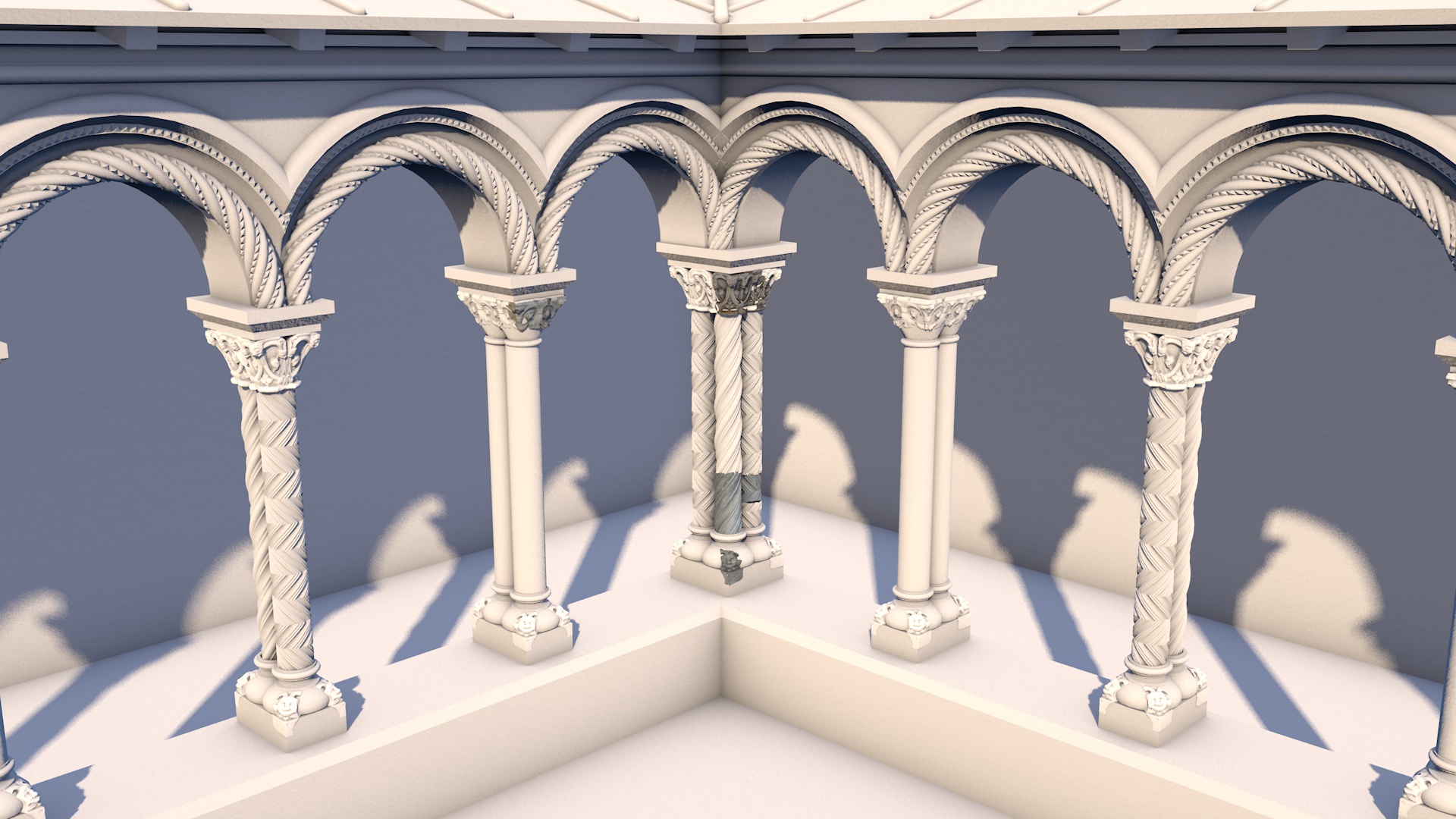

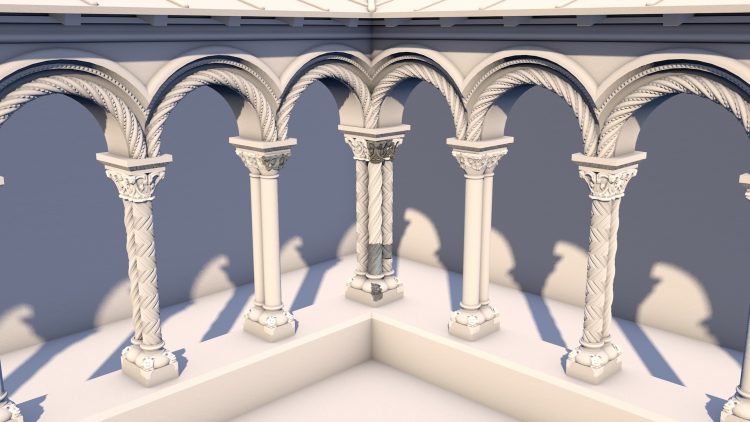

Among the treasure-trove of architectural fragments at the abbey is a collection of finely-carved blue-lias fragments which have long been regarded as part of Henry of Blois’ magnificent 12th-century cloister. The form of the cloister is a matter for speculation, but a handful of the cloister fragments provides enough useful information to make an attempt at imagining Henry’s cloister. Our model is one vision of how the cloister could have appeared in c.1150, but it is simply one interpretation. The process of digitally reconstructing the cloister has suggested a slightly different interpretation from that published by Ron Baxter in the 2015 monograph on Glastonbury Abbey. Here we show the cloister arcade with double-shafts throughout, whereas Baxter suggested that it is likely to have had alternating single and double shafts.

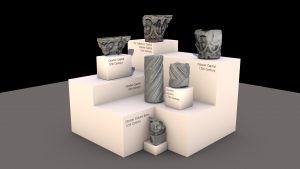

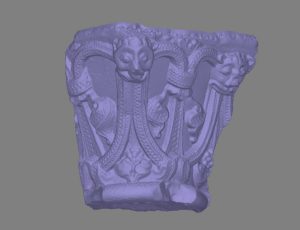

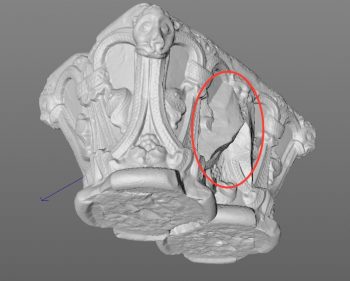

Our reconstruction is based on six fragments now displayed in the abbey museum. These are a portion of a column base (the famous lion sculpture), two fragments of decorated column shafts, and three pieces from column capitals. All of these are not only beautiful, but particularly important to our reconstruction because they retain details which help