When creating 3D visualisations of lost buildings we must use all the evidence available to help us define what these structures looked like (read our post on recreating lost buildings for more on this). However, the evidence can often be contradictory… or perhaps not even exist at all for certain elements. In these cases, the process of building something digitally in 3D space can sometimes offer important insight where other forms of knowledge are absent.

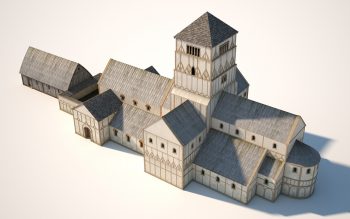

A good example is the question of whether the Anglo-Saxon church, which preceded the larger medieval abbey at Glastonbury, had a specific architectural feature known as an apse. An apse is an adjoining structure at the east end of a church’s chancel, which is often (but not exclusively) semi-circular in plan. They were the most sacred places within a church, and usually housed the high altar and important relics associated with the church or its religious order.

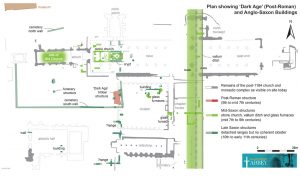

When the churches were excavated in the 1920s, the archaeologists interpreted the plan of the earliest church as terminating in an eastern apse. The evidence was not clear but because many other churches of this period across the country had apses it was considered a likelihood. But when we began work on reconstructing the first phase, we encountered a curious problem: there does not seem to have been space for the apse in this phase!

The first stone-built Anglo-Saxon church at Glastonbury (see 700 AD image above) sat alongside two other buildings: the ‘Old Church’ (which was already in existence prior to this phase of building) to the immediate west, and a mausoleum/crypt to the immediate east. The plans drawn up by archaeological work in the 1920s indicated a position for the mausoleum, which was accessed via a doorway and steps at its west end, that was simply too close to the assumed apse: roughly 1 metre – certainly too small a space to manoeuvre a body into the doorway and down the stairs. The following video provides an animated explanation of the issue.

How can we account for this discrepancy? It is possible that the archaeological plans were incorrect, but the most likely explanation is simply that the earliest Anglo-Saxon church did not have an apse. Was this omission a conscious decision on the part of the builders because they knew they did not have space? Or perhaps an apse for this initial phase of building was never considered in the first place. Through 3D visualization we can explore questions of a physical nature that are sometimes invisible through other media. The process of digitally reconstructing the first phase church has challenged previous interpretations of the evidence.

Patrick Gibbs is Head of Technical Design at the Centre for the Study of Christianity and Culture, a research centre based at the University of York. He specialises in the creation of digital interpretation for historic sites and visitor attractions via interactive touchscreens, mobile device media and online web resources. Patrick helped design and create interactive digital media for Glastonbury Abbey, and helped construct the Glastonbury Abbey Archaeology website.

Patrick Gibbs is Head of Technical Design at the Centre for the Study of Christianity and Culture, a research centre based at the University of York. He specialises in the creation of digital interpretation for historic sites and visitor attractions via interactive touchscreens, mobile device media and online web resources. Patrick helped design and create interactive digital media for Glastonbury Abbey, and helped construct the Glastonbury Abbey Archaeology website.