archaeologist of the Year 2016’.