us determine the measurements and proportions of the bases, shafts, and capitals when they were whole. The capitals are particularly important because it is clear that at least one of them is a special kind of capital – a double-capital which looked like two capitals carved side-by-side from a single stone – which is a kind specifically used in cloisters in Britain and Europe between the 11th and 13th centuries.

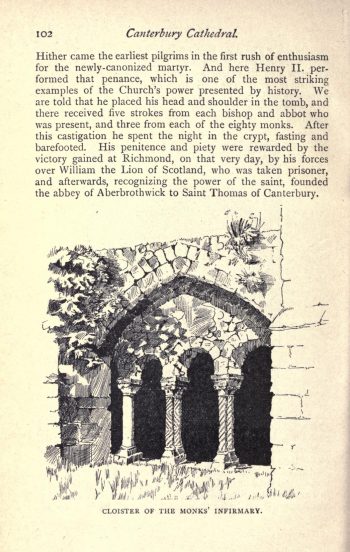

It seems very likely that Henry’s cloister was composed of arcades of round-headed arches resting on slender pairs of highly decorated pillars. One of the best surviving examples of this type of cloister arcade from this period still stands in the Infirmary at Canterbury Cathedral (see the illustration, left). There, the arcade is composed of alternating double and single-shafts. It is possible that a similar pattern of shafts existed at Glastonbury too, but none of the surviving fragments retain enough detail to be absolutely certain. There is one piece of a column shaft from the set of cloister fragments which is from a column that was slightly fatter than the others, but this is the only evidence which hints at a singe-double-shaft pattern that survives and it is entirely possible that this single fragment is not a part of the cloister arcade at all. The weight of the evidence, such as it is, suggests double-shafts throughout.

