The church at Glastonbury Abbey, the ruins of which we see today, was not the first religious building on this site. In fact, it was probably not even the second or third! It actually represents the last of many phases of building that grew steadily larger and more ornate over time. It is thought that an early brushwood church was built here – the legendary ‘Old Church’ – which would have stood for centuries before a fire destroyed it in 1184 (see our post on Glastonbury’s ‘Old Church’: representing ‘the cradle of English Christianity’).

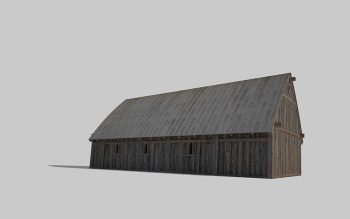

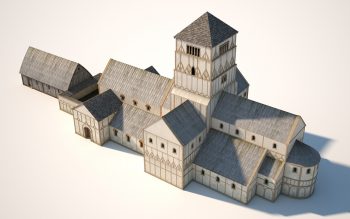

In roughly 700 AD a new stone-built church was erected to the east of the ‘Old Church’, in roughly the same location as the later medieval abbey’s nave. This may have looked similar to other surviving churches of this period, such as St Peter-on-the-Wall in Essex (see image above), and it represents the first of what we know as the ‘Anglo-Saxon churches’ at Glastonbury. This stone church was rebuilt and expanded at least twice over the next 400 years, and eventually made way for the much larger medieval abbey.

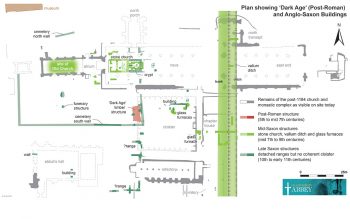

We know more about the Anglo-Saxon churches that followed than we do about the ‘Old Church’, largely thanks to archaeologists. The first excavations were undertaken in the 1920s, and these found the remnants of walls that belonged to these early buildings. However, these were only surviving portions – the full extent and form of these buildings had been lost to the later developments.

As part of this project, we felt it important to digitally visualize the earlier churches in addition to the later medieval abbey. These phases of development are an important part of the Glastonbury Abbey story, and represent a fascinating insight into early religion and architecture. But how do we go about visualizing something that is no longer there? The first step is to gather together all the available evidence. In this case, this meant archaeological reports (including those from the 1920s), academic literature on the subject, artistic representations and contemporary/historic accounts.

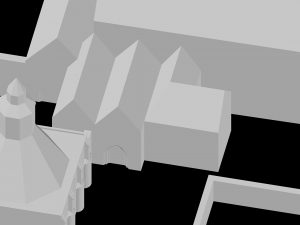

Importantly, we also looked at comparanda – buildings of a similar age, from both here in Britain and on continental Europe, that likely shared aspects of style and appearance. Through careful analysis of these diverse sources of evidence, we can begin identifying the key elements of how a structure looked… and then start on building a virtual 3D model. We use computer software commonly used in fields such as architecture and TV/film to undertake this work. The first step is usually to define the rough footprint of the building and ensure it is correctly scaled. Following that, we can build upwards to define the geometry of the building’s walls and roof. Windows, doors and other smaller features complete the geometric stage, after which we will look at adding realistic textures and colours to the visible surfaces. Finally, the 3D model can be lit using a virtual ‘sun’ to generate shadows and highlights for an added touch of realism.

The process is very ‘reflexive’: the act of creating the model itself often feeds back useful information about what does and doesn’t work, which we then use to make the final result even better. We often make mistakes, or some evidence just doesn’t fit once we start building things in digital 3D space (a good example of the latter is the question of whether the Anglo-Saxon church had a common architectural feature known as an apse – read our post on this).

However, these issues make us better informed, and helps create a more accurate, authentic visualization.

Along the way, we have help from academic advisors – scholars whose knowledge helps us identify areas that are contentious, or interpretations that are perhaps more or less likely as the visualizations develop. The final product is therefore the culmination of much research, revision and advice (see the images below). We can never know whether they are truly accurate, but they represent the most authentic interpretations to the best of our knowledge. You are of course free to disagree, which is the fascinating thing about archaeology!

Patrick Gibbs is Head of Technical Design at the Centre for the Study of Christianity and Culture, a research centre based at the University of York. He specialises in the creation of digital interpretation for historic sites and visitor attractions via interactive touchscreens, mobile device media and online web resources. Patrick helped design and create interactive digital media for Glastonbury Abbey, and helped construct the Glastonbury Abbey Archaeology website.

Patrick Gibbs is Head of Technical Design at the Centre for the Study of Christianity and Culture, a research centre based at the University of York. He specialises in the creation of digital interpretation for historic sites and visitor attractions via interactive touchscreens, mobile device media and online web resources. Patrick helped design and create interactive digital media for Glastonbury Abbey, and helped construct the Glastonbury Abbey Archaeology website.