Archaeology of Food and Drink

Ceramics

The abbot’s hall was a grand ceremonial space designed for entertaining on an impressive scale. The last abbot of Glastonbury entertained up to 500 “persons of fashion” in the hall at one time. They would have eaten the finest food that the abbey’s estates could offer and preparations would have required the work of hundreds of servants. Meals typically included birds, fish, meat from the estates, as well as sweetmeats cooked with expensive and exotic spices.

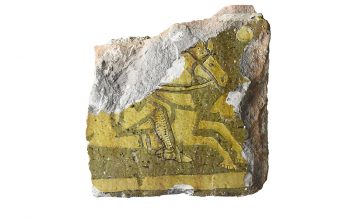

Archaeological excavations in this area found large numbers of pottery jugs for serving wine and ale. Although wine was made in England (including at Glastonbury), the finest wines were imported from France and the abbot’s guests would have enjoyed these as well as local ale. They dined in beautiful surroundings: the floor was paved with ceramic tiles and the windows were glazed with high quality glass.

Animal and fish bone

Fragments of animal and fish bone excavated from Glastonbury Abbey reflect a typical monastic diet. The Rule of St Benedict allowed fish and poultry to be eaten but red meat was forbidden to all except the sick.

Large numbers of fish bone were found in the floor deposits of the abbot’s kitchen. The church required fish to be eaten on specific days each week and at certain times in the year. Fish was provided by the abbey’s fishery at Meare, although much fish was salted or dried for winter use.

Excavated bones from across the site include many birds, including wildfowl and waterfowl like snipe and ducks, but also young pig and sheep. This suggests that the strict dietary rules were relaxed in the later middle ages, especially for the abbot and his guests, but possibly for the monks as well.

Abbot’s Kitchen

Glastonbury’s famous kitchen shows the lavish scale of the abbot’s complex. This kitchen was for the use of the abbot’s staff alone; there was a similar one built to cook the monks’ food.

This unusual building has a vaulted octagonal roof and lantern which released heat as well as providing natural light. The central space contained four fireplaces, one of which was a pastry oven. Historical documents and close study of the surviving building by Jerry Sampson show that it was constructed around 1330 at the time that the abbot’s complex was being rebuilt.

Excavations within the abbot’s kitchen revealed evidence for an even earlier phase. Floor deposits have been radiocarbon dated to around 1250, showing there was an earlier kitchen on the same site.