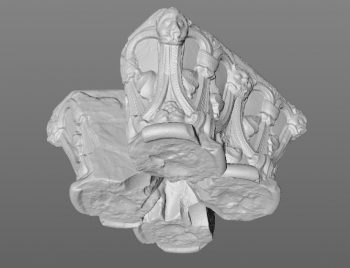

In the process of creating our cloister reconstruction we made several discoveries which helped us to better understand the surviving fragments. Modelling Henry’s cloister began with a photogrammetric survey of the six key fragments in the museum. Photogrammetry is a way of capturing real-world objects in highly-detailed 3D using a set of photographs and specialist software. These models allow us to test our ideas about how the cloister looked in 3D. For example, the beautiful ‘Salisbury Capital’ has been thought to be one half of a double-capital. However, when we duplicated our model of the capital and ‘mirrored’ it to provide the missing half the broken ‘back’ of the fragment poked through the carved ‘face’. The Salisbury capital was too large to be a free-standing double-capital of the kind common to cloisters of this period. Instead, it is either part of a double-capital that was fixed to a wall, or, perhaps more interestingly, it may have formed part of a quadruple-capital for four columns bundled at the corners of the cloisters. This is what we showed in our reconstruction.

Photogrammetry also helped us better understand the other two capital fragments as well. The large fragment that resembles the Salisbury Capital must be part of a double-capital. When we reconstructed its missing sides we found that the broken portions are too large to fit within the volume of a single-capital which suggests that half of it is missing. The final fragment, with different ornamental details, provides less to go on. It could have been the short end of another double-capital, or it could have been one side of a single-capital. If it was a single capital, the shaft it would have capped would have been the same diameter as the two ornate pieces in the museum. If the cloister arcade alternated between double and single columns, we assumed that the single columns would be much ‘fatter’ than the double columns, as they are at Canterbury. It seems unlikely, and perhaps structurally unsound, to alternate between double and single columns all of the same, or nearly same, diameters. Therefore, we chose to represent this capital fragment as a portion of a double-capital in our reconstruction.

The other elements of the model are far more speculative in nature. We chose to alternate groups of ornate and plain column shafts to add more visual variety. The very ornate arch heads are inspired by those of continental cloisters of the period, particularly the intact ones at Moissac, France. In England, richly carved cloister arcade arches also survive as fragments at Reading Abbey and Bridlington Priory. For the width of the cloisters we relied on evidence from the below-ground archaeology.

The height of the cloisters and the width of the individual arches are more difficult to determine. The great fire of 1184 destroyed many abbey buildings, and we are not sure to what extent the cloisters were affected. Building work in the cloister certainly occurred after the fire, but whether this was a complete rebuild or just repairs and updating of Henry’s (largely surviving) pre-fire cloister is unclear. If the latter, then the original cloister’s proportions would likely be retained. Acknowledging this uncertainty, we have had to use the evidence available to us: fortunately, the proportions of the post-fire cloisters are preserved in scars running along the south wall of the abbey church ruins.

No reconstruction effort can be anything other than a plausible argument and educated conjecture. Henry of Blois’ original cloister is forever lost. However, the pieces that do survive provide a tantalizing glimpse of a fascinating past. The clues these pieces present stir the imagination and invite attempts – even though they must remain speculative – to reconstruct their former glory.

View the full reconstruction below, and visit the pages in the ‘Digital’ section of this website, The Cloister (c.1150s), for more information.

Anthony Masinton is a 3D visualization specialist. He has a BA in English and Anthropology from the University of Denver and an MA in Medieval Archaeology from Durham University. He holds a PhD in Medieval Studies from the Centre for Medieval Studies, University of York. His doctoral work studied the late medieval relationship between God and man in English parish churches. Anthony helped construct the 3D visualizations of Glastonbury Abbey for inclusion in the on-site interpretative media and the Glastonbury Abbey Archaeology website.

Anthony Masinton is a 3D visualization specialist. He has a BA in English and Anthropology from the University of Denver and an MA in Medieval Archaeology from Durham University. He holds a PhD in Medieval Studies from the Centre for Medieval Studies, University of York. His doctoral work studied the late medieval relationship between God and man in English parish churches. Anthony helped construct the 3D visualizations of Glastonbury Abbey for inclusion in the on-site interpretative media and the Glastonbury Abbey Archaeology website.