Abbey after the Reformation

Huguenots

Following the Dissolution and the seizure of the abbey and its estates, many of the buildings were dismantled and the materials reused. In 1547, the site of the former abbey was granted to Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset and royal favourite. He paid for Protestant refugees known as Huguenots to come from Flanders (Belgium) to establish a centre of the weaving industry at Glastonbury. Huguenots were famed for their skill in silk weaving and their work was highly prized across Europe.

They built houses within the precinct and their leader occupied the former abbot’s lodging. By 1552, there were 29 houses and 44 families, forming a thriving industrial community. However, when the Catholic Queen Mary was crowned in 1553, the Huguenot weavers were forced to flee, fearing religious persecution. They fled to Frankfurt never to return.

Why the Lady Chapel survived

After the Dissolution, stone and timber from the monastic buildings was taken for reuse (any valuable lead was claimed by the crown). The Lady Chapel survived, showing its ongoing importance to the local community.

By 1520, the former Lady Chapel was known as St Joseph’s Chapel, the dedication of the chapel in the crypt. It was a powerful symbol of the abbey’s ancient origins and its link to Joseph of Arimathea, who had reputedly built the first chapel on the site.

The legends surrounding the chapel became important to the emerging Protestant nation. Queen Elizabeth I used Glastonbury’s origin story, and its connections with Joseph (and reputedly Christ himself), to assert the independence of the English Church from Rome.

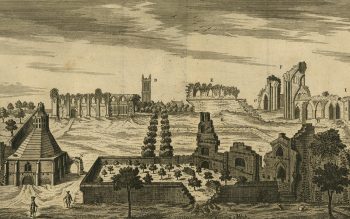

Stukeley drawings

By the early 18th century, there was a growing interest in the investigation of the past. The famous antiquary William Stukeley visited the site of the former abbey in 1723. His drawings give us a good idea of the layout of the site and the style of the buildings which remained 300 years ago.

He drew the ruins of the church and Lady Chapel and the abbot’s complex. He showed the second abbot’s hall that had been added in the 15th century. We know from the abbey’s records that it was extended in 1497 for a visit by King Henry VII: he spent one night as the guest of Abbot Beere.